Kura Hulanda Museum – Curacao’s Dark Past

I bet if you asked people (well actually white Europeans or North Americans) which is the most liberal and fair nation on the planet, a lot of them would respond – Holland and the Dutch. I know I probably would based on my visits to that country and getting to know some of their fine citizens. But, if you asked the people of Curaçao and other Caribbean nations the same question, the answer for would be, for many, anyone but the Dutch. Even though Curaçao is intrinsically linked to modern day Holland and thus you might expect a relationship similar to what, say Canada has with Britain, I cannot believe that to be the case for anyone of African ancestry after visiting the Kura Hulanda Museum in Willemstad. Here’s why.

Coming to terms with history, especially history where one race or country has treated another abominably, is difficult to say the least. On the one hand the perpetrators must acknowledge the awful truth about their actions. That is not easy, as witness the current refusal of Turkey, Japan or even parts of United States to finally accept the documented truth of their despicable actions against other countries and ethnic minorities. How much harder must it be to come to terms with the fact that one’s ancestors were betrayed, often by their own leaders, kidnapped, sold into slavery and transported to a world they never wanted to be in? My ancestors came to North America because they wanted to and even though some were pressured by economic circumstances to leave, none arrived here in chains in the galley of a slave ship. These are the thoughts I am thinking after visiting the Kura Hulanda Museum and I don’t think that’s a bad thing. If humanity is going to make any progress going forward, we all need to try to get into each other’s skin and try to understand points of view and historical perspectives different from our own. I know that sounds clichéd, but aren’t we headed in the opposite direction where people have self-compartmentalized their sources of information so that they only get a reinforced view of their own beliefs and prejudices?

The day started pleasantly enough. My daughter Lenore and I flew into Curaçao yesterday and decided to spend day one on a walking tour of Willemstad, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. For over fifty years I’ve wanted to see its almost too good to be true harbour lined with those pretty pastel buildings from over two hundred years ago. And they do look great from Queen Emma bridge. The official walking tour of Willemstad, which you can pick up at the tourist booth right beside the Penha building on the right, actually starts on the opposite side of the harbour in the Otrobanda district.

Stop #2 on the walking tour is the Kura Hulanda Museum.

Kura Hulanda Museum

The Kura Hulanda Museum (don’t try looking for its website – you’ll be directed to an online pharmacy pushing viagra) is the brainchild of Jacob Gelt Dekker, a Dutch entrepreneur and self-made multi-millionaire. He has a penchant for delving into the type of matters I referred to above – coming to terms with history and moving towards reconciliation, if possible. To that end, in 1998 he convinced Curaçao authorities to let him restore a series of derelict, but very old, buildings on the then run-down Otrobanda district of Willemstad. Included in the plan was to create a museum dedicated to explaining to Curaçaons and tourists the history of the slave trade in which Curaçao played an outsized role in the Caribbean and South America. Sounds like a good idea right and it is, but Jacob was not going to sugar coat the brutal role that his Dutch forebears played in perpetrating what many believe is the single most evil event in human history – the forced diaspora of millions of native Africans from their homeland over a period of hundreds of years.

Museum admission is $10USD, but for $3 more you can get a guided tour which we opted for and joined a lone Dutch woman as the first group of the day just after the 9:00 opening.

The museum is actually divided into two distinct sections – the first is dedicated to the history of African slavery which is the focus of the guided tour and the second is an excellent collection, the best in the Caribbean allegedly, of African artifacts including masks, fetishes, bronzes, musical instruments etc. You can tour these at your leisure after the guided tour. Here are a few things you will see.

You can actually fool around with these.

There is also a small sculpture garden where you can see a collection of busts including these. After taking the guided tour you’ll understand why these people have such a look of despair.

A Guided Tour

Our tour guide was a tall, distinguished looking man named Rudolph and he first pointed out the large sculpture that dominates the central courtyard of the museum. From side on it looks like the face of a woman, but as you turn the corner it is revealed as a map of Africa – backwards in this photo.

Rudolph then began his explanation of the chronology of the African slave trade starting with Henry the Navigator who is considered by many to be the father of the Age of Exploration. Here’s one of the great ironies of history. At the time Henry was developing the caravel, the ship that made long distance exploration possible for Portugal and Spain, the Iberians were more the victims of slavery than its perpetrators. Their economy had no need for slaves, but the Moors across the Straits of Gibraltar, did and often raided Portuguese villages for slaves which were sold in Africa. Henry’s father was instrumental in the capture of Cueta, a centre of the Barbary slave trade and it remains a Spanish enclave on the coast of North Africa to this day. The irony is that Columbus and those that followed, used Henry’s ship design to ‘discover’ the New World and create an economy that was entirely dependent on slaves.

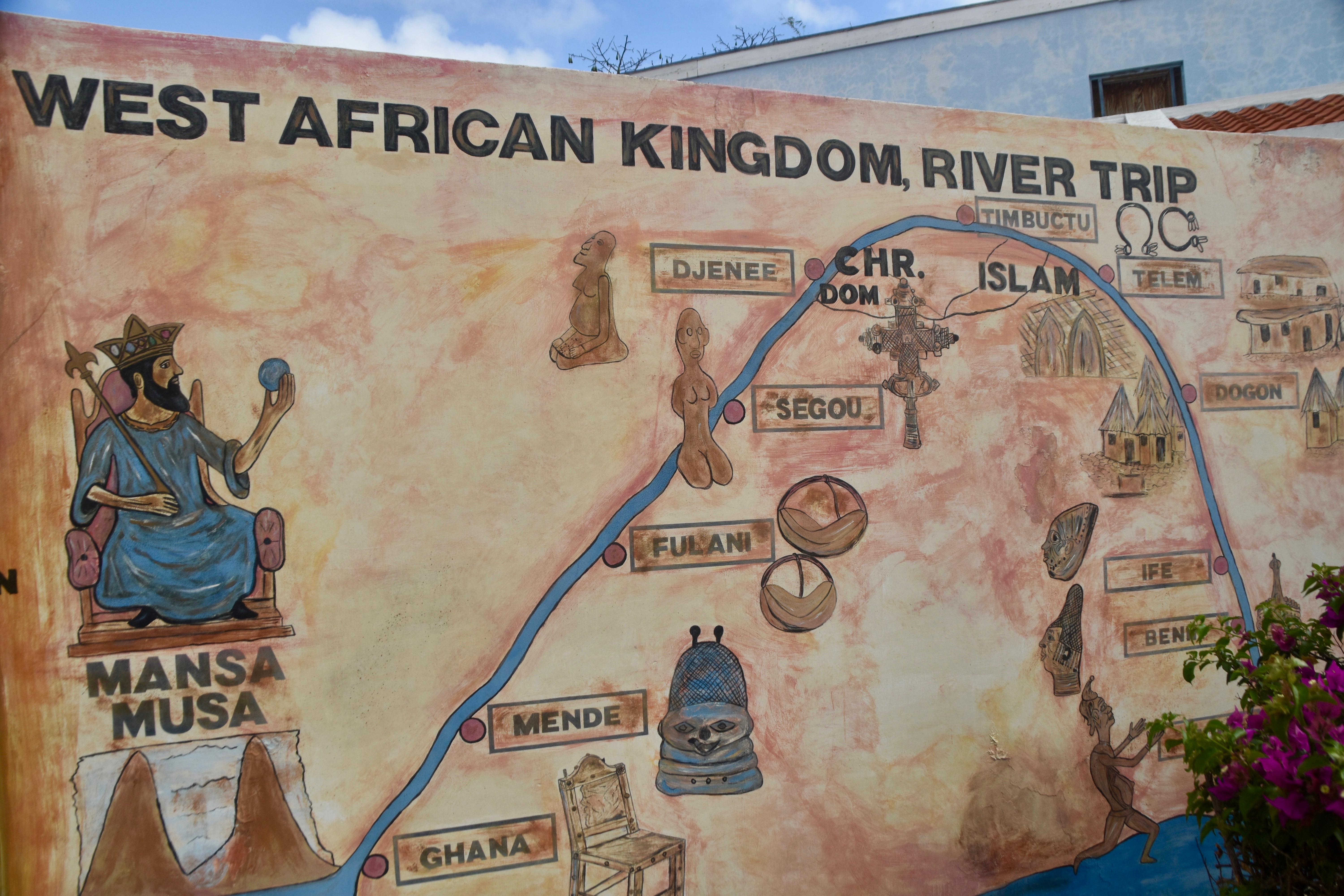

Here is a map depicting the area of West Africa from where the majority of African slaves were captured and eventually transported to the New World.

The next stop was under this bell which was rung to summon the slaves on a plantation, of which there were dozens in Curaçao, to witness the whipping of a disobedient slave. The slave was tied to one of the pillars and whipped 39 times, the number of lashes allegedly given to Jesus on orders of Pontius Pilate. After the flagellation a combination of vinegar, salt and other compounds was rubbed into the wounds. There are pictures inside the museum that show the horrendous scarring that results from this mal-medicinal treatment.

We now entered the interior of the museum which presented a real life chamber of horrors that once existed in Curaçao and throughout the Caribbean.

I grew up in northern Manitoba and immediately recognized these as traps which, in the fur trade, ranged from tiny ones for weasels all the way up to huge bear traps. Except these traps weren’t for animals, but for humans and the smallest ones were for children. Rudolph explained that the technique for ensnaring a large group of people was to catch a child first and the plaintiff cries would bring a group of villagers looking for the lost child. Once they arrived they were surrounded by the slave catchers, armed with superior weapons and it was no contest. Sadly, the slave catchers in interior Africa were usually other African tribesmen who then sold the captured people to Islamic and later European traders who would take them to the Atlantic coast for trans shipment to the New World.

The largest of debarkation points for African slaves was the infamous El Mina Castle in modern day Ghana.

Originally built by the Portuguese, El Mina was captured by the Dutch in 1637 which coincided nicely with their ousting of the Spanish from Curaçao three years earlier. This gave them both ends of the African slave trade and they really went to town over the next 170 years, exporting an average of 30,000 kidnapped Africans from the place every year. The last thing most Africans saw of their native country was the infamous ‘ Gate of no Return’.

I have been to El Mina and watched visiting Afro-American couples stand before it and literally break into sobs. It is one of the most harrowing and depressing places I’ve ever been and at the time I never gave much thought to the entrance gate at the other side, which was, more often than not, Curaçao – that is if they made it.

I think most people have seen representations of or read accounts of the conditions aboard these slave ships with the expression ‘packed in like sardines’ often applied. More likely it was the sardines that were packed in like slaves as this practice was far older than the canning of sardines. At the Kura Hulanda Museum Rudolph led us down a narrow ladder to the replica interior of a slave ship. This picture says all I could write about the conditions on board. There’s not just people on the top row, but underneath as well. Chained together they had to eat, sleep and defecate where they lay. The hold was washed out once a week.

So how were the slaves treated if they survived the two month plus trans-Atlantic journey? Could things get any worse? For some, yes.

I had recently visited the Spanish Inquisition New World headquarters in Cartagena, Colombia and saw an array of torture instruments that disgusted me. But I think the Dutch masters had them beat with this fiendish instrument of death. This is called a ‘tramp cage’, but it’s far worse. Tramp cages were used by American police in the 19th to humiliate and restrain prisoners. This thing in Kura Hulanda is far worse and much older. Rudolph stepped inside and shut the door and told us in a subdued, but ever increasing tone that runaway slaves were locked in these cages of iron, which is a great transmitter of heat, and left in the blazing sun until metal heated almost to the boiling point and the occupant died a horrible death.

Rudolph looked directly at the Dutch woman as he told this story and I could tell there was still some animus there, but how couldn’t there be? I asked Rudolph if this cage was actually used in Curaçao and he said it was built here and used many times. On occasion he said, if the occupant was not expiring quickly or painfully enough for the overseer or master, the cage would be suspended and a fire lit underneath to make the process even more gruesome.

Next he showed us this chest of dozens of leg irons, entangled together like brown snakes in a mating ball. My father used to buy ox shoes wherever he could find them and give them as presents to notable Nova Scotian geologists. They were not easy to come by. Apparently in Curaçao human shackles are much commoner than the shoddings of a beast of burden.

“Dutch masters” is usually not a pejorative term. One thinks of burghers dressed in black with ruffled collars looking out from the canvas of a Rembrandt painting or maybe a decent cigar. But after visiting the Kura Hulanda Museum, I will always think of the slave owners of Curaçao. To his credit, it was a modern Dutchman who insisted that the story be told. Thank you Jacob Gelt Dekker.

We came to Curacao primarily for the sun and water, particularly snorkeling, but ended up being as interested in the history of the island as its natural history.