National Anthropology Museum – Mexico City

Mexico City’s National Anthropology Museum tells the story of the many cultures and civilizations that made up pre-Columbian Meso-America in both a compelling and readily understandable manner. It is simply one of the best museums in the world and no visit to Mexico City would be complete without spending at least a few hours here, although at least half a day would be better. Here’s why this should be your first stop before visiting the Templo Mayor.

Even those with the most rudimentary understanding of the pre-Columbian cultures of Mexico are familiar with the peoples commonly known as the Aztecs who populated the area around present day Mexico City and the Mayans of the Yucatan peninsula. But Mexico is a huge country with a paleo-history dating back tens of thousands of years. It stands to reason that there must have been many more peoples than just the Aztecs and Mayans and as this map in the National Anthropology Museum demonstrates there were dozens of other cultures throughout the land. A visit to the National Anthropology Museum will give one a much better understanding of each one of these peoples from the mother culture of the Olmecs to the dominance of the Aztecs that Hernán Cortés destroyed almost in the blink of an eye.

National Anthropology Museum – Practical Matters

Unless you are on a set tour of Mexico City or otherwise constrained, I cannot stress enough to give yourself enough time to visit the National Anthropology Museum. Allow a minimum of three hours, but four to five would be better. You can split it up by having lunch in between. Secondly, if at all possible, hire your own guide for a personalized tour. Our hotel retained forty year veteran guide Eduardo Castrejon Garcia for us. He picked us up in his car and took care of all arrangements with the museum including entry fees. Senor Garcia is a very knowledgeable and gentle man who’s English is very good compared to many of the guides that hold themselves out as fluent in English.

If you are visiting on your own then it is best to buy your ticket online which you can do here. The entrance fee for non-Mexicans is 70 pesos which is roughly $3.50 USD, a ridiculously cheap price for such a great attraction. The museum offers free guided tours in four languages (each tour is limited to the designated language of that particular tour), except on Sundays. They last up to two hours, but visit only two of the major rooms, usually the Mayans and the Aztecs. You can explore the other rooms at you leisure after the tour.

Do not be put off by warnings you might see on the internet that a number of the major exhibits are closed due to the earthquake damage suffered in 2017. While it is true that some rooms are still closed, like that of the Olmecs, the great majority are open and there is more than enough to keep one occupied for hours.

And don’t forget that like pretty well all museums in Mexico, it is closed on Mondays.

The Building

Many of collections in the National Anthropology Museum were in existence long before the current building was opened in 1964; as far back as 1790, the great German polymath Alexander von Humboldt visited what was then called the Cabinet of Curiosities. By the early 1960’s it was recognized that Mexico’s greatest treasures needed to be exhibited in one grand space and the great Mexican architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez was tasked with the design. Most people would agree that he succeeded beyond even the highest expectations, creating a building that has withstood the test of time that many buildings of the same era have not – just think Brutalism.

Coming from the parking lot or taxi drop off area you come to this entrance where there will probably be a line up, but it moves quite quickly and involves the now obligatory cursory bag search. I recommend just bringing your camera and leaving purses, backpacks and other items that will attract scrutiny, back at the hotel.

Mexico can compete with any country in the world for its long list of ‘don’ts’ at any particular attraction, but sometimes you see one you have been waiting for for years, like this. About friggin’ time and let’s hope it’s the start of a trend.

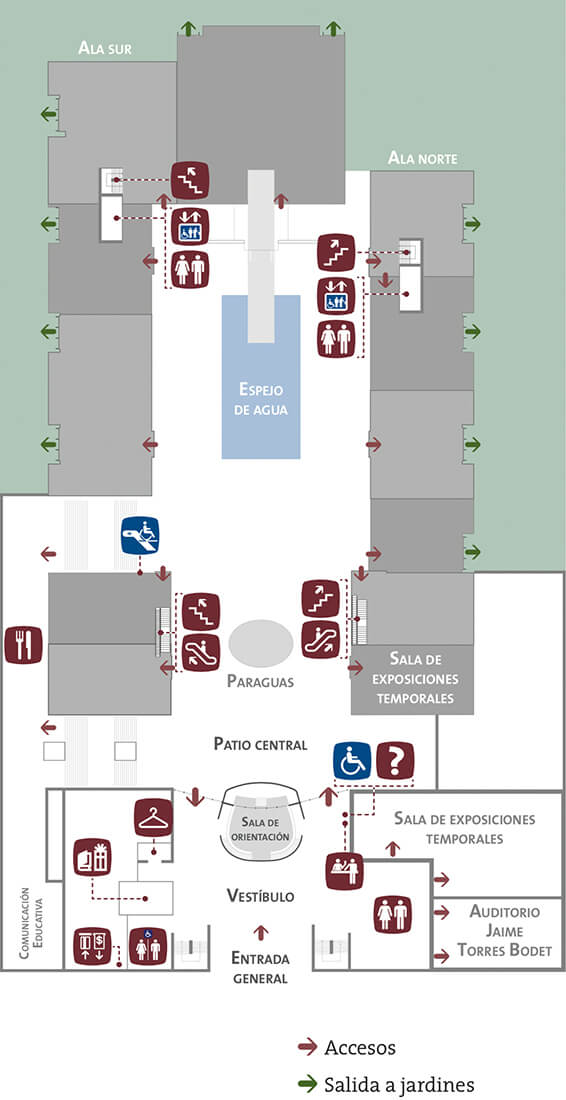

Here is a floor plan of the ground floor of the National Anthropology Museum, which is what 90% of visitors will confine their visit to.

The building is essentially U-shaped with a vast open space in between, but what an open space it is. This is the Paraguas or ‘Umbrella’ that greets visitors as they move from the ticket area to the museum proper. Water cascades down from this massive free standing column decorated with various symbols of pre-Columbian culture and a photo under it is almost obligatory for all first time visitors. Here I am with my sister Anne.

To really appreciate the beauty and sheer daring of the Paraguas you need to view it from the far side of the museum. It’s an entirely free-standing structure supported only by that one column.

The main galleries of the National Anthropological Museum are all on the ground floor and each features one of the major pre-Columbian cultures that thrived in Mexico prior to the arrival of the Spanish. They are not in chronological order, with the Aztecs or Mexicas occupying the largest gallery at the far end of the structure that connects the north and south sides of the museum. Apparently this, at one time, was somewhat controversial as it seemed, to some, to imply that the Aztec civilization was somehow superior than the others. However, touring the rooms, all of which have tremendous artifacts, this seems a bit of a stretch.

Settlement of the Americas

Most visitors tour the museum in a counter-clockwise direction, starting with the amazing first gallery showing how the country of Mexico was populated. However, it doesn’t just start with the movement of humans from Asia into the Western Hemisphere, but millions of years earlier with the evolution of the human species. I don’t recall seeing something similar anywhere. If you wanted to take a young person or maybe an evolution denier and show them how and why humans evolved to become the species we are today this is the place to do it. One could easily confine your visit just to this gallery and take in the various steps that had to occur to create a creature that was both sapient and collectively co-operative in a manner that sets us aside from all other species. Here’s just one example.

This one of many excellently done dioramas that show an important event along our path to becoming homo sapiens. The eating of meat, at first raw as at this stage, and eventually cooked, led directly to the development of a larger human brain. For more detail on why and how this happened read this article.

Here is another important step – the use of fire, not only to cook, but to keep warm as well. Notice that the creatures in this photo are much more human looking and less hairy than those in the first diorama. Fire led directly to evolution from maintaining heat through thick fur to the development of clothing.

There are many more of these dioramas and I could write an entire post just on this fascinating gallery, but I’ll end it with this very realistic depiction of a dead Neanderthal our closest relative, now long extinct.

As you leave this fascinating gallery you walk under this mural which depicts the populating of Mexico. It was the domestication of plants, corn in particular, that allowed the various peoples of Mexico to produce enough food to allow for specialization and urbanization. Notice the figures dancing underneath the stalk of corn.

Teotihuacan – National Anthropology Museum

The first civilization that is presented after the introductory gallery is that of the major city of Teotihuacan which thrived from AD 100 to about AD 700, when it was abandoned for reasons unknown. It lies only 50 kms. (30 miles) from Mexico City and is the most visited archaeological site in Mexico. Noted for the massive Pyramid of the Sun and Pyramid of the Moon, it once was home to at least 200,000 residents and like ancient Rome, had many distinct ethnic neighbourhoods. Not surprisingly, it has left behind a massive amount of artifacts, most of the best of which are housed in this museum.

This is a large scale model of Teotihuacan which is just outside the gallery proper. The largest building is the Pyramid of the Sun.

There is a smaller scale model inside which includes the lands surrounding Teotihuacan and this is where Eduardo explained to us the significance of the city in the history of Mexico.

What follows are photos of some of the more interesting items on display in the Teotihuacan gallery set out in the order that you would come across them.

Apropos of nothing is this display of what appear to be ancient vases. I was struck by how much the duck looks like current versions of bath tub toys – plus ça change …

On a more serious note, this is a recreation of a burial tomb found at Teotihuacan.

Contrast that to this final resting place of victims of human sacrifice at Teotihuacan.

This pleasant looking fellow is a devouring god that once adorned the Temple of Quezalcoatl.

This is one of the more famous artifacts in the National Anthropology Museum, the Disc of Mictlantecutli, Aztec God of the Dead. The strange thing is that this was found at Teotihuacan which was abandoned hundreds of years before the Aztecs were even on the radar and apparently dates from a millennium before the rise of the Aztecs. It goes to show that there is still an awful lot we don’t know about the connections between ancient Mexican cultures.

Perhaps the most interesting sight in the Teotihuacan gallery is the recreation of a side of the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, aka the Temple of Quetzalcoatl. This is what it would have looked like during Teotihuacan’s height.

Here is a close up of one of the fearsome heads guarding the pyramid.

This is Chalchiuhtlicue, Aztec goddess of water and like Mictlantcutli, found not at the Aztec capitol of Tenochitlan, but at the much older city of Teotihuacan. She’s a bit obese, coming in at over 20 tons and was excavated from under the Pyramid of the Moon, which it was believed might have been dedicated to her.

This is a collection of figures that all have prehensile arms and legs like modern dolls.

Near the end of the Teotihuacan gallery is this mural depicting the manner in which it is believed the pyramids of Meso-America were constructed. None of the pre-Columbian cultures in Meso-America made use of the wheel so that has led to a lot of conjecture about just how these massive monuments were actually built. I’m pretty sure this a more likely scenario than aliens.

When you are finished touring the Teotihuacan gallery there is only one thought in mind – you need to get your butt there asap to see it in person!

In between the Teotihuacan and Aztec galleries you pass by these rings that come from various places in Mexico where the Ball Game was played. This was a sacred tradition that was a part of life in every pre-Columbian culture including the Olmecs, Toltecs, Mayas and Aztecs. What is most interesting in this area is a video that shows just exactly how the game was played using only the hips to make contact with a very hard rubber ball (and I thought soccer was hard using only feet and head). There are quite a number of videos on You Tube showing the same thing, but none are as good or as clear as the one in the National Anthropological Museum. Make sure not to miss it in the rush to get to the Aztec gallery.

The Mexicas in the National Anthropological Museum

One thing I learned very quickly from Eduardo and others in Mexico City is that the people who I have been calling Aztecs for decades actually never used that term to describe themselves, but rather Mexicas (pronounced Me-shika) from whence the word Mexico. The term Aztec was apparently first applied by historian William Prescott in his 19th century History of the Conquest of Mexico and it stuck, at least until recently when many Indigenous groups have been reclaiming their proper names.

No matter what they are called, the people that occupied present day Mexico City when Hernán Cortés arrived in 1519 were among the most advanced in the world. Tenochtitlán, their capitol city, may have been the largest in existence at the time. Unfortunately they did not possess three things necessary to prevent the almost impossible to believe destruction of their empire in the blink of an historical eye – guns, horses and immunity to European borne diseases. What is on display in the Mexica gallery are some of the most significant archaeological finds in the world starting with this seminal piece which may be the most important one to Mexicans.

At first it doesn’t look like much until you study it closely and make out an eagle sitting on a prickly pear cactus holding a snake in its mouth. The cactus is on an island surrounded by water. Wait a minute, I’ve seen that somewhere before? Of course, the Mexican flag. This simple carving depicts the great foundation myth of the Mexicas. It is well documented that they were a nomadic people from the north of Mexico who believed that if they ever came to an island in a lake and saw an eagle sitting on a cactus with a snake in its mouth, then that is where they would stop and build a great city, which they actually did. Whether they ever really saw what they were supposed to may be open to doubt, but there can be no doubt that this artifact became the basis for the national symbol of Mexico. That’s pretty cool.

The next photo shows a cuauhxicalli in the shape of an ocelot (not a jaguar as I’ve seen in some descriptions). It is a vessel that goes to the very heart (pun intended) of what comes to mind when most people think of the Mexicas – human sacrifice. The hole in the middle of the back was used by priests to deposit human hearts that had been cut out of living victims, some of whom were children. There’s simply no way to put any kind of positive spin on this brutal practice and it backfired big time when the Spanish arrived because it gave them license, in their minds, to treat the Mexicas as brutally as they treated their own people.

And then there’s this guy. I can’t find out much about him, but I sure wouldn’t want him behind me in a line.

This is one of many representations of a jaguar that can be found in the National Anthropology Museums. All Meso-American cultures held this apex predator in high esteem.

As they also did with serpents. This is a very cleverly sculpted depiction of a coiled constrictor that oozes strength and reptilian avidity.

This is a close up of a portion of one of the most important artifacts in the Mexica gallery – the Wheel of Conquest. The Mexicas were real bastards to have as neighbours; they lived for war and conquest and by the time the Spanish arrived had enslaved or crushed pretty well all the other cultures in central Mexico. The Wheel of Conquest is a huge circular disk that is surrounded by panels like this one showing the Mexica chief on the left holding the head dress of his conquered opponent and pulling it down in submission. Other panels show the conquered chief with spears through him or other methods of subjugation.

But, as the saying goes, “What goes around comes around” and it did in spades for the Mexicas when the Spanish arrived and added them to their wheel of conquest.

At this point you will be approaching the star attraction of the National Anthropology Museum, the Sun Stone, which is first seen in alignment with the Moon Goddess Coyolxauhqui, pictured in the foreground. In Mexica mythology she was murdered by her brother Huitzilopochtli, the insatiable God of War and chief deity of the Mexicas.

This is the famous Sun Stone which was found under the Zocalo or main plaza of Mexico City in 1790 and for many years believed, mistakenly, to be a calendar. It is now believed to have been used as, what else, a sacrificial altar. Surprisingly, it was carved only a few years before the Spanish arrived and as Eduardo pointed out, by looking behind it, the sculpture was never completely finished. It weighs 24 tons and is a massive and quite majestic work which can’t help but impress even the most well traveled of museum goers. We noticed that every Mexican visitor wanted to get their picture taken with the Sun Stone and it took some patience to be able to get this photo with no one else in the picture, but it was worth the wait.

After visiting the Sun Stone there is a collection of carved personages starting with the Snake Queen Cōātlīcue, the mother goddess of the Mexicas. Isn’t she a knockout?

Nearby are a number of smaller images of her priests, dressed in these enormous head dresses that must have impressed the hell out of the everyday Mexicas.

This handsome fellow is Xochipilli who, despite the rather tortured look on his face, was the god of love, music and song. He was also an eater of magic mushrooms with which his body is imprinted in a number of places if you look closely. So the look is actually one of being completely stoned. BTW Xochipilli is the guy on the left.

Zapotec, Olmec and Maya Galleries

I have to confess that by now Alison and I were starting to get a bit flagged having been at this for a number of hours and hardly anywhere near finished with the major galleries. We asked Eduardo to just show us the highlights of the remaining galleries that were open starting with the Zapotecs of the Oaxaca region south of Mexico City.

This is a jade mask which was completely different from anything we saw in the previous galleries. It represents the Zapotec Bat God Zotz and was found at Monte Alban, a site we will be visiting on this tour.

Also of note in the Zapotec gallery was this recreation of Tomb 104 from the city of Monte Alban. What is interesting about this tomb and others at the site is that these are not burials of Zapotec people who built Monte Alban, but rather the much later Mixtecs who re-used the graves long after the city was abandoned by the Zapotecs.

The Olmecs were the first great Meso – American civilization and the foundation culture for all that were to follow. Unfortunately the Olmec gallery was still closed because of earthquake damage, but we still got to see one of the giant heads for which the Olmecs are justly famed. However, this was from over 100 feet away so it was difficult to get a perspective on just how large these heads really are. Another reason to return.

Likewise large parts of the Maya gallery were still off limits, but not the recreation of the tomb of King Pakal discovered in Palenque in 1952 by Alberto Ruz in manner not unlike that portrayed in Indiana Jones movies. This was literally the Mayan equivalent of King Tut’s tomb. I was amazed at the similarity of the huge sarcophagus buried beneath a pyramid to those we had seen at Giza.

Eduardo pointed out one final detail that caught the eye of the first Spanish explorers in the Mayan regions. If you look closely you can make out the outline of an elaborate cross. The Mayans did venerate the cross as a symbol, but it had nothing to do with the Christian idea of the cross as a symbol of Jesus’ crucifixion. It’s another example, just like the pyramids, of ideas that arise independently in different cultures and civilizations at different times.

That concludes my tour of the National Anthropology Museum for now. I hope to return in the near future to tour the second floor which features contemporary Mexican peoples.

In the next few months I’ll be writing about visits to Tenochtitlan, Teotihuacan, Monte Alban and other pre-Columbian sites. I hope you’ll join me.