Scottish National Portrait Gallery – Outstanding

I was on a recent tour of Great Britain with Canadian military travel specialists Liberation Tours and we had arrived in Scotland after an exceptional and jam packed romp through England. It was time for a break and we had a free day to explore Edinburgh on our own. Most in the group opted for a visit to Edinburgh Castle, but Alison and I and my sister Anne had been there a number of times before. Instead we decided to check out the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and it turned out to be a great decision. Here’s why.

History of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery

Population wise Scotland is a tiny country compared to England, France or Germany and yet during the 18th and 19th century it produced a tremendous number of absolutely outstanding figures in almost any field of endeavour one cares to name. The Scottish Enlightenment, as it came to be known changed not only Scotland, but the entire world. In preparation for this visit I had listened to Arthur Herman’s well received best seller How the Scots Invented the Modern World and had, I hoped, a decent appreciation of many of the figures I expected to see at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

By the late 1800’s the Scots were well aware of the significant role they had played on the world stage over the previous two centuries and decided to build the world’s first art gallery dedicated solely to portraiture of a nation’s great figures. The idea caught on and now there are many national portrait galleries, but once again the Scots were first with a great idea.

The building that houses the Scottish National Portrait Gallery is a work of art in and of itself, a magnificent red sandstone art palace designed by Sir Robert Rowan Anderson, one of the great Victorian architects of the day. It opened in 1889 and has been welcoming visitors ever since.

Admission to the Scottish National Portrait Gallery is free and on the day we visited, almost completely deserted. I contrasted this to my last visit to Edinburgh Castle when there were so many tour groups going through in so many languages that it sounded like the Tower of Babel with a touch of the Tokyo subway system thrown in.

Scottish National Portrait Gallery Entrance

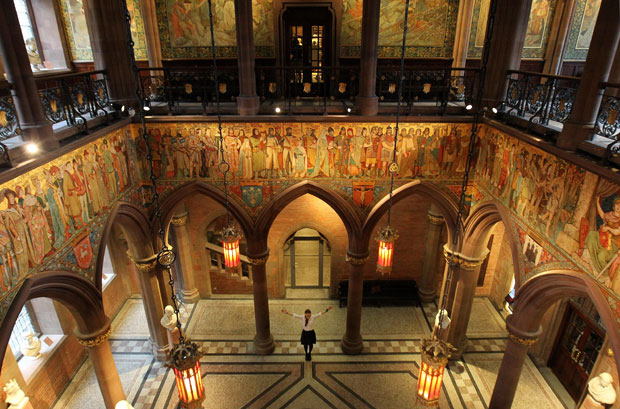

To say that the first impression of the interior of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery is stunning is not to indulge in hyperbole. There is a massive three story neo-Gothic atrium that is surrounded with murals, friezes, sculptures and busts of Scottish greats and great events. Being the idiot I am, I did not have a proper flash or a wide angle lens to do justice to this overwhelming entrance so I have borrowed some public domain photos to assist.

This is the ground floor with a full size statute of Scotland’s most beloved son, Robert Burns taking centre stage. I had to have my picture taken with him, as we share common antecedents in Ayrshire.

Alison also sought out one of her potential forebears, Sir Walter Scott, the only other one who could give Burns a run for his money in terms of literary fame.

Walking up the wide stairways to the second level you get this view.

From the upper floor you get a better view of the great Proccessional Frieze by William Brassey Hole . This is my photo of one side.

However, if you follow this link from the museum’s website you can get a much closer look at all four sides and zero in on any particular character. We spent a good half hour just walking around the upper floor identifying one great Scot after another.

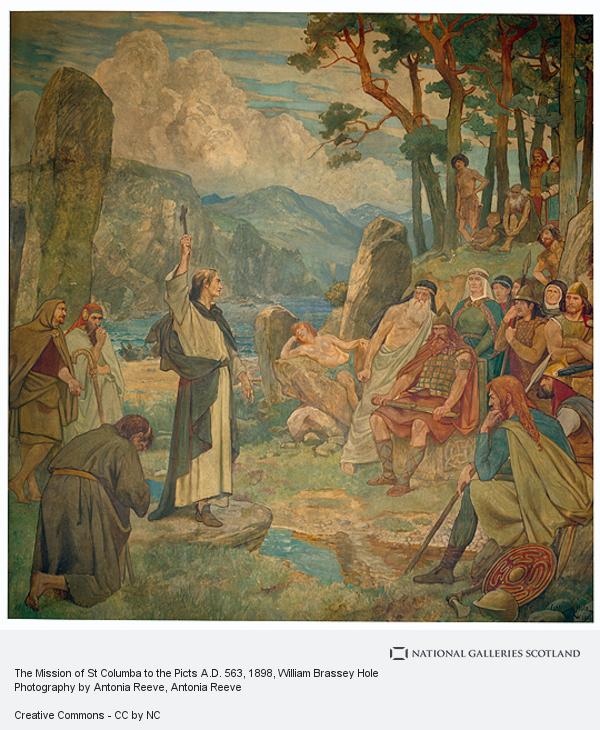

On the walls of the upper floor are a series of murals by Hole depicting famous events in Scottish history in the style favoured in the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. I happen to like this style very much and you can see examples of it in the great Canadian railway hotels built around the same time. This is St. Columba’s Mission to the Picts in A.D. 563.

Others include The Landing of St. Margaret at Queensferry in A.D. 1068, The Good Deeds of King David II and the massive The Defeat of Hako King of Norway by Alexander III at Largs.

There is sense of grandeur to the entrance way to the Scottish Natural Portrait Gallery that I have seldom seen equalled and if that was all there was to see it would be worth the visit on its own. However there is much more. Like the lower floor, the upper floor has on display many busts of famous Scots including this one of a person I doubt you’ve heard of.

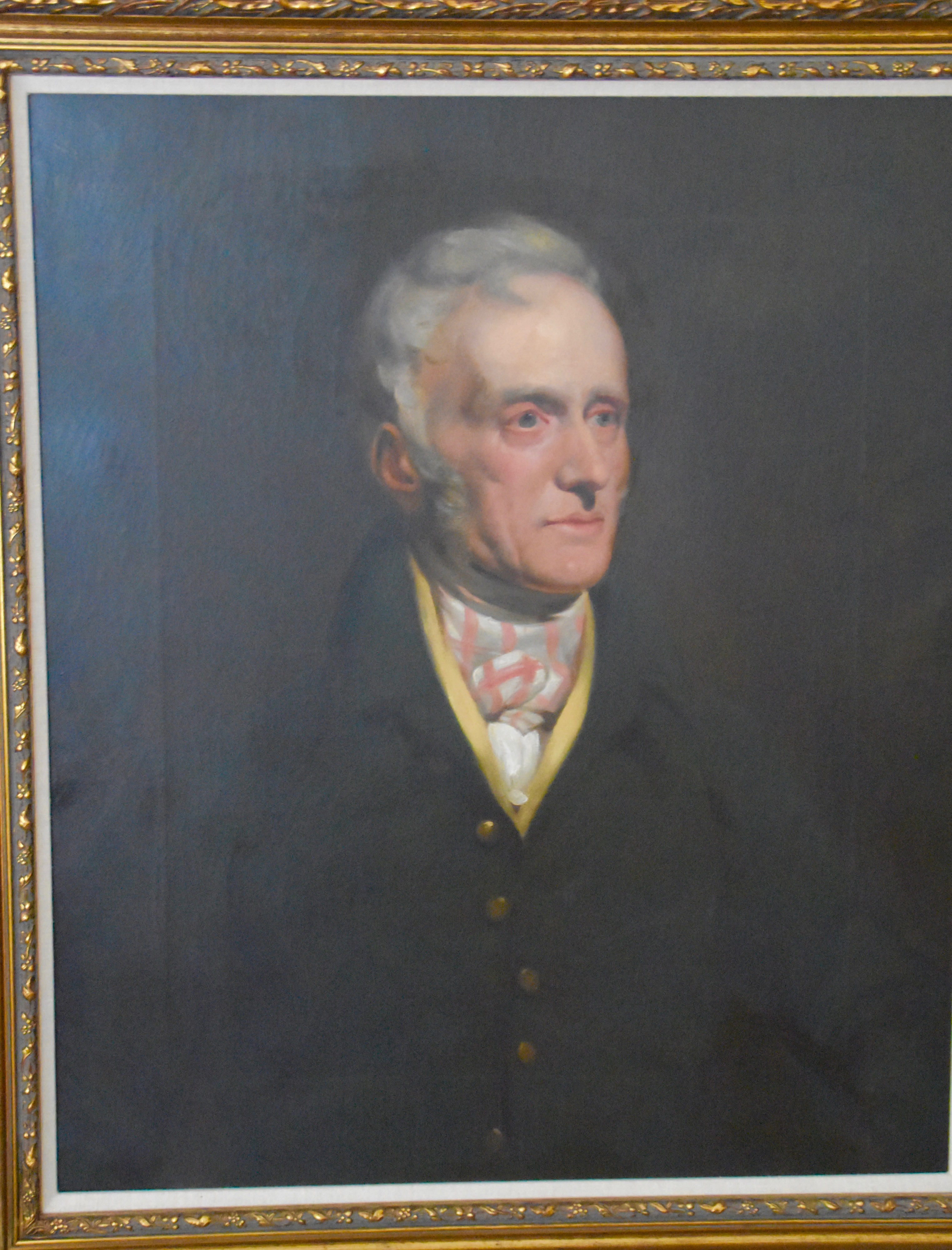

This is Sir John Watson Gordon, a student of Raeburn’s, who is considered one of the great portraitists of his time. If you follow the link you will find paintings of Sir Walter Scott, the great historian MacCaulay, author Thomas de Quincey and many others. I have an affinity for Gordon for a special reason. Almost fifty years ago as a teenager I was at an auction in Winnipeg and an extremely well done portrait of an unknown man by an unknown artist came up for sale. I managed to convince my mother to lend me the $100.00 I paid for it. Later, having it removed from the frame the name of the artist and sitter were revealed.

This is Baronet Sir Alexander Charles Gibson-Maitland by Sir James Watson Gordon and it hangs in my living room today.

The Historical Gallery

After pulling oneself away from the grand entranceway the next stop is the beginning of the historical portrait section on the second floor. This is perhaps what most people have in mind when they think of a portrait gallery – pictures of famous dead people. Sounds kind of boring, except at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery it’s not. The gallery uses the portraits to tell the story of the history of Scotland from the time of Mary Queen of Scots to the present day in a straightforward chronological sequence that will leave the viewer with a much better understanding of Scottish history than before visiting. Instead of just putting up the name of the subject and the painter, each portrait is accompanied by much more detailed explanations of the life and times of that person. In other words, there is a context to this gallery that makes it much more than just a bunch of old oil paintings. So let’s get started. I have included photos of the portraits I found most interesting, both for the subjects and the quality of the portrait.

Most people think of Mary Queen of Scots as a failed aspirant to the English crown and such a thorn in the side to Queen Elizabeth I that she eventually had her beheaded. Perhaps no figure in history has had more bad historical novels (and a few good ones) written about her than this infamously mercurial woman. However, before she was forced to flee from Scotland by the Protestant Congregationalists she ruled Scotland for a full twenty-five years. She also got the last laugh on Elizabeth by having her son James declared King of England after Elizabeth’s death.

This portrait of her by an unknown artiest was painted during her period of captivity in England and is considered one of the best of many representations of her done while she was in the clutches of Elizabeth. Note the Catholic regalia with which she is adorned, which is what got her into trouble in the first place.

Not all of the portraits are of famous historical characters. This is Tom Derry by Marcus Gheeraerts, the Younger who did much more famous portraits of Elizabeth I, the Earl of Essex, Queen Anne of Denmark, James I wife and Sir Francis Drake, but I don’t think any of them are as good as this one. He is described as being a ‘natural fool’ which, believe it or not, is an actual legal term signifying someone who looks normal, but is incapable of managing their own affairs. In Tom Derry’s case he was put to work as a jester in James I court and no doubt would have been the subject of many laughs at his expense. However, apparently Queen Anne of Denmark doted upon him and commissioned this portrait by a then very well known and expensive artist.

There are numerous portraits from the early Stuart years culminating with this gory, but fascinating painting of the execution of Charles I by an unknown Dutch artist. The execution took place outside the Banqueting Hall in Whitehall, London on January 30, 1649. The painting is not accurate in that the executioner’s face was covered by a mask, but is accurate that people fainted and groaned. The execution of a king by his subjects was a virtually unprecedented event in European history and only after the deed was done did the gravity of the event sink in for many. From the moment Charle’s head was severed, Oliver Cromwell was on the defensive and it could be said that this regicide sowed the seeds for the restoration of the monarchy only eleven years later.

While not a great painting by any means, this is still a very important historical work.

Usually portraitists do their best to flatter the subjects who pay them, but sometimes the person is so inherently bad looking both in appearance and demeanour that it is impossible to disguise and such is the case with David Scougall’s portrait of Archibald Campbell, Marquess of Argyll. Campbell was the leader of the Covenanters who were almost fanatic Presbyterians in the mold created by John Knox. They were constantly at odds with the Catholic Stuarts and Campbell was known for his guile and willingness to betray his friends if it would help him personally. One example was his cooperation with Cromwell followed by support for the restoration of Charles II to the throne once Cromwell was ousted. He even placed the Crown of Scotland on Charles’ head at Scone. It didn’t work. Charles II had him tried for treason and he was beheaded in 1661.

The next paintings focus on the time of the Restoration which saw the reigns of Charles II, James II, the husband and wife team of William & Mary and ending with the last Stuart, Queen Anne. Here is my sister Anne with Jan van der Vaardt’s portrait of Queen Anne. Although pregnant eighteen times, she had only one child survive infancy and he died as a child. That doomed the Stuart’s and led to the Act of Settlement of 1701 which defined future provisions for the selection of British monarchs. That act also contained an unusual provision that has relevance today because of someone who apparently thinks he is a king. From 1701 onward no persons convicted or impeached by Parliament could be pardoned by the reigning monarch. Strangely enough, the new Americans who had just successfully gotten rid of the king’s dominion in 1783, incorporated the power of Presidential pardon in their new constitution. One has to wonder, given the British precedent which the framers of the Constitution would no doubt have been aware of, just what the hell they were thinking.

No visit to the Scottish National Portrait Gallery would be complete without gazing upon the eminence of one of the biggest phonies and failures in Scottish history – good old Bonnie Prince Charlie. This is but one of many portraits and busts of Charles Edward Stuart, grandson of James II in the gallery and in fact if you go online you’ll find so many different portraits of him that he must have had little time to do anything else, but pose. And poseur he most certainly was. Leading his troops from behind at the disastrous Battle of Culloden he ran away and eventually slunk back to continental Europe where he lived out his days as a foppish womanizer. However, he was always a good Catholic, so much so that he is buried in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome along with countless Popes.

I guess you can tell that I don’t like this guy and am amazed at the romantic traditions that have grown up around this unabashed failure.

There is one more portrait from the historical period and I think it is the best from this era. This is Patrick Grant as painted by Colvin Smith in 1822 and it has a remarkable story behind it. Grant was a veteran of Culloden and was over 100 years old when he was introduced to King George IV on a visit to Scotland, as “Your Majesty’s oldest enemy”. George was so impressed that he granted the old man a pension and had this portrait commissioned. The picture has a mix of quiet dignity and rueful reflection that captures the essence of a veteran with perfection.

Moving forward, the portraits take a decided turn away from royal and military figures and start to feature the individuals that made Scotland famous for its learning, enterprise and inventiveness. This is the famous journalist and first modern biographer James Boswell by artist George Willison. One has to wonder why he painted Boswell with a couple of buttons on his vest open, giving an impression of corpulence. Boswell’s Life of Johnson is considered one of the greatest biographies ever written, but of equal interest to me is his lesser known Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides which describes a trip with the irascible Samuel Johnson to what was then a pretty wild place from whence, around the same time, many were leaving for my province of Nova Scotia.

Perhaps no figure in Scottish history was more influential than the philosopher David Hume portrayed here by the best known of Scottish portraitists Allan Ramsay. He might rightly be deemed the father of the Scottish Enlightenment and the influence of his ideas resonates right up to the 21st century. Ramsay has given him a cryptic smile that could be either a look of condescending dismissal for the mere mortal staring at this great man or it could be kindly beneficence, reflecting the great ideas that he bequeathed to his fellow man. That’s the mark of a great portrait – it makes you not just gaze upon a countenance, but think about the person portrayed.

The viewing continues past portraits of Robbie Burns, a young Queen Victoria, two famous Stevenson’s, engineer and lighthouse builder extraordinaire Robert and his writer son Robert Louis, James Watt, the inventor of the steam engine and one of the greatest Prime Ministers in British history, William Ewart Gladstone. This post would never end if I focused on each one although all are worthy of seeing in person.

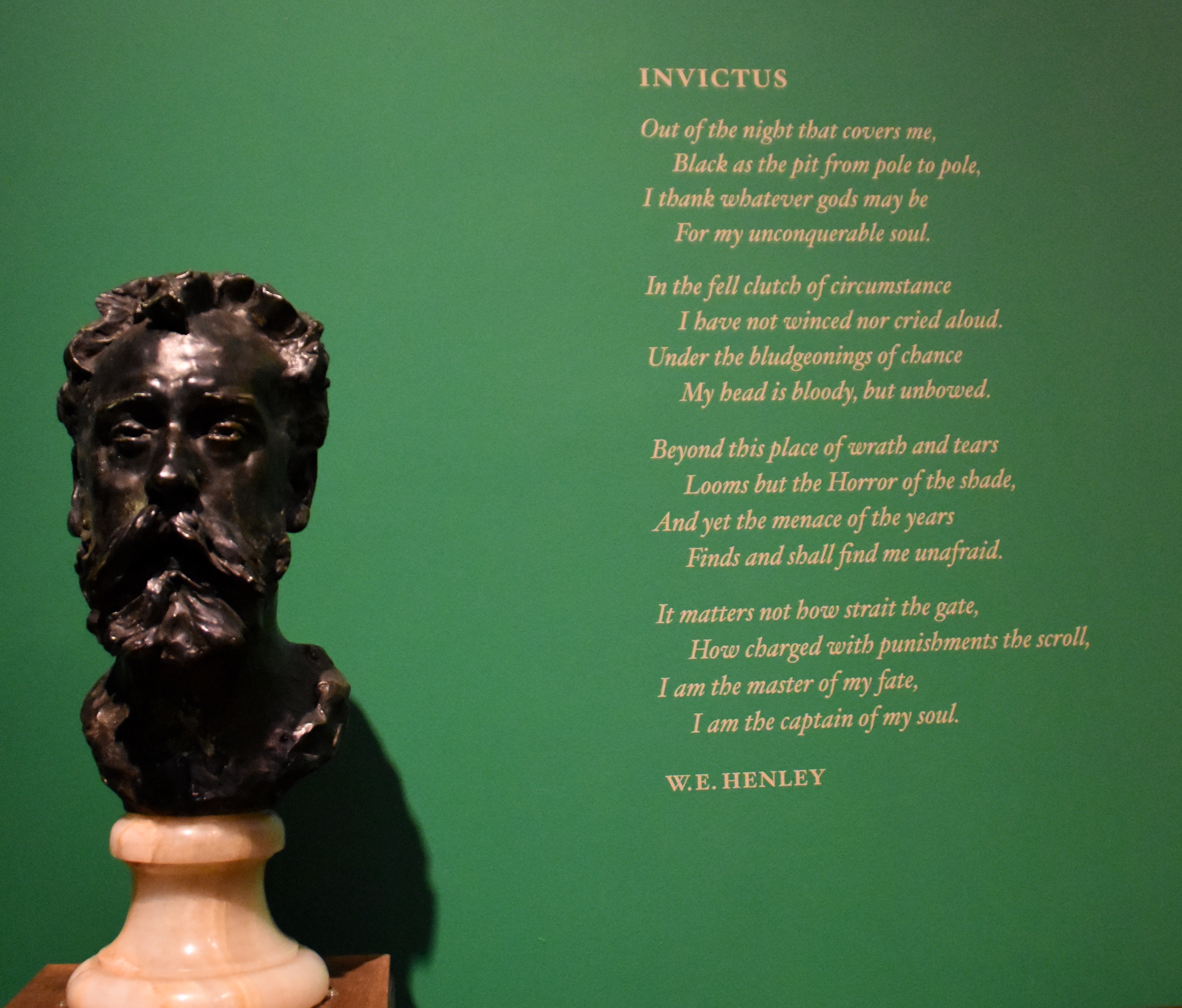

Here is a bust of William Ernest Henley who wrote one of the most influential poems of modern times, Invictus. I’m not sure why there is a bust of Henley in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery as he was English. However, his wife was Scottish and their sickly little daughter Margaret was the inspiration for Wendy in J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. They were friends of Barrie’s and Margaret died before ever reading about the character based on her short life.

Henley wrote Invictus while hospitalized with tuberculosis and had no way of knowing if he would survive it or not. I was absolutely gobsmacked me when I first read it at about age 12 or 13. The closing two lines allowed me to finally drop, once and for all, any pretence that I believed in some ethereal being out there somewhere that was controlling my fate and one that I had to appease with prayer and blind faith. It’s worth listening to over and over again.

After exiting the portrait gallery it’s worth dropping into the library where you’ll find more busts and this very different portrayal of Harry Potter creator J.K.Rowling.

Also not to be missed is the modern portrait gallery you’ll find many new and innovative methods of portraiture as well as photographs, like this one of Annie Lennox.

Time to head to the restaurant and gift shop for some lunch and some post cards of the best works. I hope you’ve enjoyed this tour of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and will give a visit next time you’re in Edinburgh.