Fort York – Toronto’s Almost Hidden Past

Over the past fifty years I have visited Toronto well over a hundred times and yet, until a few days ago, I had never ventured to Fort York where the foundations for this largest of Canadian cities were laid over 200 years ago. The site of one of the most famous battles of the War of 1812 lies almost forgotten on a triangle of land that is wedged between the city’s huge railyards and the Gardiner Expressway. It is miraculous that it managed to survive almost intact in a city that once seemed hell bent on forgetting its past. Here’s why it’s worth taking the trouble to find it and spend a few hours exploring this most interesting place.

This is an aerial photo of Fort York as it looks today. Literally hundreds of thousands of commuters whiz by it each day on Go trains or on the Gardiner Expressway, many without even knowing that the most important historical site in the city is only a stone’s throw away. I know that in dozens of rides to and from Pearson airport I never knew we were passing over a portion of Fort York; my assumption was that it was located somewhere down by the waterfront. What I didn’t know was that when it was built, it was on the shore of Lake Ontario which through centuries of landfills, is now hundreds of yards away.

Fort York is a National Historic Site, but unlike most of the others I have visited over the years, this one is not administered by Parks Canada, but rather the city of Toronto. In fact, Parks Canada oversees only 171 of Canada’s 970 National Historic Sites. As the late, great Johnny Carson used to say, “I did not know that.” until I did the research for this post.

Fort Rouillé aka Fort Toronto

Fort York was not the first European attempt to set up shop in what is now Toronto. The French tried twice. First in 1720 with a fur trading post at the mouth of the Humber River which lasted about a decade and then from 1750-59 with a small defensive establishment on the site of the Canadian National Exhibition grounds officially known as Fort Rouillé, but more commonly called Fort Toronto for the first effort at fort building in 1750. Toronto was the name various Indigenous peoples had used for the area for centuries and according to the information given at the Fort York site means ‘place where the trees stand in the water’, and I’ve you been out to the Toronto Islands, this makes sense. However, other meanings for Toronto include ‘plenty’ and ‘narrows’ so who knows the real answer to this conundrum where different tribes gave different meanings to words that sounded identical to European ears. Maybe it really means ‘Land of the blue leafs’ which would explain a lot about a certain team name and colours.

Fort Rouillé got caught up in the Seven Year’s War between France and England and after the French lost nearby Fort Niagara in 1759, they burnt the place down and withdrew to Montreal, never to return.

Establishment of Fort York

John Graves Simcoe is a towering figure in Ontario history. After the American Revolution there was a huge influx of Loyalists into the fertile lands of southern Ontario which was then called Upper Canada. Simcoe was the first Governor-General of the colony and established the settlement of York in 1793 as the seat of government as well as building a modest fort on the site. Most people consider this to be the foundation date of the city that was later renamed Toronto. As tensions with the United States escalated, another Canadian icon, Isaac Brock built a proper fort with barracks for a sizeable garrison and a powder magazine that was to play an important role in what was to come.

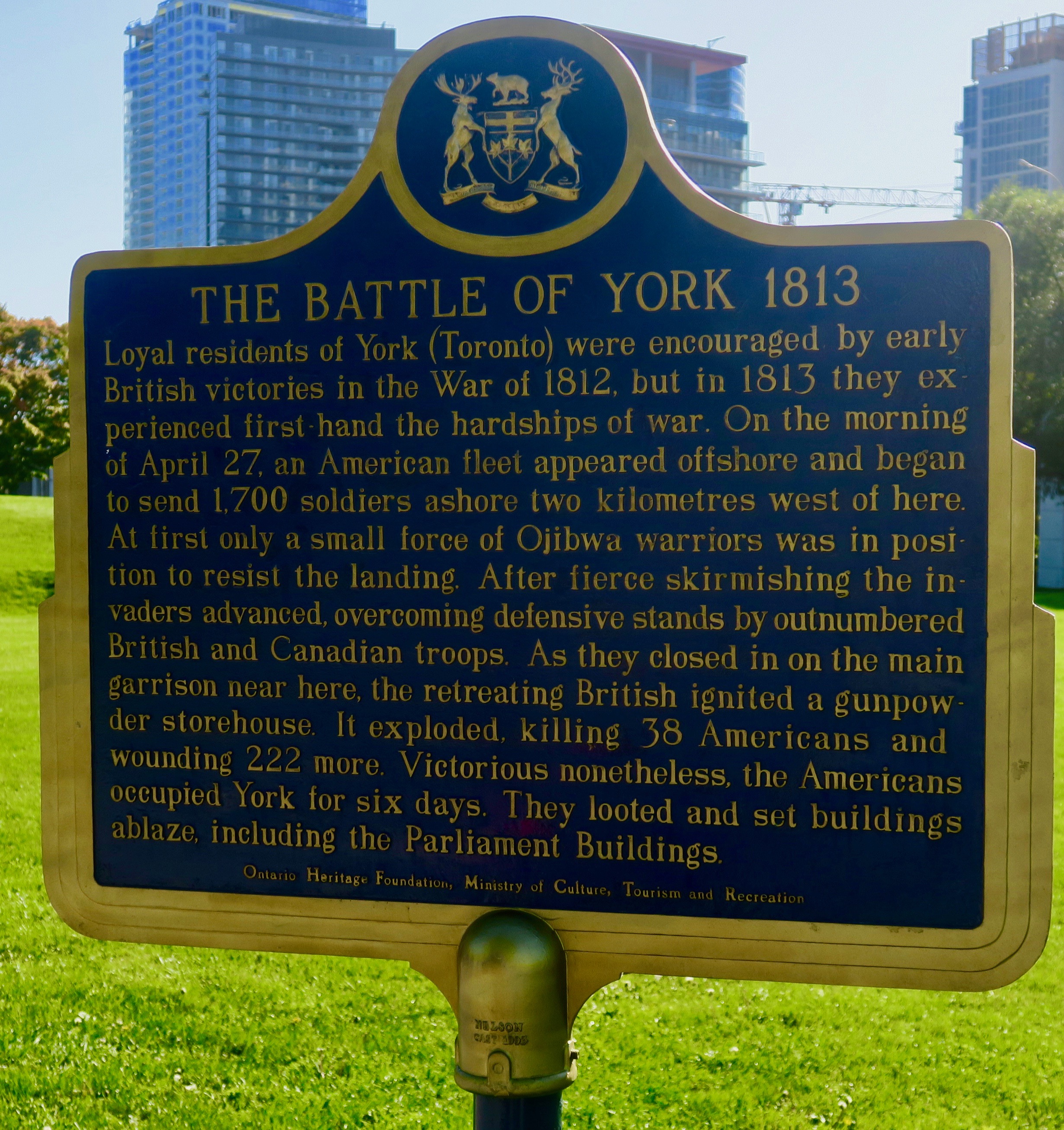

The Battle of York

The Americans and British did all they could to ensure that a war broke out between themselves in 1812, setting off one of the most stupid conflicts of all time in which no side emerged as a victor, no land changed hands and Isaac Brock got himself killed along with “Don’t give up the ship!” Captain James Lawrence who not only lost his life, but also his ship. There were literally dozens upon dozens of smaller skirmishes on land, sea and the Great Lakes, but few major battles. By my count the British won most of the land battles, but the Americans scored their single biggest victory right here at Fort York on April 27, 1813.

The establishment of Fort York was accompanied by the growth of the settlement of nearby York which had been named the new capitol of Upper Canada in preference to Kingston and Niagara. The seat of government was actually inside Fort York as it existed when the Americans attacked.

On April 26 a flotilla of fourteen American ships with between 1,500 and 1,800 soldiers aboard appeared seemingly out of nowhere just down the lake from Fort York. Landing on the 27th, they greatly outnumbered the defending forces that were composed primarily of British soldiers, a few Canadian militiamen and a number of Ojibway warriors. Under bombardment from the American ships and the ground assault the British commander, Major General Roger Sheaffe who also doubled as the Lieutenant Governor ordered a retreat, leaving Fort York to the Yanks. However, he did two things that greatly took the sting out of defeat and made this a mostly Pyrrhic victory for the United States. First he ordered the burning of the Isaac Brock which was under construction at Fort York and would have been the largest naval vessel on the Great Lakes. Capturing this ship was one of the motives behind the attack.

The second thing Sheaffe arranged was to blow up the fort’s powder magazine, but only after the Americans had invested the place. The American Commander Zebulon Pike a celebrated explorer (Pike’s Peak is named after him) and author, was killed along with 36 others while 222 were wounded. All told less than 130 people on both sides were killed in the Battle of York, something consistent with other battles of this war, which saw 15,000 Americans and 8,600 British and Canadians die. Compare that to Antietam some fifty years later where 23,000 were killed or wounded in one day during the Civil War.

After seizing the fort the Americans went on a looting rampage, burning the Legislative building and stealing the Parliamentary mace, which we only got back in 1934. It was this act that led the British to retaliate by burning the White House and Washington in 1814.

Having won the battle and burned the place down, the Americans found there wasn’t much reason to stick around and departed after a week of occupation. After that, the British and their allies returned and rebuilt Fort York. What you see today is this version that post dates the battle.

Visiting Fort York

Alison and I walked to Fort York from downtown which is about a one hour trek, but no doubt most people arrive by car. Even though it was a beautiful fall day there were only a couple of cars in the parking lot. The entrance fee is a bit steep at $14.00 – $10.00 for seniors, but we both agreed it was worth it. You start of in a modern building where there is a 15 minute video that definitely should be watched, a number of exhibits to be viewed and then you enter the actual Fort York grounds by going up an enclosed ramp where the battle is re-enacted. That’s the start of the ramp on the right.

Fort York proper consists of the largest collection of War of 1812 buildings extant anywhere most of which contain interesting exhibits within.

This is one of the few remnants of the fort that was attacked in 1813. It is the original west wall and dry moat with palisade stakes which obviously are not original.

Entering Fort York through the small west gate you then proceed through the gift shop and come out upon this scene that seems almost surreal. There’s the CN Tower and other modern buildings, dwarfing the buildings that, in effect, were their ancestors.

Once inside the fort you can tour the buildings and grounds in any order you wish. We decided to visit them clockwise starting with the South Barracks where I found a number of soldier’s uniforms hanging from wooden pegs.

There was nothing to say you couldn’t enlist, so I tried one on for size, adopting the haughty look British officers supposedly put on when there was any suggestion that colonials might make good soldiers.

These barracks once housed up to 100 men and were still in use right up until the 1930’s. As ordinary soldier’s barracks go these looked pretty comfortable. I’d sure as hell rather be here than in the trenches on the WWI battlefields.

However, the British military was nothing if not stratified by class differences.

This is the Officer’s Barracks.

How’s this for 19th century comfort?

The soldiers got pewter, the officers Spode china.

There are two original blockhouses which both date from the 1813 rebuilding of Fort York. Each contains a number of interesting exhibits.

This is apparently one of the rarest cannons in the world. It was cast in England during the Commonwealth period of rule under Oliver Cromwell between 1649 and 1660 so by the time Simcoe got his hands on it, it was already well over 150 years old.

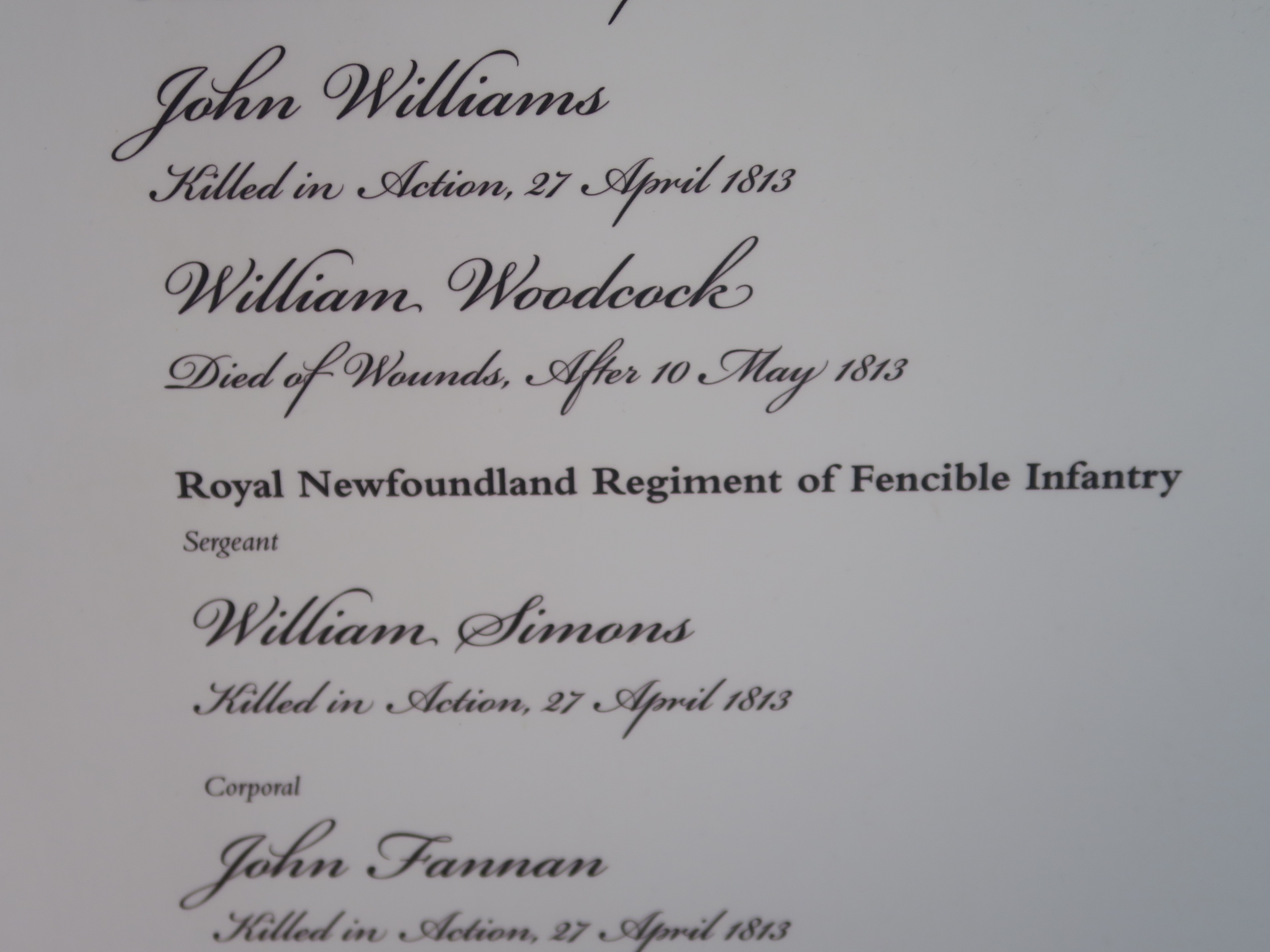

One of the exhibits gave a list of all the regiments that had troops at the Battle of York and I was taken by surprise to see mention of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment of Fencible Infantry which suffered a number of fatalities. Since Newfoundland did not join confederation until 1949, I did not know that they had been fighting and dying on Canadian soil for over 130 years before that time.

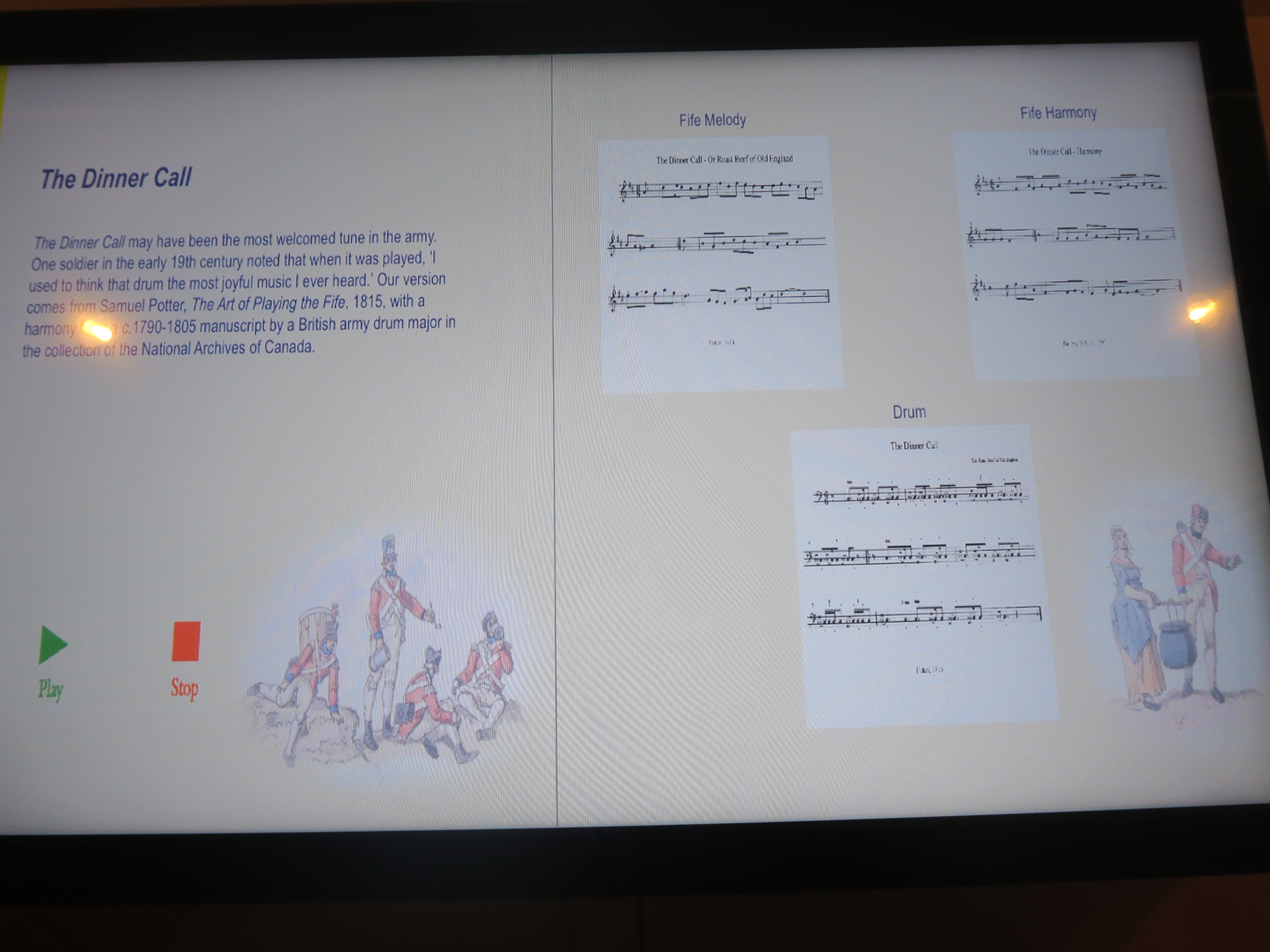

Perhaps the most interesting exhibit at Fort York is one that has to do with music.

Alongside an exhibit of martial musical instruments and uniforms there is this display that allows you to pick out and play a great variety of military calls. We all know about reveille and taps, but there are dozens more that every soldier would have recognized and that played a major role in military organization. One could easily spend a half hour or more just at this one spot listening to bugles, bagpipes, fifes, drums and other instruments.

Apparently the all time favourite for the soldier’s was the nightly call to dinner.

Another exhibit details the multiple travails that Fort York endured over the last hundred years to avoid simply being overrun by railway tracks, expressways and any number of projects that would have seen it either completely dismantled or moved. This is a view of the Gardiner Expressway from the original well that was dug in 1802. To me it illustrates perfectly the conundrum that pits the value of preserving one’s heritage against the demand of many, if not most, for modern convenience at any cost. I am truly appreciative that Torontonians seemed to have arrived at, if not perfect by any means, an acceptable compromise with respect to Fort York. If you live in Toronto you owe it to yourself and your kids to visit this place and recognize that the city actually has deeper roots than most would think.

If touring Fort York is a little tame for you how about a visit to the CN Tower for the Edgewalk? That’ll get your adrenalin flowing.