Beaumont Hamel – Newfoundland’s Darkest Hour Must Not be Forgotten

Liberation Tour 2015 continues its tour of Canadian WWI sites at a place that is both deeply important to all Canadians and at the same time a memorial to those who died fighting, not for Canada, but for Britain. In 1916 Newfoundland was still a British colony with no political affiliation with Canada and the events on one July morning at Beaumont Hamel forever transformed the future of that rugged island and its rugged people. In my previous post I wrote about the absolute insanity that was WWI and the unprecedented casualties suffered on the Western Front. In this post I want to concentrate on the consequences to one regiment on one morning on one day in July, 1916.

Royal Newfoundland Regiment

At the outbreak of WWI Newfoundland had just under 250,000 residents and no standing army. Like the other Dominions, volunteers for military service rushed to enlist and before long the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, which had ties going as far back as 1795, was at full strength and attached to the 29th Division of the British Army. The 29th was an amalgamation of Irish, English, Scots, Welsh, Guernseymen and the Newfoundlanders that fought first at Gallipoli and then at every major Western Front battle from the Somme onward.

The men who were about to fight at Beaumont Hamel had already seen action at the disastrous Gallipoli campaign in Turkey, in particular at Suvla Bay where they lost forty of their number. When the decision was made to withdraw from Gallipoli, the Newfoundlanders, based on their singular performance at Suvla Bay, were chosen for the rearguard and were among the last to leave Turkish soil. Little did they know they were leaving one hellish place for a worse one.

Battle of the Somme

The Newfoundlander’s role at Beaumont Hamel can only be understood by looking at the much bigger picture of the Battle of the Somme that began on July 1, 2016 and was supposed to be the ‘big push’ that would break the stalemate and end the war. Plans had been underway for an attack that would consist primarily of French forces supported by the British and colonials. However, the Germans struck first by attacking the strength of the French at Verdun, essentially tying up most of those forces and leaving the Somme to the Brits. Here is a map of the grand plan as drawn up by the ‘geniuses’ at Allied headquarters. You can see the 29th to the right of Beaumont Hamel. The red line represents the Allied trenches, the solid blue line the German front lines and the two dotted blue lines the second and third German lines.

You can also see the straight red arrow indicating that all the 29th had to do was storm through the German front line and then make their way to the German second line and take that – piece of cake, right? It probably did appear that simple to that greatest of British military idiots, General Douglas Haig, the man who designed the Somme offensive along the same lines as numerous previously failed attempts to attack entrenched positions using infantry after an artillery bombardment. What should have been learned from these disasters was this.

1. Artillery bombardments are not very effective against an enemy who is dug in. Do not expect to find the enemy lines decimated by your great gunnery. Expect to find the enemy mostly intact, if somewhat deaf.

2. Artillery does little or nothing to disrupt barbed wire and other man traps set in No Man’s Land. Expect your infantry to encounter almost impenetrable conditions once they leave the trenches.

3. Barbed wire offers little protection from machine gun bullets. So while your men are clipping their way through the wire, expect most of them to be killed or wounded.

4. Don’t set unrealistic goals for your men such as traveling hundreds of yards through No Man’s Land in a matter of minutes.

5. When your first attacks are decimated don’t compound your errors by sending a second and a third attack to suffer the same fate.

The well known definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again while expecting a different result. Considering that Haig learned nothing from his previous campaigns, it is quite arguable that he was insane.

OK, so that’s the background to Beaumont Hamel. I guess I’ve tipped my hand on how it’s going to turn out for the Newfoundlanders. Let’s see what it’s like today.

Visiting Beaumont Hamel

As the bus makes its way from the lovely cathedral city of Amiens through the verdant spring countryside of the Pas-de-Calais I cannot help but notice that where other landscapes feature fields, wooded copses and ancient farms, this one has something else. There are literally cemeteries everywhere. The Somme is a place that grows graves.

Beaumont Hamel is one of two WWI sites that is actively managed by Veteran’s Affairs, the other being Vimy Ridge. We spend about fifteen minutes in the visitor centre which has this extraordinary map of Newfoundland which, upon closer inspection, is actually a collage of faces.

In 1914 Newfoundland was still an almost totally rural island with hundreds and hundreds of tiny fishing outports that are mostly long gone today. Inside the visitor centre there is a list of these places which Newfoundlanders who served in the war, called home. I specifically look up Tilt Cove, which was a mining community that had almost 1,400 residents in 1900. My great grandfather was a doctor there and it was the birthplace of my grandmother. Today it has five residents.

Student volunteers lucky enough to be chosen from among the hundreds who apply, give 50 minute guided tours of the battlefield after which visitors are free to wander the park on their own. Here we are setting out with our guide and tour leader John Cannon.

The first thing of importance we come across is this communication trench which connected the secondary line to the front trenches. After almost 100 years it is clearly visible.

The reason I say it is important is because it was through here that the Newfoundlanders made their way to front lines from where they would be the third wave of attackers. This dispels a persistent myth that Newfoundlanders were essentially used as cannon fodder while British troops were spared. While they certainly were used as machine gun fodder, so were the other regiments who preceded them that day. Everybody got an equal chance to die.

If there is one nice thing about visiting Beaumont Hamel is it the iconic caribou statue that sits high atop a ridge overlooking the battlefield.

From the vantage point of the caribou you can what a hopeless situation the Newfoundlanders and others were put in that day. Here is the view over the battlefield to the German trenches a good 300-500 yards away. To expect men to cross that open field, covered in barbed wire, completely exposed to German machine gun fire and in the case of the Newfoundlanders, already littered with the dead and dying from the first two assaults, is unimaginable to me. You would have to know that you were almost certainly giving up your life in the next few minutes.

Here is the front line trenches from which the Newfoundlanders somehow found the courage to propel themselves into their own Armageddon.

Very few of them made it as far as what was known as the Danger Tree, a single blasted tree which provided no real protection from enemy fire. Here is what it looks like today, although I’m sure it’s a different tree. Note the small crosses placed underneath.

From the Danger Tree the few Newfoundlanders who made it here, had this view of what was left to cover. The German trenches are over by the tree line.

Believe or not a few men did make it to the German trenches where most were killed, falling in the barbed wire that surrounded the German line. Of the almost 800 Newfoundlanders who went over the trenches that morning only 68 survived unscathed, 324 were killed outright and 386 wounded, many dying later. It was the single worst day in Newfoundland history.

Thanks to Haig’s refusal to learn 20,000 men were killed in the Somme on the morning of July 1, 1916.

Our guided tour ends at the Danger Tree and we wander on, in kind of a daze, towards the cemeteries in the distance. No Man’s Land has long surrendered to sheep fields and while we are not permitted to cross the fence because of the danger of unexploded ordnance, the sheep, unable to read, are quite happy with their lunch of grass and shrapnel.

Beaumont Hamel Cemeteries

This is Y Ravine Cemetery, so named because of the Y shaped ravine which the Germans used as a natural defence at Beaumont Hamel. While there are over 400 soldiers interred here, only 275 are identified. This will become a disturbing feature of WWI cemeteries.

Here are the graves of Richard Joseph Maddigan, aged 19, son of Richard and Ellen Maddigan of 259 Water Street, St. John’s and Isaac Moss, also 19, son of James Moss of Tunstall, Stoke-on-Trent, England. I can only presume that their remains were so intertwined that they were buried together; two teenagers who died uselessly for King and country on July 1, 1916.

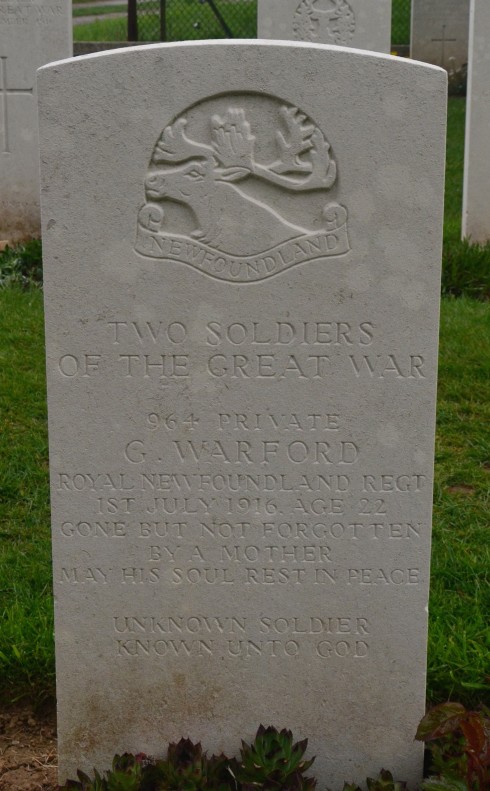

Here is Garland Warford, 22, son of William and Susannah Warford of Upper Gullies,NL buried with an unknown soldier.

We move on to Hawthorne Ridge Cemetery # 2 where another 200 are interred of which one quarter are unidentified. Notice how for some reason most are buried with no space between the graves.

This is Sgt. Charles Reid, 30, son of George and Jessie Reid of St. John’s. He could very well be a relative of mine as my Newfoundland grandmother had Reid relations. He too has an unknown resting mate. Even though they are not, the flowers at the base of the grave remind me of the pitcher plant that is a symbol of Newfoundland.

Lastly we trudge by Hunter’s Cemetery which is actually a giant shell hole where 41 soldiers, mostly highlanders, were buried after being killed at Beaumont Hamel.

This is the monument to the fallen highlanders that is at the far end of the battlefield from the Caribou monument.

We make our way back to the visitor centre and pass by the Caribou monument one last time. Our guide had explained that it is but one of five similar monuments in France and Belgium. On a future trip I hope to seek out the other four.

The last memory I take away from Beaumont Hamel is this plaque. It has over 800 Newfoundland names on it. At first I stupidly think it is a list of all those Newfoundlanders who died during WWI and then I look closer. It is the names of those men who simply disappeared. The ones that lie buried unnamed beside Sgt. Reid and Garland Warford and hundreds of others. Ones buried under tons of earth whose bodies were never found. Ones blown so badly apart as not to be recognizable as a human remain.

Today we, quite rightly, get very concerned when persons simply go missing. Can you imagine what would happen today if 800 young men from a province as small as Newfoundland simply disappeared?

That’s all I can write about Beaumont Hamel. I need to get back on the bus and try to think rational thoughts about this most irrational of wars.

RIP Newfoundlanders, we will never forget.

Next we continue our tour of the Battle of the Somme by focusing on two personal stories out of the million who died.