Agira Canadian War Cemetery

This is the fifth and final post on the Canadian army’s efforts in WWII on Sicily to rid that island of its German occupiers. I am in Italy with my wife Alison, sister Anne and thirty-three other Canadians who are making a pilgrimage to pay homage to the Canadians who fought to liberate Italy during WWII and received next to no credit for their valiant efforts, despite the fact that almost 6,000 died. The tour has been organized by Liberation Tours, a Canadian company that specializes in taking Canadians to the places where our forefathers fought in WWI and WWII. In the previous post I wrote of the daring night time assault on Mount Assoro which is a great moment in Canadian military history. In this post I’ll focus on the end of the campaign in Sicily and conclude by visiting the Agira Canadian War Cemetery, where most of those Canadians who died in Sicily are buried. It promises to be a sobering afternoon.

Leonforte

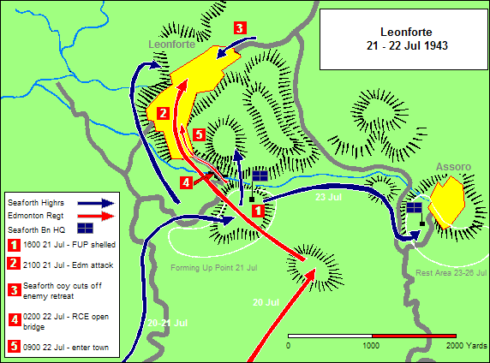

The assault on Mount Assoro coincided with the taking of the town of Leonforte by the Loyal Edmonton Regiment and the Seaforth Highlanders, that in some cases involved the first house to house fighting of the campaign. The PPCLI’s were busy on their own with German forces outside the town. Leonforte was a much larger town than Assoro that sat astride the main east-west road in Sicily. It also had a strategic river crossing that saw the Royal Canadian Engineers construct the first bailey bridge ever to be completed while under direct enemy fire.

The costs of taking Leonforte were high, with fifty-six Canadians killed and over one hundred wounded. The PPCLIs and the Loyal Eddies received Battle Honours, but strangely not the Seaforths, who had the most men killed. Unlike Assoro where no commendations were given, no less than twenty-one decorations were awarded for the Battle of Leonforte which only goes to show just how capricious these matters can be.

Our bus skirted the edge of Leonforte on the way to the next destination, Nissoria, which was the scene of more bitter fighting.

Nissoria

Nissoria was the next town after Leonforte on the main east/west Sicily road and not a hill top town like Assoro. This marked the end of the Canadian’s advance north from the southern coast. The orders, from General Montgomery himself, were to turn east along the highway and engage German forces entrenched around the base of Mount Etna. Just past Nissoria is the hilltop town of Agira which the Canadians fully expected to be strongly held by German forces. This is a view of Agira from atop Mount Assoro with Mount Etna in the background.

What the Canadians did not expect was to find the low lying town of Nissoria or its environs to be heavily defended. As you can see from the map, the Germans had three defensive lines between Nissoria and Agira – Lion, Tiger and Grizzly. Also from the map, you can see the numerous u-turns made by various Canadian regiments as they attacked and then were forced to retreat from these three lines. The Three Rivers Tank Regiment lost ten Sherman tanks while the HastyPs suffered the highest number of casualties by any unit during the entire Sicilian campaign, but they did secure the town of Nissoria.

We are now driving up the same road from Leonforte to Nissoria that the Canadians forces followed over seventy years ago. Today Nissoria is a town of just over 3,000 people without a lot to recommend it from a tourist’s point of view, but it does have one very good restaurant as we are about to find out.

This modern looking place is Ernesto’s Pizzeria where we are scheduled to have a nice sit down lunch, which in Sicily, is usually the biggest meal of the day. We are greeted at the door by Ernesto who has our tables prepared complete with local red and white wines. One of the great features of Liberation Tours is that they include many full meals at good restaurants with wine included.

We start of with antipasto, which really just means, before the pasta – petit fours and some really great stuffed olives. I’m quite pleased that a few at the table are not olive eaters, all the more for Alison and me.

Next is the prima platti which is always pasta, in this case, two different sauced varieties of what the Italians call macaroni, quite different than our version.

And then this crusted sea bass, which was excellent.

After the meal Ernesto thanked us, not only for patronizing his restaurant, but for what we had done as a nation to liberate his town.

After the toast Ernesto surprised us all with this beautiful cake, decorated in our honour.

What a great way to end the meal.

To say we were all full after this great meal would be an understatement. Before leaving Nissoria, the mayor came onto our bus and extended his heartfelt thanks to Canada for the sacrifice it made to liberate his town all those years ago. It was much appreciated.

Onward to Agira

After taking Nissoria the obstacle of the mountain town of Agira with its three fortified lines was next up for the Canadians. You can read the details of the battle here. It lasted three days and involved almost every Canadian regiment in Sicily at one stage or another. On July 28, the Germans evacuated Agira which definitely saved the town from a serious artillery bombardment that no doubt would have destroyed much of the historic town as well as killed many civilians. One of the terrible side effects of war is that ‘liberating’ armies often, intentionally or unintentionally, destroy some of the very cities and towns they are attempting to free, killing innocent civilians in the process. We will see more of that as we head to the mainland. However, I am glad that Agira, a town that was founded by the Greeks over 2,500 years ago, was not destroyed by us.

Battle Honours for Agira were presented to the following regiments – Three Rivers, Saskatoon Light Infantry, RCRs, Hasty Ps, 48th Highlanders, PPCLIs, the Seaforths and the Loyal Eddies.

In a somewhat ironic note, ancient Agira is now home to the largest outlet mall in southern Italy, Fashion Village, which hosts all of the top ‘designer’ brands. You can’t miss it on the outskirts of town. Why in hell anyone would want to drive into the Sicilian mountains to buy a pair of overpriced American jeans, is beyond me. Thank God this is not your usual bus tour or no doubt we would be herded here like sheep to be financially fleeced.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission

One of the most important aspects of the Liberation Tours trips are the visits to the cemeteries. They are usually at the end of the day and follow visits to the very places were the men interred, were killed. The visits are always solemn and very few people are dry eyed when it’s time to reboard the bus.

In the case of Sicily, all of the Canadians are buried in the one cemetery at Agira, but before visiting, first a few words about how the war cemeteries are maintained and administered.

The first thing to know is that almost all cemeteries containing the remains of soldiers who served from British Commonwealth countries in both wars are administered by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, an organization proportionately funded by the major members of the British Commonwealth. Great Britain pays 70% of the cost, while Canada pays 10%. Australia and New Zealand also contribute.

Believe it or not there are more than 23,000 cemeteries or memorials in 154 countries. Even more astonishing is that there are over 1.7 million men and women buried in them. I’ll repeat that – 1,700,000 war dead from the British Commonwealth in two world wars.

The Commission was first established in 1917 and laid down some early rules that are important. First, each of the dead must be commemorated by name if possible. Second, the headstones are permanent and will be maintained in perpetuity by the Commission. Third, all the headstones must be uniform. Fourth, no distinction can be made based on rank, race or creed. This is important, as in death, all are equal. A general gets no different a headstone than a private.

Also important is that every grave contains an actual body. Where the identity of the body is unknown it is indicated on the tombstone – that person becomes an unknown soldier.

Almost all the Commonwealth cemeteries are laid out in a uniform pattern. There is usually one entry through an archway or gated fence. You will always find two important documents inside a small metal container built into the side of the entryway. The first is the Memorial Register which is an alphabetical list of names with the necessary information to locate the grave. Most cemeteries are divided into sections and then rows starting with A at the front. So you find the section, the row and then the number.

You can prepare for your visit to any particular cemetery by looking it up online at the CWGC website. There you will find the names of every soldier interred in any particular cemetery and the specific site of the grave. Here is the site for Agira. I know a number of people on the tour have prepared their own lists of graves they wish to visit and honour and frankly, I’m regretting not having done the same.

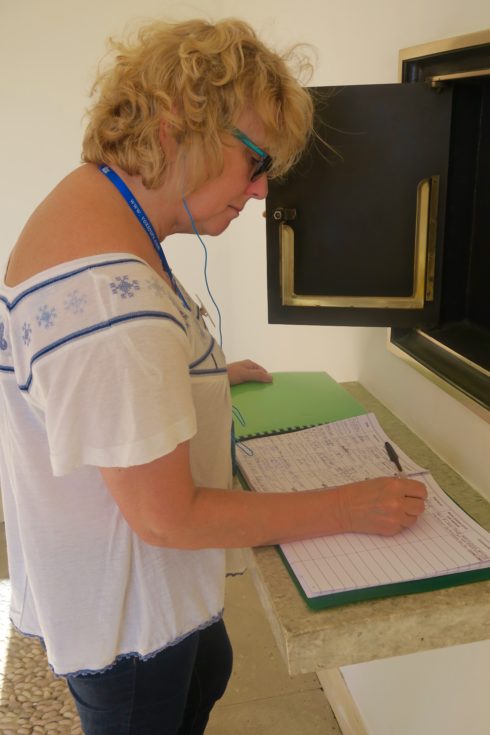

Before entering the cemetery proper there is another important book, the guest book. I think it is almost a duty to enter your name and address and any comments you wish to make. The fact that these boys and men are visited and remembered goes some small, very small, way to atone for the ultimate sacrifice they made. With these opening remarks, let’s visit the dead at Agira.

Agira Canadian War Cemetery

Agira Canadian War Cemetery has a beautiful location on the crest of a hill just outside the town. This is the view as you walk up from the very small parking area. Looking back you see the town of Agira.

On the other side of the crest is this view of Mount Etna.

The first stop is to open the Cemetery Register.

And then sign the guestbook. One thing is immediately apparent and that is the fact that the number of visitors here is minuscule compared to what you would find at a similar Canadian War Cemetery in France, Belgium or Holland. Another testament to the neglect that history has paid to these soldiers who gave their lives just a willingly as those on the Western front.

There are 490 Canadians buried at Agira, a substantial total of the 562 who died helping liberate Sicily. Time now to visit some of the graves. Let’s start with Lt. Earl John Christie. For some reason the CWGC only puts the initials of the deceased on the grave marker. I like to add the full name because I think it somehow gives a better idea of who the person actually was.

All Canadian graves, except those of the RCAF, are marked with the Maple Leaf. This contrasts with British graves which include the regimental badge. Most Canadian graves have a standard Christian cross although this was not mandatory. We will see other graves with no religious insignia, where the deceased was known to be an atheist or non-believer. Pretty ballsy in the 1940’s and proof that, yes, there are atheists in foxholes, but I digress.

At the bottom of the headstone the family was allowed so many letters to create a personalized tribute. Alternatively they could ask for a standardized phrase or nothing at all. Lt. Christie was the son of Archibald and Lydia Christie of Medicine Hat, Alberta. His personal eulogy reads,” In Memory of My Son, He Faced Destiny, As He Did Life, With Courage and a Smile”. Given the reference to ‘my son’ and not ‘our son’ I presume one of his parents predeceased him.

Lt. Christie’s story is quite unique. He was one of three University of Alberta students and friends headed into medicine, that joined up together and ended up in Sicily. Our tour historian Mark Zuehlke, author of Operation Husky, has written about Lt. Christie’s death in that book and here, before Christie’s grave, Mark relates it to us. This is a link to the story. Suffice it to say that Lt. Christie died on his first day in combat while his two companions survived many battles and lived to return to Canada. They both thought that Christie was the best of the three of them and had the most to offer as a prospective doctor. Such is death.

After relating the story of Lt. Christie, Mark frees us to roam the cemetery at our leisure, before returning to the bus for the trip back to Catania. Alison and I will specifically be looking for the graves of fellow Nova Scotians as others look for graves that are more pertinent to them. Before dispersing, John Cannon, the tour director, gives us four Canadian flags each which we can place on any graves we wish, either here or at any cemeteries we will be visiting on the tour. This is a really nice touch.

Agira is one of the nicest war cemeteries we have visited anywhere, not only because of its location, but also because of its tranquility. It’s absolutely quiet except for birdsong and the wind gently murmuring through the trees. The dead are truly resting in peace here.

Every CWGC with over forty graves has a monument called the Cross of Sacrifice which is the one constant from cemetery to cemetery. The inverted sword represents the fact that the soldiers buried here will fight no more. The one at Agira is particularly striking because it sits atop the apex of the hill and the graves slope away from it on all sides.

Here are some specific graves we visited and in some cases, planted the Canadian flag.

This is the grave of Lt. Colonel Bruce Albert Sutcliffe who, as far as I can tell, was the highest ranking Canadian killed in Sicily. I described his death by German artillery fire in the post on Mount Assoro.

As you can see from his photo he was a mature man, but what you can’t see was that he was a leader of men as well. Only three days before his death he carried out operations that led to a posthumous Distinguished Service Order. Here is a description of what he did to earn it.

On Saturday, 17 July 1943, this officer was ordered to move across unreconnoitred country a distance of 8 miles with his battalion and take the town of Valguarnera. He started with his normal complement on weapons but found the ground passable only on foot. He then continued without sp arms and led his battalion across most difficult country to ground overlooking the town. Here he made his plan and personally took a small party into the centre of the town meeting enemy vehicles and tractors; he led and directed close range attacks with S.A. and PIAT bombs destroying at least 6 large enemy transport – one gun, and killing upwards of 40 Germans. In the confused fighting which continued throughout the day Col. Sutcliffe kept together a small group of his men and hunted enemy snipers and M.Gs. throughout the day. One of his men moving close to him was severely hit by M.G. In the face of enemy fire this officer dressed the wound, got the man under cover and eventually in safety. His coolness, courage and determination in the face of enemy S.A., arty. and mortar fire were an inspiration to all his me, and were demonstrated also in an action before Grammichele on 15 July 1943 when under mortar fire he continued to direct the attack with great skill and courage.

At the other side of the spectrum, rank wise, is Private Aaron Sabblut, son of Mr. and Mrs. Hyman Sabblut of Vancouver, B.C. The Star of David identifies him as a practitioner of the Jewish faith, of whom a substantial number volunteered for service in WWII and many made the ultimate sacrifice. He was killed when his Bren carrier suffered a direct hit in Grammichele.

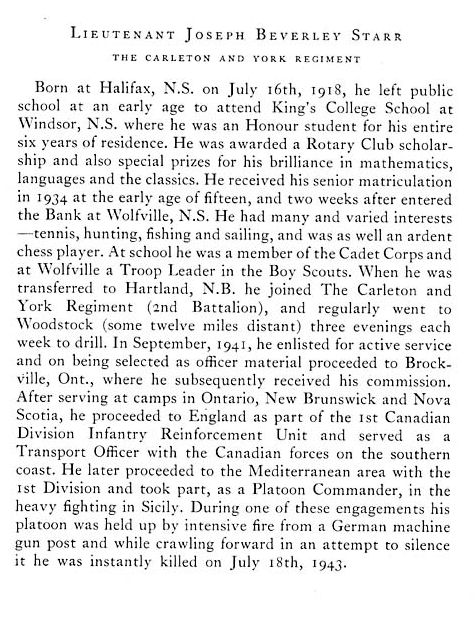

This grave is of double interest for me. Lt. Starr, son of Henry and Helen Starr, was from the same town as I was born in, Wolfville, Nova Scotia. He was a studious looking young man and his biography confirms that. It also explains why he ended up in the Carleton and Yorks from New Brunswick and not the West Novas. Another promising life cut short by war.

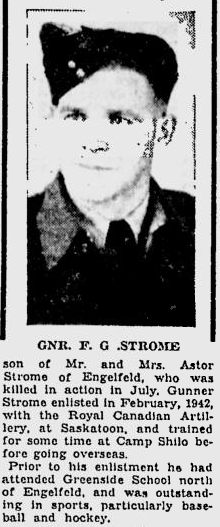

This is Gunner Frank Strome, son of Mr. and Mrs. Astor Strome, a farm boy from Engelfeld, Saskatchewan who died on July 21st, a terrible day for Canada that saw forty-one combat deaths.

Whether or not you can find out more information about any given individual on the internet, is a hit or miss proposition. I could find nothing about Pvt. Glode other than that he was born in Lunenburg, N.S. His grave attracted our attention because Glode is a Miq’maw name, and is another example of the diversity of Canadian troops during WWII.

This is another intriguing headstone. First of all D’Entremont is always spelled with an apostrophe, so technically the name is incorrect, something that does happen occasionally. It is one of the oldest family names in Nova Scotia and dates all the way back to the 1600’s. Secondly, he is described under the Casualty Records as the nephew of Mrs. Charles A. D’Eon of Upper West Pubnico, N.S., which begs the question, “Who were his parents?”. Finally, what was he doing with the Carleton and Yorks and not the West Novas? As it turns out both regiments were involved in the assault on Portello Crottocalda on July 18th and both regiments suffered numerous deaths, including Pvt. D’Entremont.

The 3rd Brigade sent the Royal 22nd Regiment to secure Portello Crottacalda, a narrow pass, while The Carleton and York Regiment and The West Nova Scotia Regiment moved to the flanks of the dominating high ground, a feature known as Monte Della Forma. The attack on this feature was supported by the divisional artillery, the machine guns and mortars of the Saskatoon Light Infantry, and tanks of The Three Rivers Regiment in extremely hot weather. By late afternoon, both units were on their objectives.

UPDATE: In June of 2019 I was contacted by Nigel Whiting, the grandson of Ken and Alice Billing of Northampton England. Ken was one of the electricians who connected Bletchley Park to the grid so that the secret code-breaking work that was going on there and was so important to the outcome of the war, could be started. They had a Canadian soldier billeted with them at the time – Frank. S. D’Entremont. Frank knitted a scarf with the Carleton & York crest on it and gave it to Nigel’s mother Marion and he has it to this day. He will be donating it to the 8th Hussars Museum in Sussex, New Brunswick which has a Carleton & York Regiment section.

He forwarded me this photo of Frank taken while he was staying with the Billing’s. He is the one on the left reading the newspaper. It’s always good to be able to put a face to the servicemen I feature in these posts. Thank you Nigel.

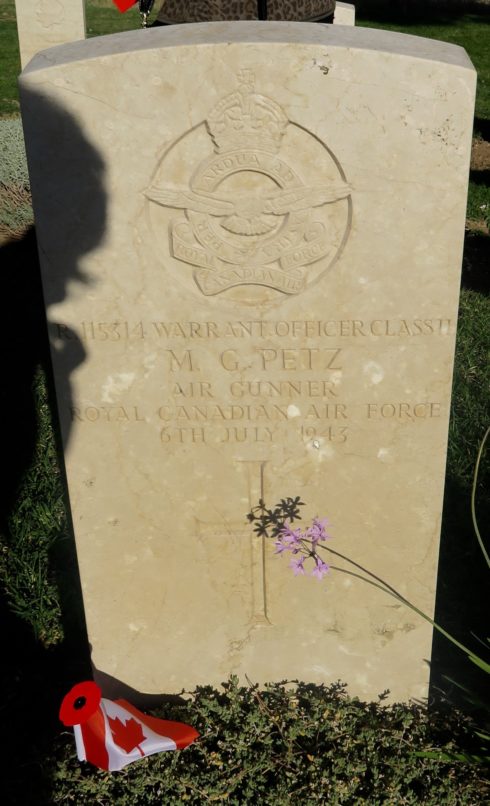

This is one of a few RCAF burials in Agira. The entire Sicily campaign was supported by air strikes launched from Malta and North Africa and casualties were high. WO Petz died on July 6, 1943 in a Wellington, while engaged in preliminary strikes before the July 10 landing. He was not a Canadian, but rather the son of Anton and Mary Petz of Chicago, Illinois. It was not unusual for Americans to join the Canadian armed forces, particularly the RCAF.

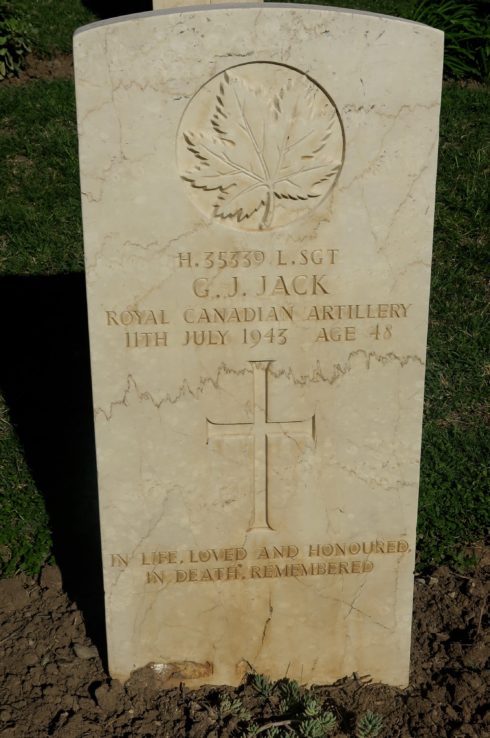

It was not just young men who fought in WWII. Lance Sgt. Jack was 48, son of George and Annie Jack and husband of Alice Irene. From the Winnipeg suburb of St. Vital, he very likely also served in WWI as did many of the ‘old timers’ in the Canadian army. He died a tragic death only the day after the landings on July 10 when he fell off a truck towing a large field piece and was crushed by the wheels of the towed cannon.

I could go on and on as every headstone has its own unique back story that, thanks to the internet, it is possible for anyone with a little patience to research. I urge anyone who visits a CWGC cemetery to do the same. However, it’s time to get on the bus and head back to Catania where our visit to Sicily will end and we will fly to Rome.

Our next stop will be in Anzio where will learn the history of the Devil’s Brigade, the only joint Canadian/American military unit ever deployed. Hope to see you there.