Colonial National Historic Park, Virginia

When I was a boy there was a monthly event that I looked forward to with almost as great anticipation as Christmas morning – the arrival of the latest National Geographic magazine. I loved poring over the maps and looking at the pictures for which the magazine was justly famous. In 1960 National Geographic started publishing books, the first of which was America’s Wonderlands which featured United States’ National Parks. This was followed in 1962 by America’s Historylands which focused on National Historic Parks. I saved up my weekly allowance and bought both of these books, which I still have. They were a source of hours and hours of constant fascination and knowledge about magical places I would have to visit one day. It was from America’s Historylands that I first learned of a wonderful parkway in Virginia that connected two of the most important sites in American history – Jamestown and Yorktown. Collectively it was named Colonial National Historic Park, and in fulfillment of my promises to myself made over fifty years ago, I finally got to visit this spring. Here’s why it was worth the wait.

The Virginia Peninsula

The Virginia Peninsula which extends into Chespapeake Bay on either side of the James and York Rivers is, arguably, the most important piece of ground in the United States, at least from an historical perspective. It was here at Jamestown that the first permanent British colony in modern day United States was founded. And it was here at Yorktown that the American Revolution achieved success when the trapped British army surrendered to George Washington. In a sense one could say that the country began on the Virginia Peninsula not once, but twice. To top it off, the Virginia Peninsula is home to Williamsburg, the largest historic recreation in the United States and the third member of America’s ‘historic triangle’, but that’s for another post. Suffice it to say that there is more than enough on the Virginia Peninsula to keep anyone with an interest in history, occupied for days.

Colonial Parkway

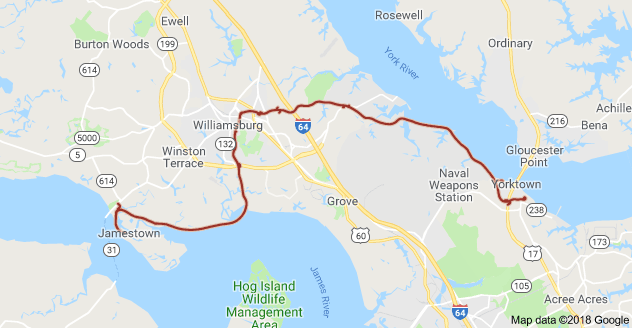

Although it’s only 23 miles (37 km.) long, the Colonial Parkway took over twenty-five years to complete. First conceived in 1930 as an appropriate way to connect Jamestown, Williamsburg and Yorktown, the Depression, WWII and occasional engineering challenges like the Colonial Parkway Tunnel caused numerous delays. It was finally opened in 1957 and now transports several million visitors a year. Given the popularity of Colonial National Historic Park, I would strongly advise visiting in the spring or late fall when the weather is still generally fine and the crowds are a fraction of what you’d find in the summer months.

From the map you can see that Williamsburg lies almost in the centre of the Colonial Parkway and that is where the vast majority of accommodations and restaurants are found. We stayed in one of the many chain motor hotels that are clustered near entrance to the parkway near the Colonial Williamsburg Visitors Center and found that getting on and off the parkway was quite simple.

Jamestown, Colonial National Historic Park

It makes sense to start your visit to Colonial National Historic Park by visiting Jamestown first, because after all, this is where it all began. The drive along the parkway is very pleasant as it passes through a typical Carolinian forest and then follows the north shore of the James River to the piece of land, once an island, that juts out out into the river and is the site of Jamestown.

However, before entering Jamestown proper, I strongly recommend visiting Jamestown Settlement which is very nearby. Run by the non-profit Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, Jamestown Settlement provides a detailed history of the colony with artifacts and mixed media, followed by recreations of a Powhatan village, Jamestown as it existed in the early 1600’s and full scale models of the three ships that brought the first settlers to the area. I was so impressed that I wrote this post just on Jamestown Settlement.

The visit to Jamestown Settlement should take at least two or three hours and you’ll come away much better prepared to understand and appreciate what you will see at the site that marks historic Jamestown.

Historic Jamestown is just down the road and frankly, after visiting Jamestown Settlement, one might be bit underwhelmed by what is actually on site. Admittedly, that was my first reaction, but once I accepted that Jamestown, which was effectively abandoned after the capitol was moved to Williamsburg in 1699, is now one giant archaeological site, then my initial disappointment evaporated. I’ve been visiting long abandoned cities around the world for decades and it was kind of neat to realize that this is exactly what Jamestown is today – only it’s not in Egypt, Greece or Italy, but right here in the United States.

The starting point is to try to get your bearings by looking at this model of early Jamestown, recognizing that none of what you see in this model is actually there, except the ruins of the brick church tower – that’s why you go to Jamestown Settlement first.

I mentioned earlier that Jamestown was effectively abandoned in 1699, however, what was abandoned then was a much larger settlement than existed in the early 17th century. One of things we did after visiting the principal sites of Jamestown was to walk the grid of the old town which had expanded to many times the size of the original settlement. In 1676 the entire settlement was burned to the ground during Bacon’s Rebellion so anything on site would post date that event. To make a long story short – by about 1800, no one had a clue as to the location of the original James Fort. The only structure on site was the ruined tower of the late 17th century brick church. as depicted in this old postcard.

This is an ongoing excavation underneath the foundation of the above church which was partially restored in the 1920’s. The story of how the site of the original James Fort was rediscovered and is now being excavated is a fascinating one. The Jamestown Rediscovery project was launched in 1994 by Dr. William Kelso with the aim of finding out if the original site of the fort had been eroded away by the James River as was the common belief, or if it still existed on dry land. Acting on an educated guess, he dug underneath the ruins of the brick church to find the remains of the first church and proved that Fort James was built right where I was standing while taking this picture.

As we walked historic Jamestown the car ferry that runs between Jamestown and Scotland (Virginia that is, not Great Britain) passed by these graves of unknown early settlers.

Pochahontas and Capt. John Smith

Chances are that many visitors to Jamestown have come with the expectation of seeing the places associated with Pochahontas and Captain John Smith. They won’t be disappointed. If you have visited Jamestown Settlement you will have a much better idea of what is fact and what is fiction. I won’t repeat it here, but suffice it to say that the Disneyfied version is completely inaccurate. Pochahontas was never romantically linked to John Smith, but rather John Rolfe. She did not stay in Virginia, but went to England with Rolfe where she died and is buried. However, she was a major historical figure in early American history and did play an important role in diffusing bad blood between the colonists and the Powhatans.

I suspect most visitors will definitely want to have their picture taken with the beautiful statue of Pochahontas at Jamestown.

Captain John Smith was the tough minded leader the early colonists needed to ensure the survival of Jamestown. He is not given enough credit for the explorations he conducted up the many rivers that flow into Chespapeake Bay that led directly to the establishment of many other communities in the area of Jamestown.

There is really something to be said for trodding the same ground that Pochahontas and John Smith did over four hundred years ago.

The Jamestown Archaearium, Colonial National Historic Park

At the far end of the Jamestown site is this ultra-modern building that houses the Jamestown Archaearium which houses more than 4,000 artifacts excavated from Jamestown. Do not overlook it.

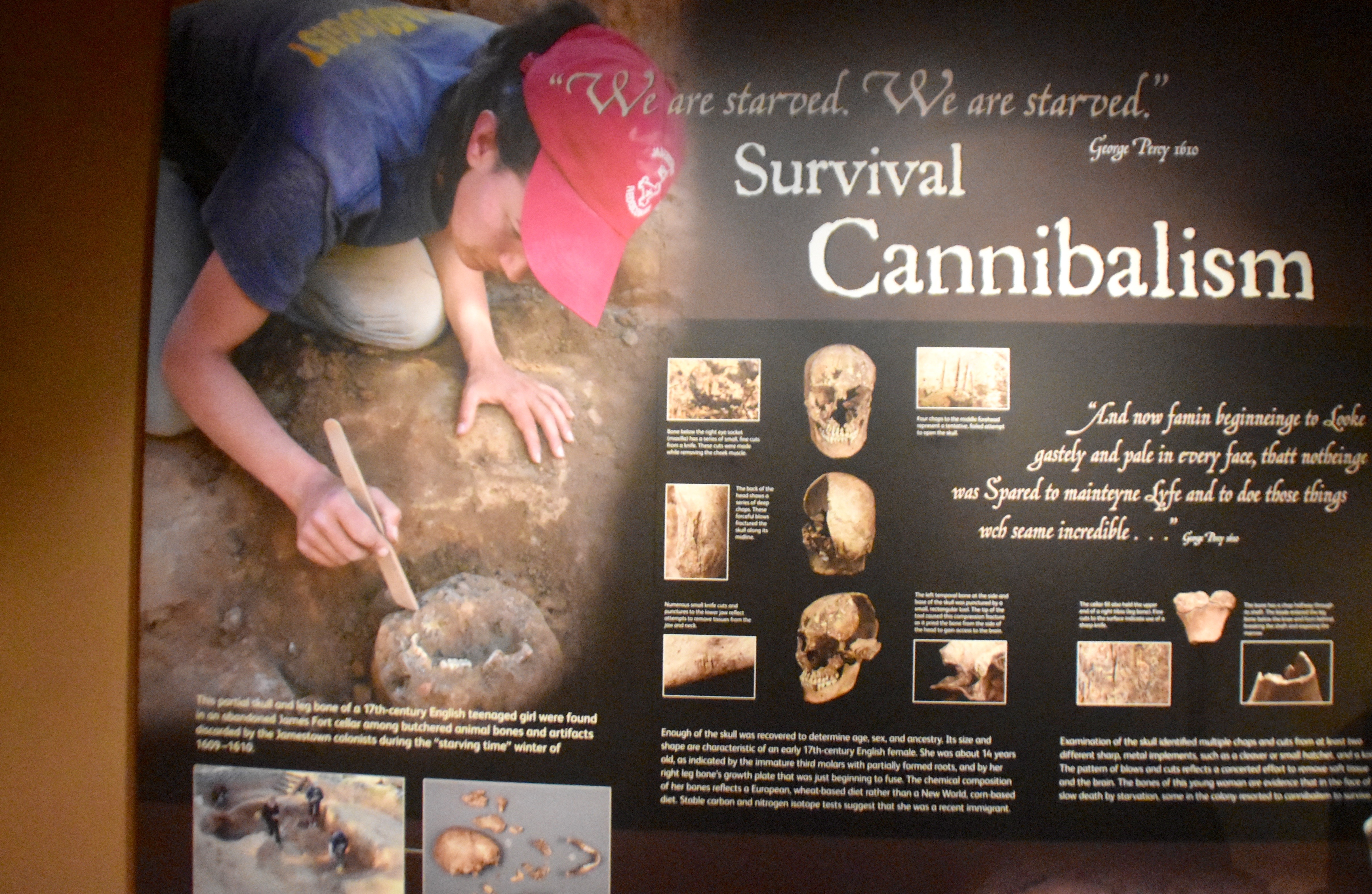

I found this particular exhibit to be both disturbing and understandable at the same time. Early in the history of Jamestown there was a period known as the ‘starving time’ when over 75% of the colonists died from disease and starvation. Excavation of this young woman’s skeleton revealed that she had been cannibalized after her death. The good news is that there is no evidence that anyone was killed to be eaten.

There is much more I could write about Jamestown including the fact that the first democratic assembly in America took place here, but it’s time to move ahead one hundred and seventy years to the siege of Yorktown.

Yorktown, Colonial National Historic Park

At the other end of Colonial National Historic Park lies Yorktown and another major turning point in American history. Driving from Jamestown to Yorktown you get the full Colonial Parkway experience, crossing over the Virginia Peninsula to the York River where there are numerous turnouts marking important locations in the lead up to Washington’s victory at Yorktown. There are also great views of the York River and you might even see a boat like this one that will remind you of the days of sail.

However, like Jamestown, there is one absolutely essential stop before entering Yorktown. That is the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown which is run by the same non-profit organization that operates Jamestown Settlement.

I cannot stress enough how much you will learn about the causes, battles and results of the American Revolution by visiting this facility that uses absolutely up to the minute technology and reenactors to tell the story. Please read my post on this great facility to get a better understanding as to why it is the perfect lead up to Yorktown.

The visit to Yorktown starts at the Interpretive Centre where we were pleasantly surprised to see a group of Union soldier reenactors camped nearby.

If you’ve gone to the American Revolution Museum it is unlikely you’ll learn anything new about Yorktown at the Interpretive Center, but it’s worth checking out for sure. After that, be certain to buy the CD with the Yorktown Battlefield Tour at the gift shop as this will make the battlefield tour 100% more enjoyable and understandable.

The Siege of Yorktown

The first thing to know about Yorktown is that is was not a battle per se like Saratoga or Trenton where the two armies faced off against each other. It was in fact a siege. The British army had managed to get itself trapped inside the town of Yorktown which they had surrounded with earthen and wooden fortifications. The second thing to know is that without help from the French it is unlikely Washington could have succeeded on his own. By this time in the revolution the French were all in on aiding the American cause. They had an army under the command of General Comte de Rochambeau and more importantly, the French fleet was blockading the York River to prevent a British evacuation as well as bombarding the British defenses from the river.

With this knowledge in mind, you follow the Battlefield Tour which starts in the Interpretive Center parking lot. The CD tells you when to stop and gives much more information than the interpretive panels at each stop. Here are just a few of the highlights.

This is the American Outer Line which essentially was where the siege began.

This is Redoubt 10 which was one of a number of British redoubts or small outer forts that had to be taken if the siege was to be successful. Under the command of legendary French hero the Marquis de Lafayette four hundred Americans armed only with bayonets stormed the redoubt in a night attack and after bloody hand-to-hand combat captured this vital position. Walking around the redoubt today, it is hard to imagine that this grassy knoll played just as important a role in American history as one would over 180 years later in Dallas.

Once Redoubt 10 fell Washington was able to bring his artillery right up to point blank range and the British knew their position was hopeless. Three days later General Cornwallis surrendered his army at this house, the Moore Homestead, and the American Revolution was effectively at an end.

Returning to the Colonial Parkway after completing the Yorktown Battlefield Tour we came across this sight which, although it was the wrong war, certainly helped bring history alive at Yorktown.

That concludes my tour of Colonial National Historic Park and I hope I have succeeded in convincing the reader to include it on your bucket list of great historic parks.