The Dieppe Operation Part II – Visiting the Sites at Puys and Pourville

In the last post I described the planning and failure of the Dieppe Raid from the perspective of the assault on the beach that fronts the small city of Dieppe. If that were the only attack on Dieppe then it might fairly be called a raid, but in fact the there were attempted landings at five different sites, so for this post I am calling this Canadian disaster by its more correct designation, the Dieppe Operation.

Liberation Tour 2015 continued our visit to the important Dieppe Operation sites by climbing up the steep roads that lead out of Dieppe to the plateau above town and then descending once again toward the sea at the small village of Puy. In the previous post I described the reasoning behind the Dieppe Operation, why Canadians were the primary combatants and why it went so badly wrong. The events in that post were centred around the primary landing on the beach at the town of Dieppe. This post will describe events at Puys and Pourville as well as a visit to the Dieppe War Cemetery.

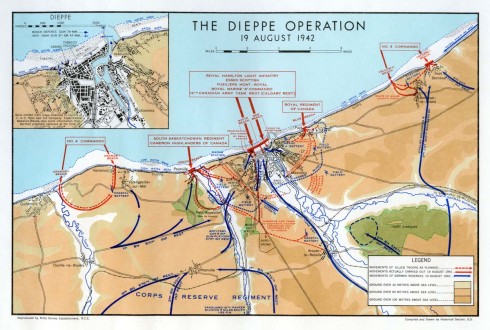

Here is a map of the landings at Dieppe on August 19, 1942. It will help illustrate the post.

The map indicates five distinct landing areas. The two outliers indicated by the red horseshoe shaped lines were the responsibility of British Commandos which had mixed results. The centre with the two strong red lines was the main attack described in the last post. Now we are headed to Puys which is just to the right of the main attack.

The Dieppe Operation- Puys

The road down into the village of Puys was so narrow that we had to leave the bus and continue on foot. As we neared the tiny beach I could see that there were cliffs on both sides – this was more the traditional idea of the Dieppe operation that I had in my mind based on stories in our grade school readers from grade five on.

As we neared the beach I saw this street sign.

And then we came to this memorial were tour historian Phil Craig explained the terrible fate that befell the Royal Regiment in the early morning of August19, 1942.

To put it simply, the Royals, mostly Toronto boys, never had a chance. The Germans had been alerted and were waiting with machine guns placed strategically to cover the entire landing area. Of 556 men in the regiment that day over 200 were killed outright and all the rest who got ashore save one man, Cpl. Les Ellis were captured. This was the highest casualty rate suffered by any Canadian regiment in WWII and it’s hard to conceive of how it could have been worse. Above is a horrible picture taken by the Germans of the Canadian dead at the base of the seawall at Puys. I honestly don’t think we could get any soldiers today to do what the Canadians attempted at Dieppe and that’s probably a good thing, but let’s never forget that they tried.

Today Puys has returned to its long tradition as a summer resort for people wanting to avoid the limelight. This mosaic near the beach commemorates visits by authors Georges Sand, Marcel Proust and Alexandre Dumas. Earlier visitors include Joan of Arc and Julius Caesar.

Today the sea is calm and these two fishermen are the only ones on the beach. I wished them good luck as we headed back up the hill to the bus in an understandably sombre mood.

The Dieppe Operation – Pourville-sur-Mer

Pieter, our very competent bus driver, negotiated the way back down to the Dieppe plain, through its back streets and back up once again to the small village of Pourville-sur-Mer for our third Dieppe Operation landing site of the day. It was here that the South Saskatchewan Regiment and the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders came ashore and achieved considerable success in penetrating towards their inland objectives, but with the total failure of the main landing and that at Puys, they were soon forced to retreat. The second VC of the day was won at the Pourville Bridge over the River Scie.

Phil related in stirring terms the story of Lt.-Col. Charles Cecil Ingersoll Merritt.

Lt. Col. Merritt was a professional soldier and he looks every inch a man the Germans would regret confronting.

Here is what he did to earn the VC as part of the Dieppe Operation.

From the point of landing, his unit’s advance had to be made across a bridge in Pourville which was swept by very heavy machine-gun, mortar and artillery fire: the first parties were mostly destroyed and the bridge thickly covered by their bodies. A daring lead was required; waving his helmet, Lieutenant-Colonel Merritt rushed forward shouting ‘Come on over! There’s nothing to worry about here.’

He thus personally led the survivors of at least four parties in turn across the bridge. Quickly organising these, he led them forward and when held by enemy pill-boxes he again headed rushes which succeeded in clearing them. In one case he himself destroyed the occupants of the post by throwing grenades into it. After several of his runners became casualties, he himself kept contact with his different positions.

Although twice wounded Lieutenant-Colonel Merritt continued to direct the unit’s operations with great vigour and determination and while organising the withdrawal he stalked a sniper with a Bren gun and silenced him. He then coolly gave orders for the departure and announced his intention to hold off and ‘get even with’ the enemy. When last seen he was collecting Bren and Tommy guns and preparing a defensive position which successfully covered the withdrawal from the beach.

Lt. Col. Merritt was captured and spent the rest of the war as a POW. He died in Vancouver in 2000. I wonder how many people who knew him after the war had any idea of the feats of courage he was capable of under conditions we can only imagine in our worst nightmares.

When we visited the D-Day beaches I couldn’t help but think that the combination of blue skies, beaches and the multiple hues of the ocean would have attracted the Impressionists and today I’m glad to be proved right. Claude Monet, the most prolific and probably most popular of the Impressionists did paint at Pourville. Here is my photograph of beautiful Pourville Beach.

And here’s how Monet portrayed it

Once again we made our way back up to the top of the cliffs and headed for the look off just beside the castle for one final view of Dieppe. From here you can see just how exposed the Canadians were to fire from this position.

The Dieppe Canadian War Cemetery

Our last stop before heading east to the WWI sites was at Dieppe Canadian War Cemetery in Hautot-sur-Mer, just outside of Dieppe proper, tucked away down a narrow lane in a bucolic countryside that is the antithesis of anger, war and hate.

As we got out of the bus I noticed this van with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission symbol on it.

Phil and John had told us that they understood restoration work was going on at the Dieppe cemetery and so it was. Rather than detract from the experience it in fact enhanced it, as it was uplifting to see the respect with which these graves were being afforded as they were reinserted into place.

Despite a substantial part of the cemetery being roped off for restoration work, I was still able to get a view of the symmetry of these places that has really grabbed me. There is just something about the endless rows that, while not diminishing the importance of each individual grave, magnifies the effect of the entire insanity of war.

As per usual I took a few photographs of graves of soldiers just to see what I could find out about them other than what was on the headstone. Here is Sgt. Lewis Robley Graham of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, son of Gordon McGregor Graham and Florence Ryder Graham. Despite being 35 years of age he was unmarried. He would have been one of those who died at Pourville. Note that he is listed as being “Buried Elsewhere in This Cemetery” which means they know his body is here, but not where.

Here is Flying Officer Leslie George Stamp who was a wireless operator/air gunner who died on August 5th, 1944. That is the same position my father held in the RCAF in WWII. Although this is an RAF grave, the records indicate F/O Stamp was with an RCAF squadron. It could just as easily been Mr. Stamp’s relatives looking at my father’s grave if things had gone differently.

Next is D. Jones who for some reason does not appear in the on line list of those buried at Dieppe, but I can attest that he is there. A couple of things about this grave struck me; first he was in the Merchant Navy and second he is listed as a Donkeyman. A little research indicates that this was someone who worked on the smaller or donkey engines inside a merchant ship. It would have been hot and dirty work. I can’t find any about the ship SS Benjamin Sherburn on which he served. Most strikingly, he was 52 years of age.

There are 187 graves in this cemetery with the caption ” A Soldier of the Second World War”. It seems incredible to me that with modern DNA testing that more could not be done to identify the remains of at least some of these 187. We surely know the names of those Canadians who were never identified after the Dieppe Operation and how hard would it be to get DNA samples from living relatives and test each of the unknown remains against the database from the DNA samples. After all, if they could positively identify Richard III by way of DNA testing on modern day relatives, how hard could it be for the poor unknown souls buried here?

On that note we leave Dieppe and head for the great slaughterhouse of the Western Front in WWI. Was the Dieppe Operation just as futile as those massed infantry attacks in WWI? Did these Canadians die in vain? After being here I find that hard to accept. Maybe there is such a thing as a mitigated disaster. Learning how not to do things can be instructive and I want to think that the consequences of the Dieppe Operation led to a realization that any future landings had to take place on shallow beaches away from fortified port positions, which is exactly what happened almost two years later in Normandy.

RIP Dieppe vets, your sacrifices will never be forgotten.

Tomorrow we switch focus as we begin our tour of WWI sites, but not before taking time off to visit amazing Amiens Cathedral. Please join us.