Minto Internment Camp Museum

Almost 99% of Canadian men and women who served either at home or abroad during WWII are now deceased. Memories of that worst of all worldwide conflagrations have faded and I am grateful for people like my friends at Liberation Tours for doing all they can to ensure that the sacrifices that were made for us and future generations are not forgotten. The reader will find many posts on this website from Liberation Tour sites in France, Belgium, Holland and Italy. While the primary focus for historians has always been on the war in Europe, Africa, the Far East and the Pacific, there is another aspect to the story and that is the effects of the war in Canada. Although not particularly controversial at the time, the war time internment of Canadian citizens has come to be a largely forgotten and, in retrospect, somewhat embarrassing part of our history. Many would just like to pretend it never happened, but it did and the Minto Internment Camp Museum in Minto, New Brunswick is where you can learn a lot more about this chapter of our history as I did on a recent visit.

History of the Internment Camp Program

If the reader has heard of the policy if internment of Canadian citizens during WWII, it is mostly likely in relation to the internment of over 90% of the Japanese/Canadian population. The War Measures Act was the legal pretence used to round up entire families, mostly in British Columbia and send the women and children to towns in the interior of B.C. while the men were sent to work camps. Many had their property confiscated as well. In 1988 the government publicly apologized and provided long overdue compensation. However, the reality was that the lives of most of the internees had been irrevocably shattered. The United States also interred over 120,000 Japanese Americans and if you want to get a better understanding of the consequences on an individual family I highly recommend reading Snow Falling on Cedars by David Guterson. It takes place on an island in Puget Sound, not unlike many of the islands on the Canadian side.

However, Japanese Canadians were not the only ones interned. German and Italian Canadians were also targeted, although to a much lesser extent. Others interned included Jewish refugees, Canadian fascists and even some Mennonites. Later, as the war progressed, German and Italian POWs, mostly merchant seaman, began to make up the bulk of the internees. All told there were 26 internment camps across the country with only in Atlantic Canada, that located in the small community of Ripples some 30 kms.(19 miles) east of Fredericton. However, its proximity to the town of Minto where most of the camp employees were from, led to its more common designation as the Minto Internment Camp and it is where you’ll find the museum that is preserving this important part of the area’s history.

The museum came about as the result of the efforts of one man, Minto teacher Ed Caissie who encouraged his students to build a model of the Minto Internment Camp, which they did and it is probably the most impressive item in the museum.

This photo shows only the core part of the camp which actually housed the internees. It was surrounded by five rows of barbed wire and has six machine gun towers. Outside of this compound there were many more administrative and residential buildings for the camp’s overseers. Officially known as Camp B/70 it covered 58 acres with 52 buildings in all. Before the war it had already been an unemployment relief station where men worked in the surrounding forests in exchange for meagre wages and room and board. The transition into the Minto Internment Camp occurred rapidly as many of the former forestry workers became soldiers and the camp took on the attributes of a prison.

After the model was completed, teacher Caissie, now joined by 60 students, began excavating the long abandoned site at Ripples and many of the artifacts they found eventually became the core of the museum’s collection. The museum is housed in the bottom floor of the Minto Municipal Building and there is no admission fee, although donations are more than welcome. It is not a large museum and it’s not going to overwhelm the visitor with jaw dropping dioramas or other such things. However, I will focus on a number of exhibits and a number of the people on both sides of the wire.

Let’s start with the people who actually ran the Minto Internment Camp.

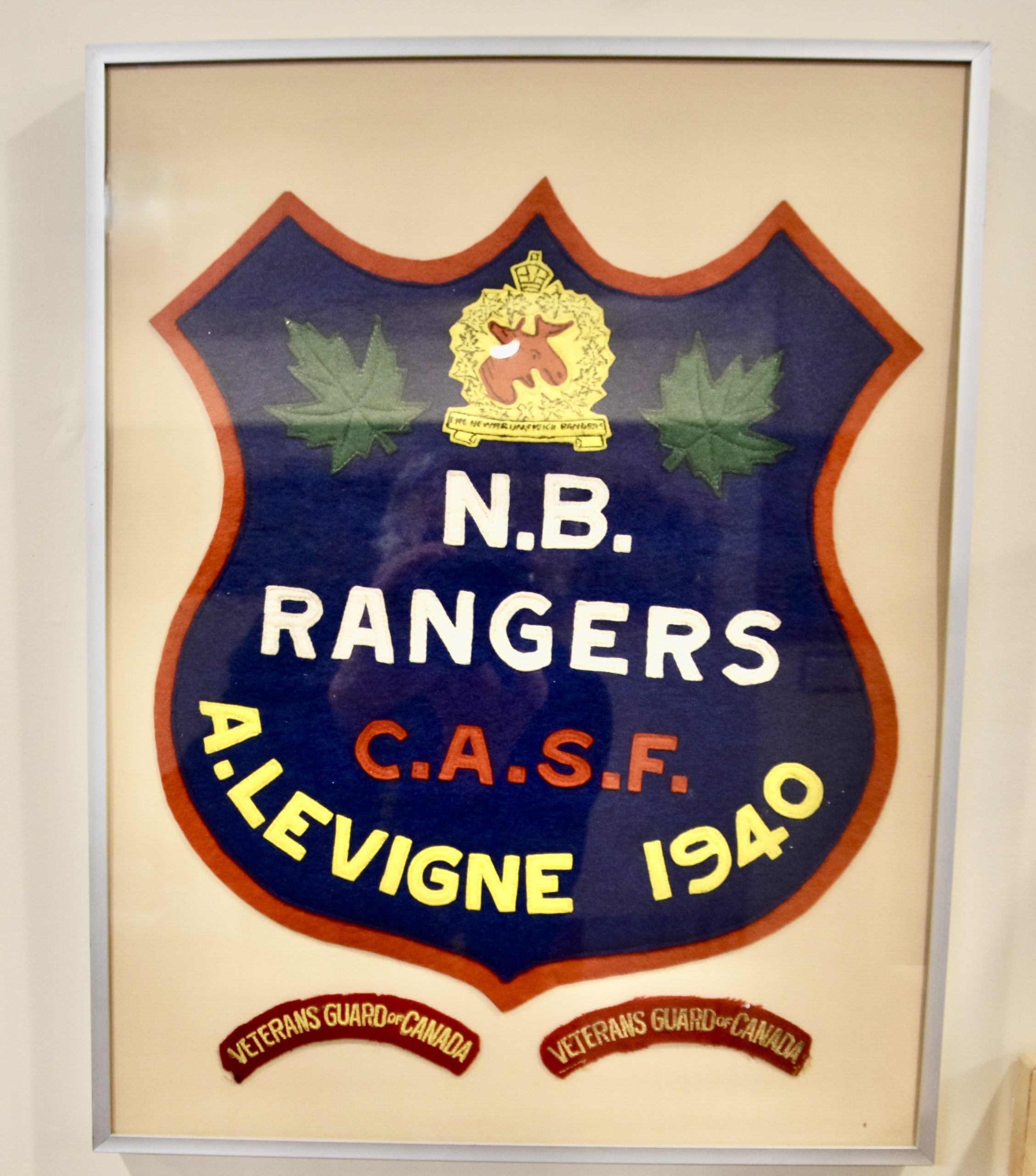

This is the New Brunswick Rangers patch of the Veterans Guard of Canada which was formed shortly after the outset of WWII. There were a lot of Canadian men, now in their forties and fifties, who had enlisted in WWI, but for one reason or another never made it overseas. They were eager to serve again, but were deemed to be too old for active service. Wisely, a term not often associated with military decisions, the government realized that these men had a lot to offer and using the British Home Guard as a model created first the Veteran’s Home Guard and then in 1940, renamed the Veterans Guard of Canada. At its peak in 1943, the unit had almost 10,000 members.

This is a photo of some of the men who served at the Minto Internment Camp taken from the museum’s website. You can see it in person along with dozens of other photos during your visit.

You can clearly see that these are older men, all serving their country as they were unable to do in WWI. However, according to the biographies of some of these men on the museum website, at least one, Albert Saunders, did serve overseas.

This is a cap and badges of the unit that is also on display.

While the story of the people who ran the Minto Internment Camp is indeed interesting, the story of some of the internees is even more so.

The camp went through a number of phases after its transition from an unemployment lumber camp to effectively a prison. Phase I held internees I had absolutely no idea about until I visited the museum – Jews who had fled Germany and Austria for Britain and were then shipped to Canada. Yes, we actually interned Jews during WWII. Why anyone who knew anything about what was going on in Nazi Germany during the late 1930’s could possibly think these refugees were Nazi sympathizers is beyond me. And yet, somebody in power apparently did. All told 711 Jewish men from age 16 to 60 were interned at the camp.

It took less than a year for ‘the authorities’ to realize that not only were these Jews not a threat, but could be a positive asset. One of the most notable example is the man on the right in this photograph, Fritz Bender.

Bender had a doctorate in chemical engineering with a specialty in polymers. He eventually was released in 1942 and went on to develop waterproof plywood which was used in the manufacture of the De Havilland Mosquito light bomber, a plane made almost entirely of wood.

Carl Amberg was only sixteen when he was arrested at Winchester school in England and shipped to the Minto Internment Camp. After his release in 1942 he went on to get a doctorate in chemistry from the University of Toronto and spent his career as an academic, eventually becoming Dean of Graduate Studies at Carleton University.

Helmet Blume was already a noted musician when he escaped Nazi Germany in 1940 only to be deemed an ‘enemy alien’ and shipped to Minto Internment Camp. After his release in 1942 he went on to a distinguished career with the CBC and became Dean of Music at McGill where there is a scholarship in his name.

Peter Oberlander was an Austrian Jew deported to Minto Interment Camp. After fleeing to London in 1938 with his family he apparently became an ‘enemy alien’ overnight once war was declared. After his release he became the first person in Canada to receive a doctorate in urban planning and went on to design Granville Island and the Toronto harbourfront.

Ernst Oppenheimer – yes we had our own Oppenheimer. He was a German Jew who first escaped to Italy and then to London and by now you know the story. All he did was get a doctorate from Harvard and create the German department at Carleton University.

John Newmark is the Anglicized version of Hans Neumark and the name he went by in Canada where he became a violinist of renown, known most famously for being the accompanist of Canada’s most famous opera singer, Maureen Forrester. He was inducted into the Order of Canada in 1973.

Max Stern was the son of a prominent Dusseldorf art dealer, had a doctorate in art history and inherited the gallery after his father’s death. In 1935 he received a letter revoking his gallery license so he relocated to London in 1936 and reopened it there. Almost incredibly four years later he was deemed an ‘enemy alien’ and off to the Minto Interment Camp it was. After his release he moved to Montreal, opened a gallery there and is credited with being the one who first promoted the works of Emily Carr, becoming her estate agent after her death.

You can find the details of these biographies and more on the Minto Interment Camp Museum website. What is clear is that Canada benefitted greatly from the incredible stupidity of the British government in sending these talented men overseas.

From what I can gather they were treated very well at the camp with the Quartermaster David Stark ensuring that they received Kosher food which he procured in Fredericton.

Phase II of the Minto Internment Camp began after all the Jewish men were released and POWs and others began arriving.

The Minto Internment Camp did have a few Canadians including Fritz Zeigler whose family had been Canadian citizens since 1913 where they were well know chocolatiers on the West Coast. This did not stop the authorities from sending him to Minto and then after his release keeping him under house arrest for the rest of the war.

Osveldo Giacomelli was one of the few Italian Canadians interned during WWII. He spent almost five years at the Minto Internment Camp and fought a long and ultimately unsuccessful campaign for compensation, dying before the courts could determine his claim.

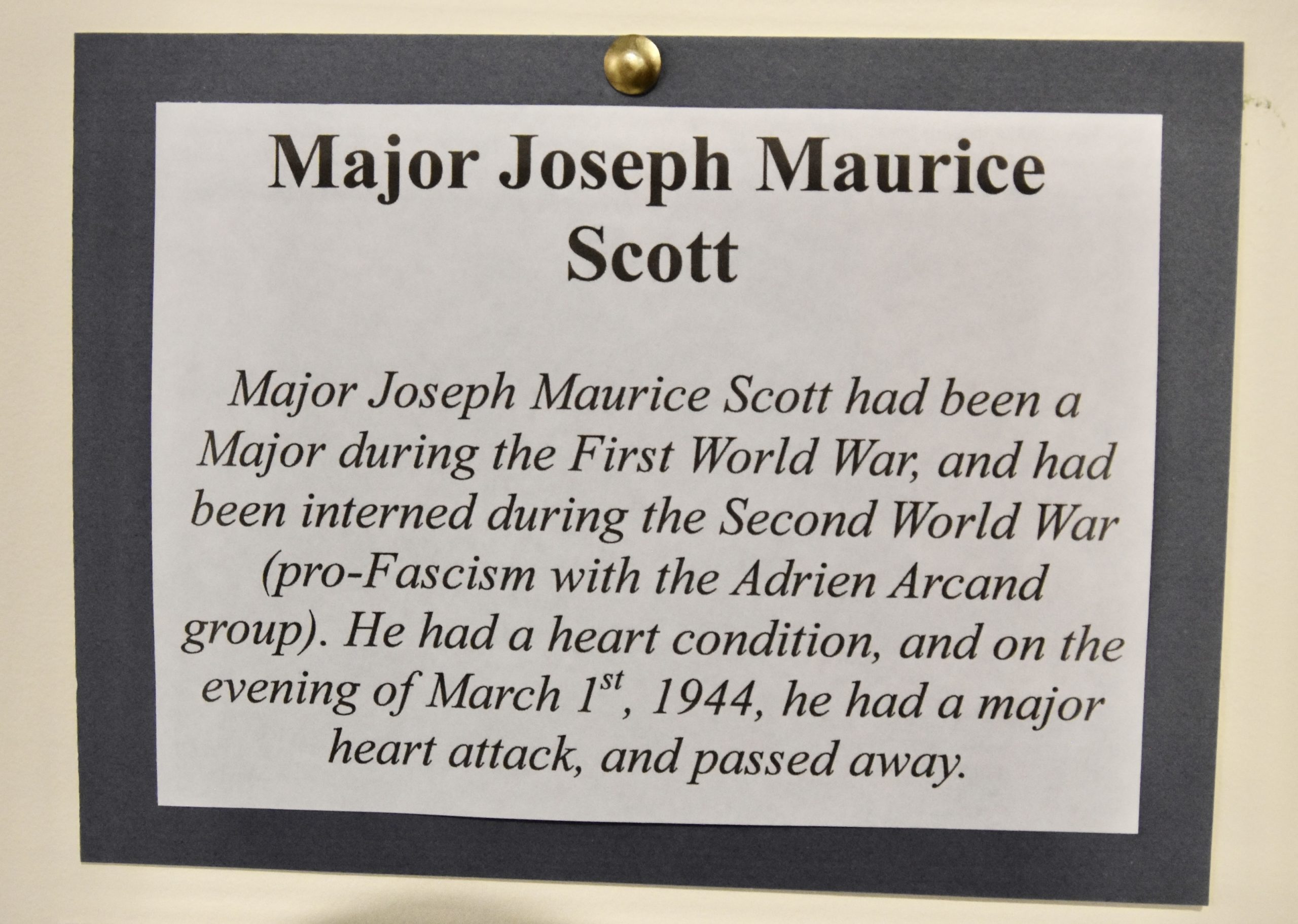

There might have been a few Canadians who did deserve to be interned and one of these was Major Joseph Scott. I can find nothing about him on the internet, but Adrien Arcand is described as ‘A fanatical and shrill-voiced follower of Adolf Hitler’ in the Canadian Encyclopedia.

The Artifacts

I can find very little about the German and Italian POWS who ushered in Phase II of the Minto Internment Camp as the Jews were finally being allowed to leave in 1941. This is a mock up of what one of the POWs cells would have looked. It’s not that different looking than the one’s in Hogan’s Heroes. In other words, pretty posh for a prison cell.

The one thing the prisoner’s did have was time on their hands and many of the most interesting artifacts are those created by these POWs.

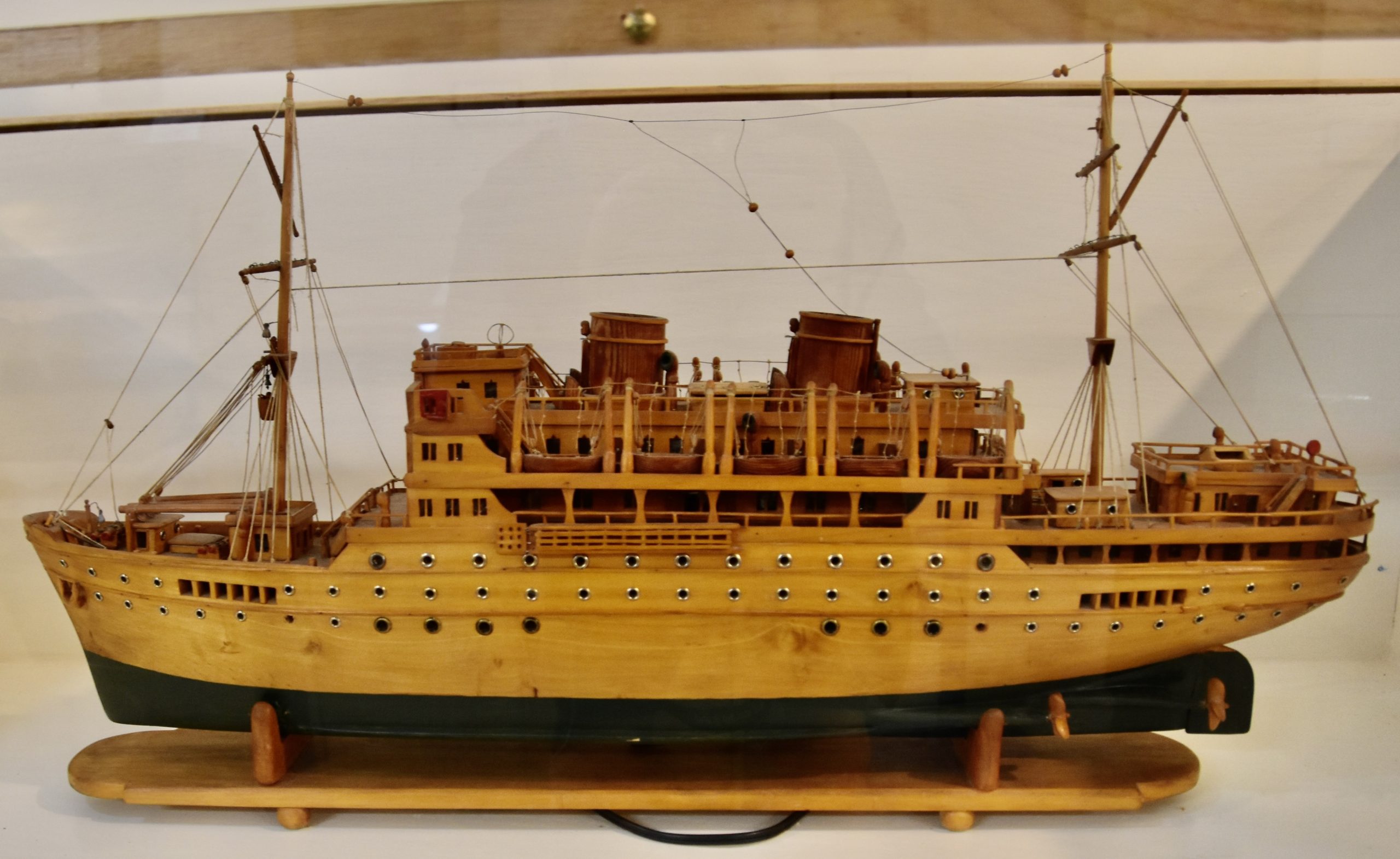

This is a model of the ship that brought one POW from Europe to Canada. It is one of many on display in the museum.

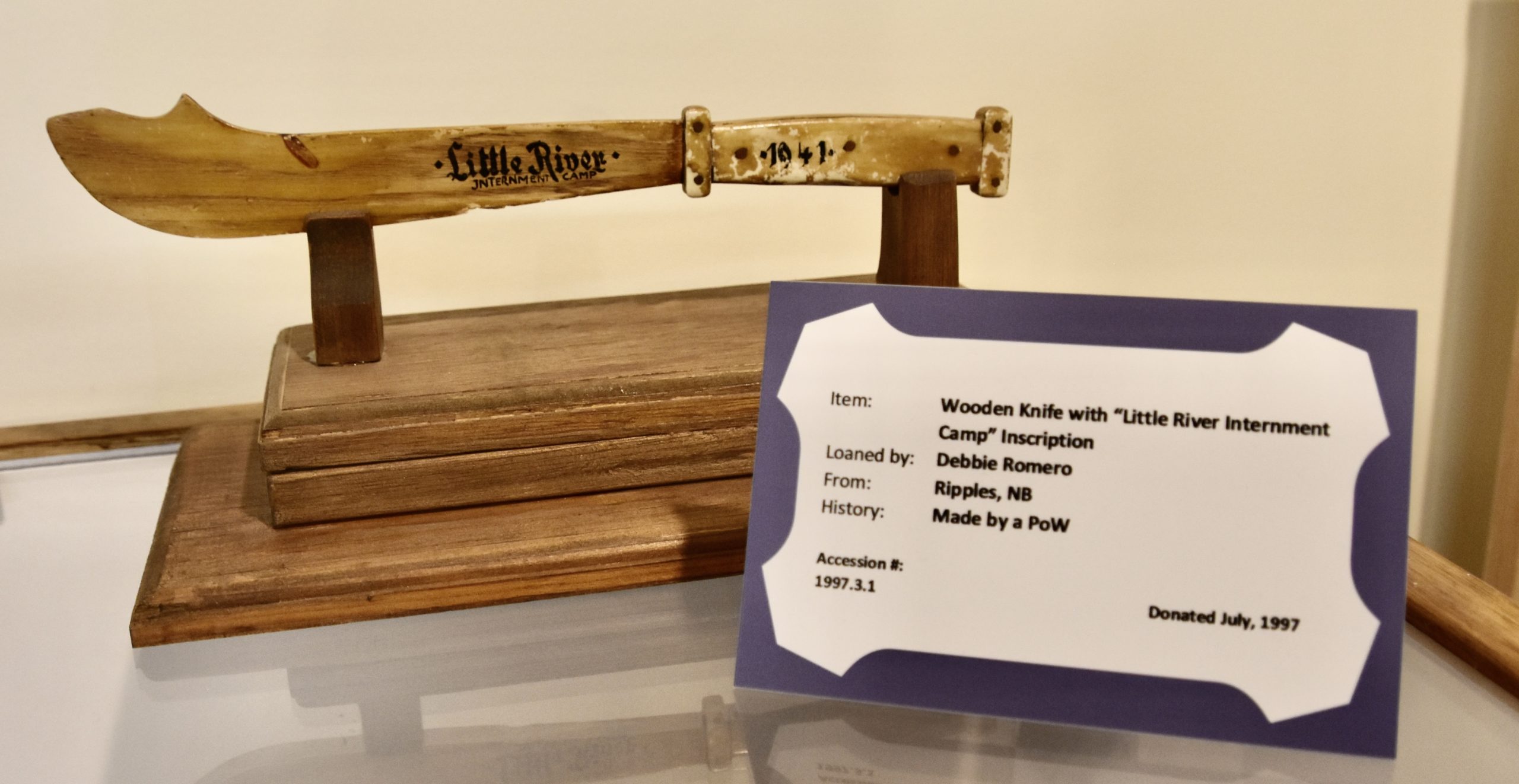

One of the things guards are always looking for in prisons are shanks or home made knives which are, for obvious reasons, prohibited. Yet at the Minto Internment Camp POWs were allowed to carve all manner of potential weapons which tells you a lot about the relaxed atmosphere of the place. I suspect the majority of the POWs were quite happy that the war was over for them and they would live to see the end of it. Who in their right mind would want to attempt to escape to get yourself back in peril?

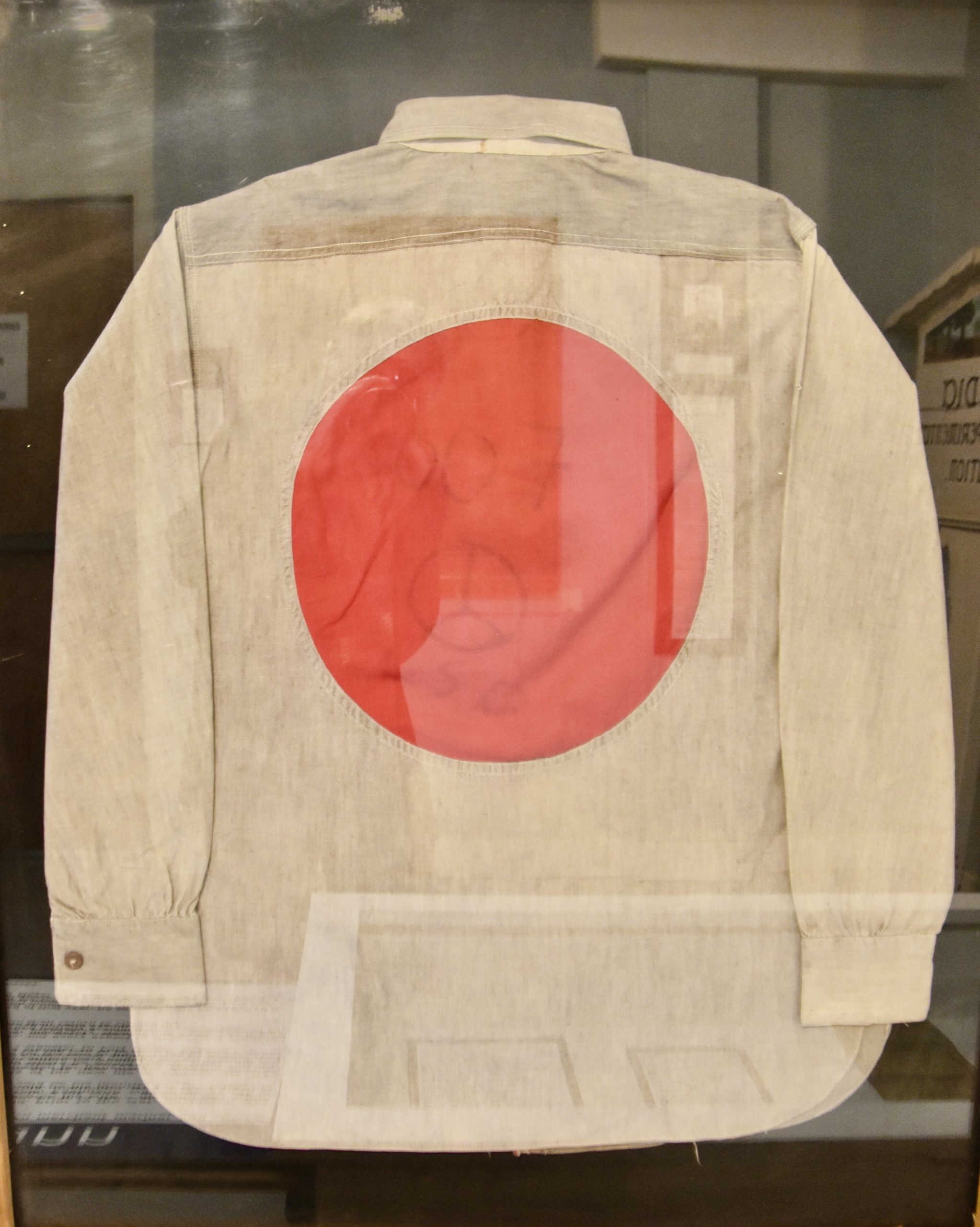

If they did try to escape they literally had a target on their backs as evidenced by this POW jacket on display.

My favourite artifact is this Hitler puppet which the museum is not sure was carved by a Jewish prisoner as a parody or a Nazi POW as an item of reverence. I suspect the former as I can’t imagine the guards condoning the carving of Hitler puppets by POWs.

While the great majority of the internees at the Minto Internment Camp made it out alive, not all did, Major Scott being one example. These are replicas of crosses that were carved here and erected in the Fredericton Rural Cemetery beside the Delta Hotel.

I can find no record that any internee was ever shot or otherwise done in by any of the Veteran Guards and you do not get the sense in visiting the Minto Internment Camp Museum that this place has a dark history, like the Death Railway Museum I visited in Thailand a few years ago..

Once the camp closed the buildings were sold off and there is very little to see at the actual site in Ripples. There is a trail through the now grown up woods with signs indicating where things used to be but that’s about it and the mosquitoes are pretty bad. To get the real story of the Minto Internment Camp you need to visit the museum.