Batoche – The Last Major Battle on Canadian Soil

I have to confess that for many years, my feelings about Louis Riel and the outcome of the two Métis rebellions he led, were quite mixed. Over the years my views on him have evolved from – 1. treasonous rebel who deserved to be hanged to 2. misunderstood madman who probably shouldn’t have been hanged to 3. a leader fighting for a genuine cause who definitely should not have been hanged. Something tells me that this is an evolutionary path that most Canadians, particularly anglos, have followed over the past fifty years. Alison and I travelled to Batoche National Historic Site not only to see the scene of the last major battle on Canadian soil, but also to learn more about the Métis people and why they twice unsuccessfully clashed with the Canadian government during its infancy. Won’t you join us on this quest?

Who Were the Métis People?

I am using the past tense in reference to the Métis people not because I don’t know that they continue to exist today, but rather to examine a way of life that has disappeared. In the landmark decision of R. v. Powley, the Supreme Court of Canada recognized Métis rights and linked them to the ability to prove that one had ties to an historic Métis community. Métis community was in turn was defined as one made up of individuals of mixed European-Aboriginal ancestry, with a distinctive social identity, in a distinct geographic area and sharing a common way of life. Many people mistakenly believe that a Métis is someone who is half French and half aboriginal. While most Métis probably fall into that category, many have no or very little French blood. My first wife was a Métis with both of her parents having both European and aboriginal forebears. Her mother was an Azure, which is a French name, but her father traced his European ancestry through a Welshman by the name of Lundie. By blood, my son and grandsons could also be considered Métis, but they would fail the test because they’ve never lived in a Métis community or pursued a Métis way of life.

Obviously because by definition a Métis must have some European DNA, their culture can date only from first contact between Europeans and Indigenous peoples. However, there is a great debate today between historians, anthropologists and Indigenous organizations as to whether or not communities east of the prairies can be considered to be genuine Métis. I’m not going to wade into that argument, but will stick with the communities that started around the Red River in Manitoba and spread west from there. By the late 1700’s the prairie resources were being exploited by both the London based Hudson’s Bay Company and the Montreal based North West Company. The trade was primarily in furs and the Métis played a substantial role by provisioning the North West Company employees with buffalo meat or the pemmican made from the meat. The Métis roamed the entire Canadian west, but were, at that time, based out of the nascent Red River settlement around present day Winnipeg.

It was the arrival of a group of dispossessed Europeans in 1812 that really started the friction between the Métis and what I’ll call ‘The Authorities’. Lord Selkirk’s settlers were Scottish highlanders and some Irishmen who had been removed from their traditional lands as a result of the infamous Highland Clearances. Selkirk was trying to do the right thing by them and obtained a grant from the Hudson’s Bay Company of what became the Red River Colony. Unfortunately, this was the same land that was to a large extent already occupied by the Métis and their aboriginal allies. Two people cannot occupy the same land and in 1815 a Métis party led by Cuthbert Grant killed the colony’s governor and twenty other men at what is now euphemistically called the Battle of Seven Oaks. When I was growing up this was called the Massacre of Seven Oaks as that was really what it was, the Métis having surrounded the settlers and cutting them down with only one casualty.

This is a classic case of turning the old adage, “History is written by the winners”, on its head. In the first version, written from the settlers point of view it was a massacre. In the revisionist version, written from the other perspective, it was a battle and a victory. It illustrates very well that history is a fluid discipline and that while actual facts cannot be changed, how those facts are interpreted can. By now you are probably wondering when I’m ever going to get to Batoche, which is hundreds of miles and sixty years away. To me, you cannot understand the consequences of any historical event, especially a major clash between two very different cultures, without understanding what preceded it. And sometimes that can literally be a build up of hundreds of years. It’s also important because that clash of cultures is still going on today, albeit with lawyers and judges as the major combatants.

In 1821 the North West Company and Hudson’s Bay Company merged and tensions in the Red River Colony subsided. Both the Métis and an increasing number of European colonists engaged in agriculture along the Red and Assiniboine River as well continuing to trade in furs. There were tensions for sure, whether between pure blooded Europeans and the Métis and Indigenous peoples or between Catholics and Protestants, but overall life went on without further bloodshed. That all changed in 1869.

Louis Riel and the Red River Rebellion

Although the Hudson’s Bay Company had technically governed the vast area that now comprises the three prairie provinces and much of the Northwest Territory, it really had no true governance presence in any but a few places like the Red River area. By 1869 the company’s long run as a major player in North American affairs ended when it sold it’s remaining lands to the new Dominion of Canada. Not surprisingly the ‘sale’ upset both the Métis and the Indigenous peoples who thought that the land belonged to them. At the very least, they thought they should have had a say in the process and it’s pretty hard to argue with that.

Louis Riel emerged as a leader and representative not only of the Métis people of the colony, but also the original European settlers and others who would be adversely affected by the transfer of their lands to a new country. To make a long story short, Riel’s attempts to block Canada from taking control of the territory failed and morphed into a negotiation which eventually lead to the creation of the province of Manitoba. So in one sense, Riel was really a father of confederation. Part of the deal included recognition of Métis rights, which were promptly ignored.

While Riel was the head of semi-legitimate provisional government in that it represented the interests of the majority of the area’s inhabitants, to ‘The Authorities’, he was a rebel. Riel stupidly confirmed them in this opinion by executing one Thomas Scott, a recent arrival from Ontario. While Scott was a loud mouthed Orangeman with vitriolic anti-Catholic views, Riel had no authority to be his judge, jury and executioner. The execution inflamed Protestant Ontario and Riel ended up having to flee to the U.S. as a wanted criminal.

The Settlement of Batoche

After Manitoba became a province, hundreds of new agrarian settlers moved in and most of the Métis gradually moved further west, including to the community of Batoche in central Saskatchewan, which was established by one Xavier Letendre in 1872. By 1885 there were 500 people in the community. Reliance on the buffalo herds was no longer feasible, so the Métis adapted to farming, using the system of land ownership started in Quebec whereby every land owner got a piece of land on the river. Batoche in 1885 would not have looked much different than hundreds of small towns in Quebec along the St. Lawrence River. The dominant structures were the church and the rectory, with most of the population living in very simple wood cabins.

Batoche has a beautiful location high on the banks of the South Saskatchewan River midway between present day Saskatoon and Prince Albert. It’s quite off the beaten path and there is almost no trace of what was once a thriving community. It is a fallish day late in August as Alison and I drive into the almost deserted parking lot at Batoche National Historic Site. Entry is through a fairly new interpretive centre which also houses a small restaurant where you can sample bannock, a staple of Métis cooking. There are a number of dioramas and other displays that explain Métis life both before and at Batoche. This very life- like representation of the aftermath of a bison hunt depicts life before the necessity of turning to agriculture.

One cannot forget the fact that the Métis, although initially following a lifestyle that was closer to aboriginal than European, nevertheless still held many European values. Almost every picture you see of Louis Riel and his comrades shows them in a suit and tie. This display of artifacts from the time that Batoche was settled shows just how important Old World goods were to the average Métis family by 1880.

However, when they were pursuing game or generally working outside this is how a typical Métis might have dressed. Note the Christian symbols on the leather trousers.

The Catholic Church played and still continues to play, a major role in Métis life. The only two original buildings surviving in Batoche are the church and rectory and we are off to visit them next.

The church, properly called Saint-Antoine de Padoue, was built from 1883-85. By coincidence Alison and I will be visiting Padua in just over a month’s time and will see the original church dedicated to this Portuguese saint.

There is a costumed guide at the entrance and we are given our own private tour. Other than the large stove pipe, this could be the interior of any small rural Catholic church almost anywhere in the world.

More interesting is the Rectory building next store, which also doubled as the Batoche post office.

Every Catholic church had a rectory which served as the living quarters not only for the parish priest, but any others required to maintain the church’s presence in the area. In the case of Batoche, this included a housekeeper/cook, a brother (not a priest, but one committed to a life of piety and chastity) and a choir boy. A room by room tour of the rectory reveals a very comfortable place to live, study and work. This is the post office.

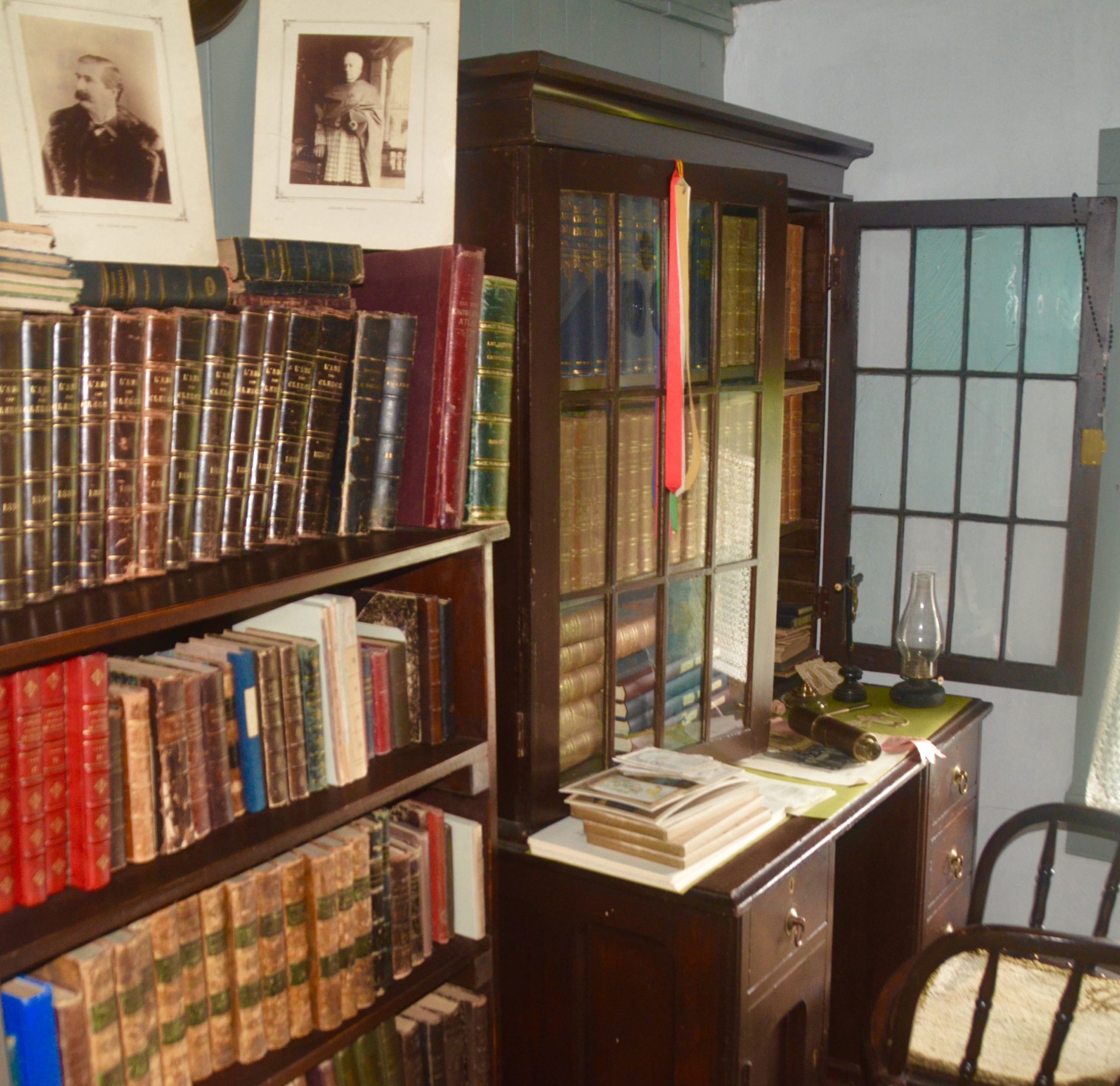

The priest had his own library, which by the standards of the day, seems pretty well stocked.

As well as his own private devotional space.

This is the room where the brother and the choir boy slept, with their vestments hanging neatly on the wall.

Downstairs in the dining room I couldn’t help but notice this Nova Scotia glass compote in the Diamond Ray pattern. This pressed glass was produced from just after confederation until WWI at several factories in Pictou County, Nova Scotia. The Catholic church was one of the best customers, buying huge quantities for the many seminaries in Quebec and elsewhere. It was very interesting that this piece had made it all the way to Batoche and was in pristine condition.

Just visiting Batoche, without regard to the events that happened here in 1885, you’d have to conclude that it was a pretty comfortable and ‘civilized’ place. With the demise of the bison herds, the Métis lifestyle had changed dramatically, but they seemed to have adapted quite well to becoming farmers and merchants. So what the hell went wrong that turned this quite idyllic place into a battleground?

The North West Rebellion

The long story of the North West Rebellion can be found at this site on The Canadian Encyclopedia. The short story is that, despite the peaceful appearance of life at Batoche, things were not easy for either the Métis or the Indigenous peoples in the 1870’s and onward. The bison herds were gone, white settlers were pouring in armed with government grants of land, the railway was coming and a way of life was simply coming to an end. Like just about every group in history facing the same prospect, there were those who thought they could stop it and turn the clock back to happier times. Among those was Louis Riel, who returned from American exile in 1884 to first negotiate proper land title on behalf of his people. When that failed he formed a provisional government in Batoche and with Gabriel Dumont as military leader, commenced hostilities against the Dominion of Canada.

The first battle (really more of a skirmish) took place at Duck Lake where a dozen police officers and volunteers were killed along with a half dozen Métis, including Dumont’s brother, Isidore. The proverbial Rubicon had been crossed and there was no turning back for either side. Joining the rebellion were a number of Cree chiefs along with a few Assiniboia Sioux. The waters were further muddied by the capture of a number of Métis by Cree warriors, who then went on an indiscriminate killing spree. Needless to say, there was widespread panic in the west among white settlers, many of whom were beseiged at Fort Battleford.

The government reacted quickly, dispatching General Middleton and 900 troops by rail to Qu’Appelle from where they marched north to Batoche. Middleton was a career officer in the British Army and had fought Maoris in New Zealand and the Indian mutineers as well as serving in Burma, Malta and Gibraltar. He knew what he was doing and in hindsight the results were inevitable. After initial success at Fish Creek, the Métis forces were forced to retreat to Batoche where the decisive battle would be fought. There actually was no one great battle, but a series of engagements over three days. The Métis were expert marksmen and from the cover of firing pits were able to repel Middleton’s men until they basically ran out of ammunition and supplies and were overrun. The number of Métis killed during the three days of fighting is disputed, but it was significantly more than the eight Canadian soldiers who were slain. Dumont fled to Montana, but Riel surrendered.

Time now to walk the battlefield of Batoche

Walking the Batoche Battlefield

Anyone who has never walked a battlefield before will always be surprised at just how big an area most battles comprise. In paintings, the opposing forces are, by necessity, depicted as being cheek to jowl in a desperate lethal clash. The reality is, that in the age of the rifle and artillery, the killing takes place at great distances over vast swaths of territory. Batoche is no different, in fact the entire historic site is over 2,000 acres. During the summer there is a shuttle that takes visitors around to the various sites of importance. It’s a pleasant afternoon so Alison and I decide to walk instead.

We saw the first sign of the battle at the rectory where the guide pointed out bullet holes near the upper windows from where Métis snipers tried to repulse the advancing Canadians.

Several hundred yards away the land slopes down to steep banks on the South Saskatchewan River. General Middleton’s troops tried three times to advance up from the river, but were stopped each time at Mission Ridge.

Here is a replica of one of the firing pits which were so effective in both protecting the shooter and providing a vantage point from which to shoot down at the advancing soldiers.

General Middleton, now aware, that the Métis were not going to be conquered as easily as he had hoped came up with a novel idea to ensure the safety of his troops from the sharpshooters that were lurking seemingly everywhere. Borrowing a page from Africa, he constructed a zareba, which is a circular compound made from wooden posts, inside which he housed his men, horses and equipment when not engaged in battle. The walking path that leads us around Batoche takes us to the site of Middleton’s zareba.

Seeing the zareba being constructed must have been disheartening to the Métis as it made clear to them that the Canadians were not going anywhere until this matter was finished, one way or the other. The end came on the fourth day when two Canadian colonels, apparently without orders from Middleton, led their men on an all out assault on the Métis positions that led to their being overrun. The last major battle fought on Canadian soil was over, as was the North West Rebellion. The community of Batoche died as the Métis gradually dispersed. Today, no one lives here.

Batoche Cemetery

I find you can learn a lot by visiting the graves of those who died fighting in wars, and Batoche is no exception. These are the cemetery gates.

Nearby is this mass grave.

And this inscription. Note that two of the dead were English and that four were over fifty

This is the grave of Gabriel Dumont, who after 1885 went on to some celebrity as a wanted fugitive while at the same time appearing in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Later he returned to Canada and was allowed to live out his life in peace.

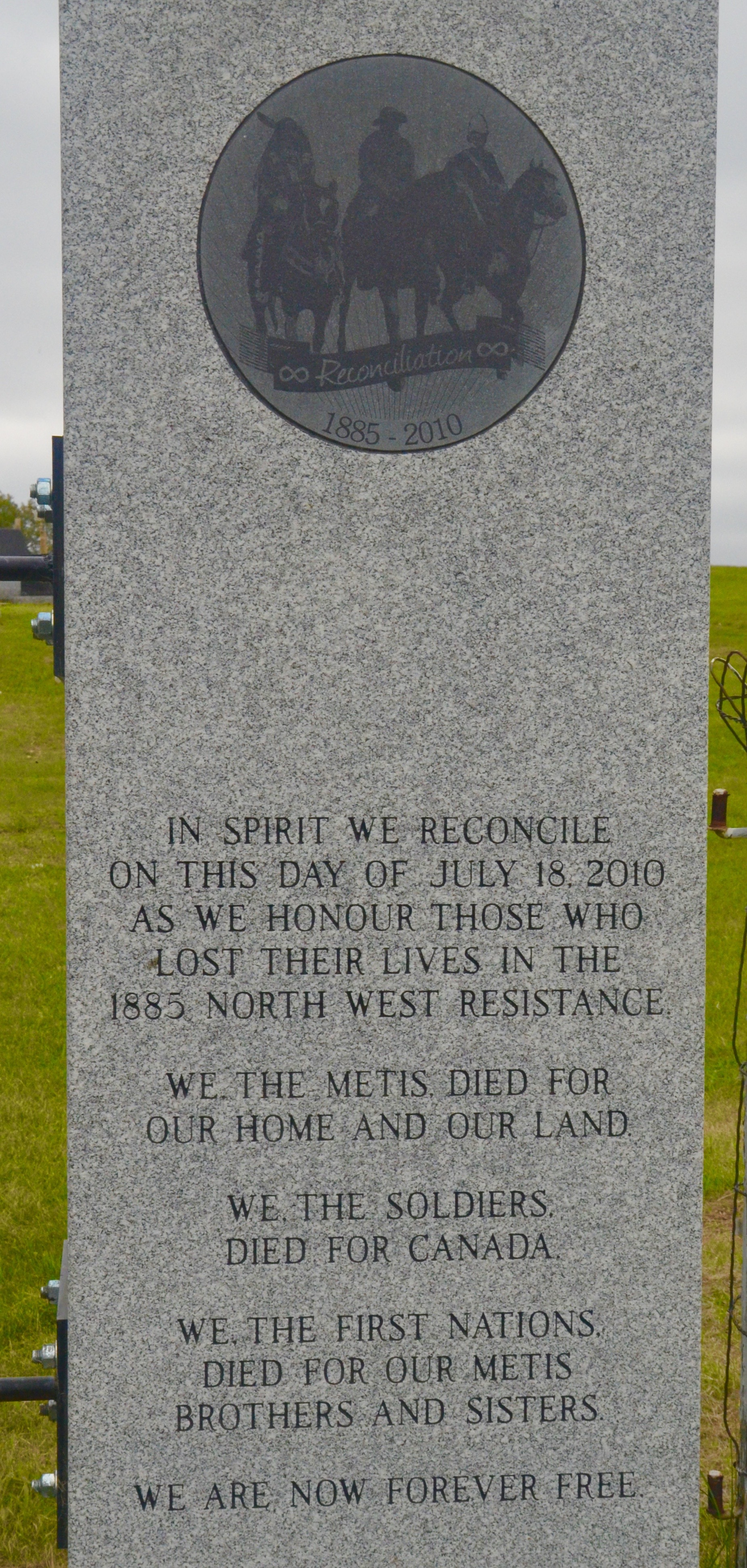

Also in the cemetery is this reconciliation monument that I think properly captures the essence of the North West Rebellion – there was no right and wrong side, and no heroes or villains. Each side was fighting for what they truly believed in.

After leaving the cemetery I followed a path that led down to an overlook of the river and came across this lone grave and wondered how this one young man was buried so far from home and why he was the only one of the Canadian forces left at Batoche. A little research revealed that he was the only Canadian soldier who’s body was not claimed by relatives and taken east for burial. There’s something terribly sad in that.

On the way back to the Interpretive Centre we came across this bison skull which I think is a perfect symbol of the Batoche – what it was, what it became and what it stands for today.

I said my goodbyes to Louis Riel, who ‘The Authorities’ would not forgive. He was hung as a traitor in Regina on November 16, 1885. We now know better. My reconciliation with Louis Riel and all he stood for and hoped to achieve, is complete.

For another side of surprising Saskatchewan read my posts on Grasslands National Park and the dinosaurs of Eastend. Our next stop will be in Saskatoon where we will visit sites related to John Diefenbaker, Saskatchewan’s only Canadian Prime Minister.

Here is a link to a photo gallery of our entire Saskatchewan trip.