The Ancient Orient Museum of Istanbul

This is my second post from a visit to the Istanbul Archaeological Museums, one of the great museums of the world. In the first post Alison and I visited the Archaeological Museum and spent most of the time admiring the incredible collection of sarcophagi on display there. In this post we’ll stroll the grounds and visit the Ancient Orient Museum, but first we will make a brief stop at the Tiled Kiosk. Please join us.

The Tiled Kiosk

Directly across from the Archaeological Museum you will find this building, the Tiled Kiosk which was built by Mehmed the Conqueror in 1472. He was the man who at age 21 in 1453 captured the final Byzantine stronghold of Constantinople and ended the 1,800 year run of the Roman Empire. A kiosk has a different meaning in the Islamic world than what we usually call a kiosk in the west. In Turkey a kiosk is essentially a pleasure palace and there are a number on the grounds of the Topkapi complex of which this one would have been at the outer perimeter at the time it was built. Incorporated into the Istanbul Archaeology Museums in 1953, it has a relatively modest display of Turkish and Islamic art, notably tiles and pottery. If you follow the link above you will find a gallery with photos of many of the best examples. Let’s go inside.

This is a much better photo of the Ab-i Hayat aka the Peacock Fountain than I was able to get and is a great introduction to the richness of Islamic design that one will encounter many times in mosques and other buildings all over Turkey.

I think the best reason to visit the Tiled Kiosk is to get your first look at the wonderful ceramics that highlight some of the best of the decorative arts found throughout much of the Muslim world. This great example pre-dates Columbus’ visit to America, yet is as brightly coloured as if it was fired yesterday.

You will find many places in Istanbul and elsewhere in Turkey selling both modern and antique versions of this style of ceramics and if you’re not up to buying a Turkish carpet, they make great souvenirs. Here is a photo of one that we bought on a previous trip.

The Ancient Orient Museum

Much smaller than the Archaeological Museum, the Ancient Orient Museum features some of the oldest and most important artifacts on display anywhere in the world.

These are portions of what was once considered one of the original Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the Gate of Ishtar to the city of Babylon. It was built by Nebuchadnezzar II, the same guy who destroyed Jerusalem and led the Jewish people into the Babylonian captivity and the builder of the Hanging Gardens as well; he left quite a legacy. Portrayed as an absolute villain in the Bible he was revered as a great builder and conqueror by the Babylonians and their successors.

The animals portrayed here are bulls and dragons. Dragons were the symbol of the chief Babylonian god Marduk who we also encounter in the Bible as Baal, the guy whose prophets lost a sacrifice duel to Elijah on Mount Carmel as described in the first book of Kings.

The other animals adorning the Ishtar Gate were lions which are seen in these two tiles now in the Ancient Orient Museum. Lions were the symbol of Ishtar who was the goddess of sexuality and war and the oldest recorded deity in human history.

The story of the Gate of Ishtar and what happened it is perhaps one of the most controversial in modern archaeology. The gates, which are composed of enamelled bricks, were found in many fragments by the German archaeologist Robert Koldeway not far from modern day Baghdad. From 1904 to 1914 his team clandestinely removed the fragments without permission from the Ottomans who controlled the site of Babylon as rulers of Iraq. Most of the pieces were then polished up and re-erected in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin where you can see them today.

We will be visiting ancient Pergamon on the Adventures Abroad tour Alison and I will be joining tomorrow. When we get there I’ll discuss what else the Germans took from the Ottomans and how it ended up in Berlin. The Pergamon Museum is not the only place you can see pieces of the original Gate of Ishtar. There are examples in the Louvre, the Met and many other places including even the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. I presume the ones we are seeing in the Ancient Orient Museum in Istanbul were a bit of a sop to the Ottomans with whom the Germans had a working relationship right up until the end of WWI.

Not surprisingly Iraq wants the Ishtar Gate tiles back, but given the political instability of that country that’s not going to happen anytime soon. Until then you can view this replica built by Saddam Hussein who thought of himself as the new Nebuchadnezzar.

I mentioned that the Gate of Ishtar was one of the original Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. It lost that distinction when Alexander built his great lighthouse in Alexandria. The final indignity was the use of much of the site of ancient Babylon as an army base by American and Polish troops in the Second Gulf War who drove their tanks over thousands of undocumented tiles and other artifacts from this once wondrous city.

I’ve spent a lot of words on the Gate of Ishtar, but I guarantee that when you see these tiles in person at the Ancient Orient Museum you will be very impressed indeed. Even seeing them for a second time today I was overcome with a feeling of awe in knowing that Nebuchadnezzar II had ridden his chariot through this gate and that the people of Israel were taken through in chains.

Now for something completely different.

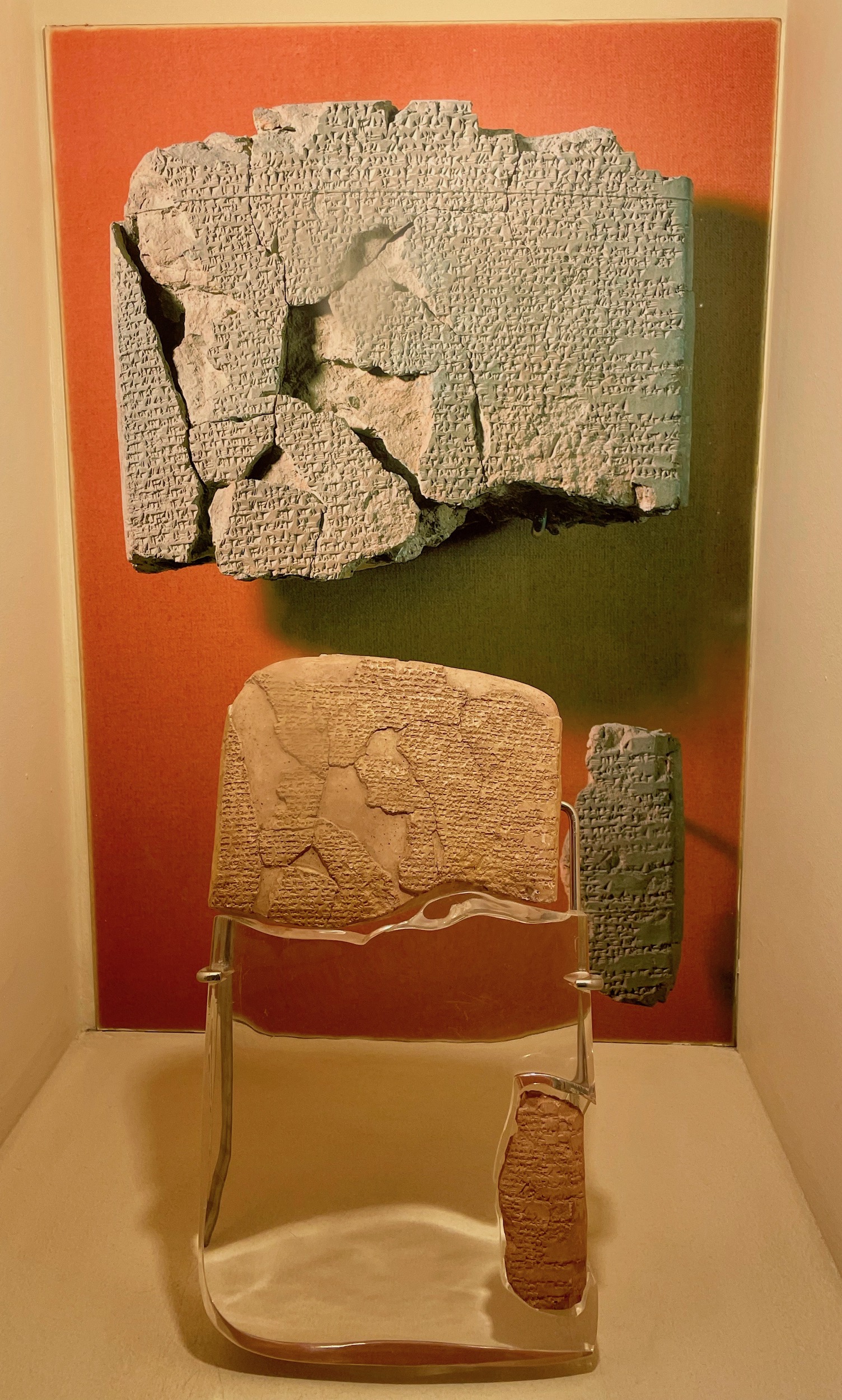

This is the world’s oldest recorded peace accord – the Treaty of Kadesh.

The Treaty of Kadesh was made in 1258 B.C. between the Egyptian pharaoh Ramses II and the Hittite king Hattusilis III ending a long running war between the two great super powers of the time. It followed quite a number of years after the two sides fought what is thought to be the largest chariot battle in history to a draw in the Battle of Kadesh which took place in modern day Syria. In Egypt, a copy of the Egyptian version of the treaty can be seen inscribed on a wall at the Temple of Karnak as well as endless versions of the battle itself throughout Egypt. Ramses II, who was one of the greatest blowhards in ancient history, always had the Egyptians depicted as winning the battle.

However, after the cuneiform tablets now on display at the Ancient Orient Museum were unearthed in the ancient Hittite capitol of Hattusa in 1906 they revealed a different version of events with the Hittites coming out on top. However, whoever won the battle is secondary to the fact that with some variations, both versions of the Treaty of Kadesh are remarkably similar. This a world changing artifact right up there with Hammurabi’s Code, showing that human beings could put their differences aside and try to live in peace. There is a replica of the treaty in the United Nations headquarters in New York. So while these little pieces of inscribed clay won’t blow you away like the tiles from the Ishtar Gate they are of at least equal significance in the story of mankind. BTW there is also a copy of Hammurabi’s Code in the Ancient Orient Museum, but these are not that rare.

Speaking of the Hittites, let’s have a look at some of the more interesting artifacts from that ancient civilization that was based in Anatolia starting with this statue. The subject is unknown – it could be a god , a king or a priest. It dates from the 9th century B.C. well after the earliest Hittite kingdom had disintegrated and a group of smaller Neo-Hittite city states sprang up like Sam’al near the Syrian border where this statue was found. Typical of what we will see in many places on the Adventures Abroad tour of western Turkey, especially at Troy, settlement at places like Sam’al date back to the Early Bronze Age. However, just like an accordion they grow and then contract and grow again etc.etc.etc. What I found most interesting about this artifact was the base with a very kinglike figure holding two lions. As I discussed in the last post, lions were a very real presence in ancient Turkey and figure prominently in Hittite sculpture.

This is one of the more famous finds from Sam’al, a double sphinx that acted as the base for a column. The sphinx of course is a magical creature with the head of a human, body of a lion with the wings of falcon. What is interesting about them is that in Greek mythology the sphinx is a woman and an evil doer. We met a couple on the Lycian sarcophagus in the previous post. In Mid-East and Egyptian mythology the sphinx is a benevolent man. It’s hard to tell what sex these two are, but I’m sure Freud would have had a field day analyzing the reasons why the two cultures came to diametrically opposed views of the sphinx.

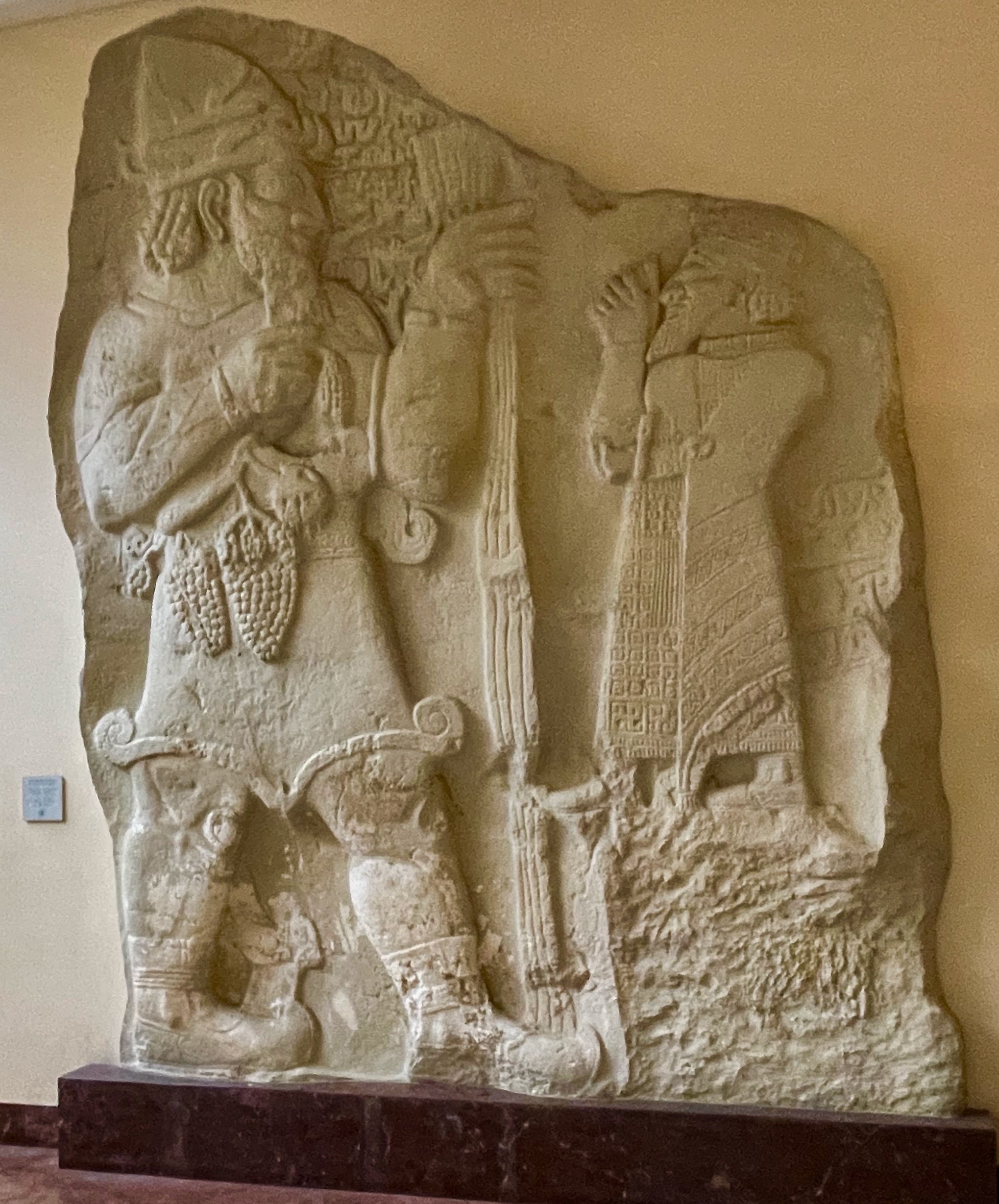

Next we have this copy of what is known as the Ivriz relief. One of the most common forms of Hittite art were reliefs cut into stone as boundary markers or other notifications to passers by. This one depicting King Warpalawas, head of one of the Neo-Hittite city states in south west Anatolia praying to the storm god Tarhunza, is considered the best preserved example. The original can be found in a unique landscape near the village of Irviz that Turkey has submitted to UNESCO for designation as a World Heritage Site. The god holds a sheaf of wheat and has grapes hanging from his belt indicating that food and drink were dependent upon the rains necessary to grow them. The theme of gods controlling the weather is universal. What is not is the portrayal of gods as being of human form. This is a practice that was widespread throughout Mesopotamia, Anatolia and Greece, but not in Egypt, India, the Americas, Africa and just about everywhere else. We take it for granted that gods come in human form because of the Judeo/Christian tradition, but it’s actually the exception rather than the rule in world religions.

When I was a kid just learning about the ancient people of the Mid-East and Egypt I always thought that the toughest dudes on the block were the Assyrians and I can trace that belief to one line in a poem by Lord Byron – The Assyrian came down like a wolf on the fold, And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold;.

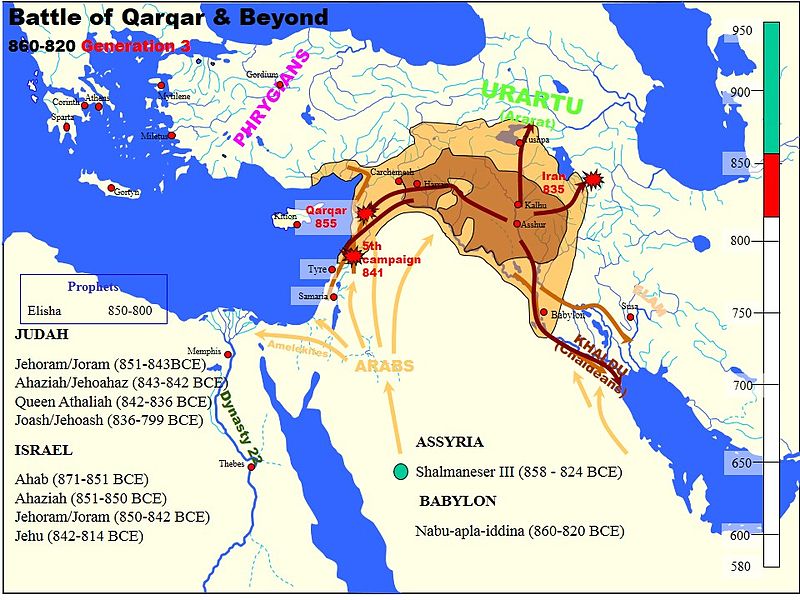

Now this is ironic because the poem is The Destruction of Sennacherib which retells the Biblical story of the Hebrew God destroying the Assyrians attacking Jerusalem in one fell swoop at the hands of an avenging angel. Historically nobody knows why the Assyrians ended their siege of Jerusalem, but I have my doubts that it was because of an angel. While they may not have sacked Jerusalem the Assyrians did destroy Babylon which was a much more prized target as well as dozens of other cities. So they were fearful, had really evil sounding names like Sargon (which I am sure inspired Tolkien’s great fiend Sauron) and had great beards. Let’s look at one of these dreaded Assyrians in the Ancient Orient Museum. This is King Shalamaneser III whose gaze looks like it could turn you stone and unlike King Warpalawas, nobody was going to be bigger than this guy.

He spent his entire adult life causing trouble far and wide as this map of his campaigns shows. However, he kept detailed annals and is important as being the first person to describe Israelites, Arabs and Chaldeans all of whom would go on to play major roles in world history.

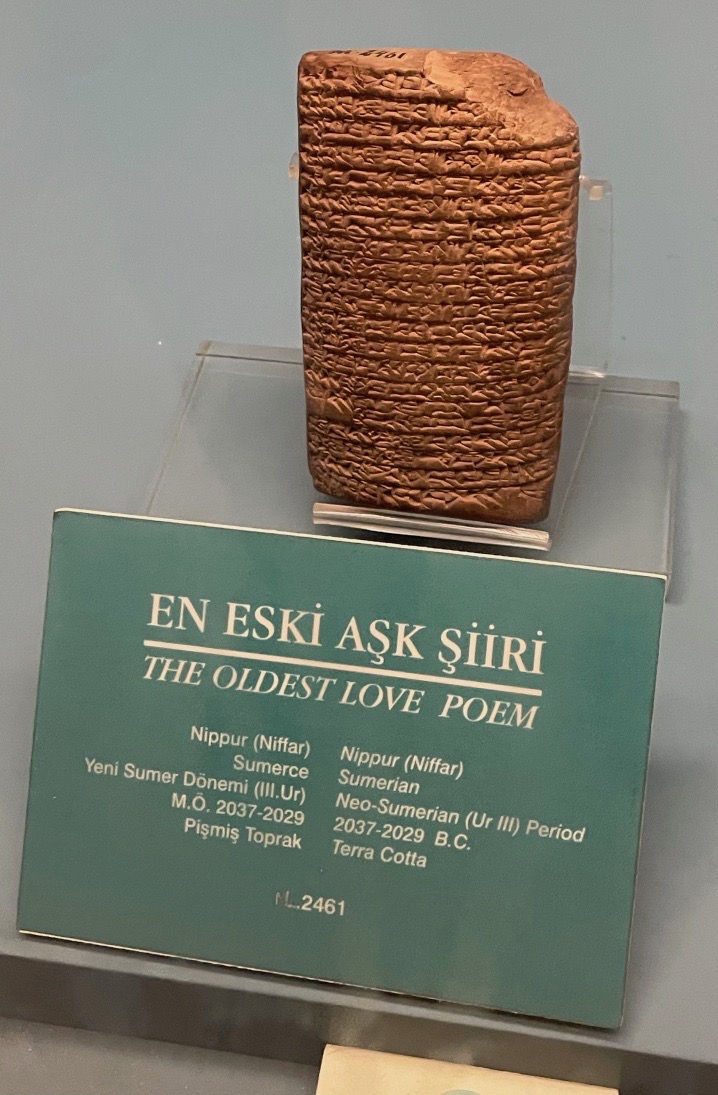

Here is another first, the world’s oldest love poem.

Written in cuneiform over 4,000 years ago it is called the Love Song of Shu-Suen and is an ode from a bride to her bridegroom on their wedding night. Here is the first verse.

Bridegroom, dear to my heart,

Goodly is your beauty, honeysweet,

Lion, dear to my heart,

Goodly is your beauty, honeysweet.

It simply amazes me that something like this could not only survive this long, but that we are able to translate it and discover that human sentiments have not changed throughout history.

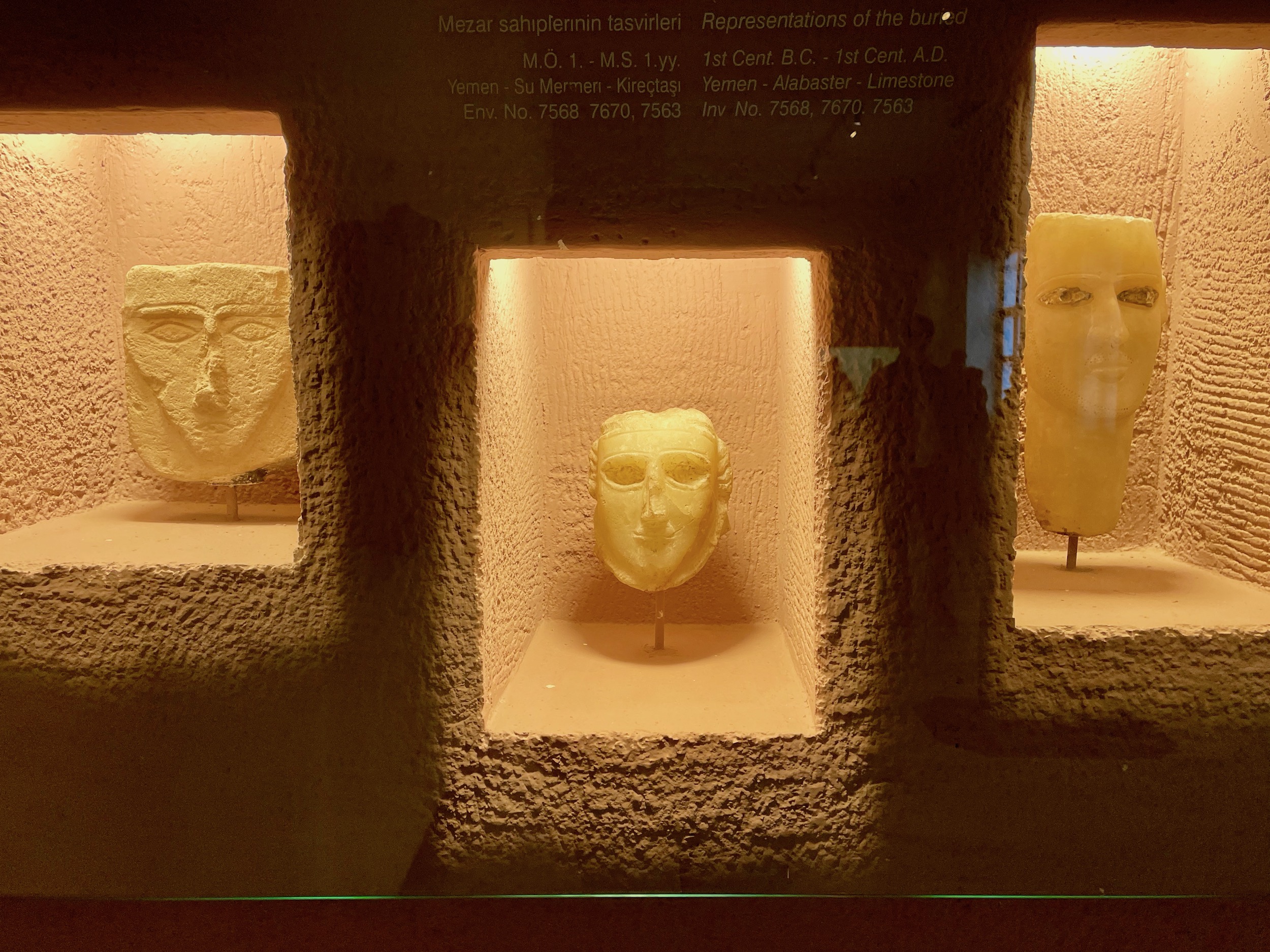

The last items I’ll highlight from the Ancient Orient Museum are these votive statuettes from pre-Islamic Yemen. They are from an ancient cemetery and are meant to represent the persons buried there. Two are in alabaster which makes them almost translucent and I think they have an eerie beauty. When you think of ancient places, Yemen is not one that readily springs to mind and yet its archaeological history goes back to the paleolithic age. Unfortunately, the closest I am likely to get to Yemen given its current civil war is to appreciate these and other artifacts in the Ancient Orient Museum.

And that brings us full circle on the issue of who has the right to claim or possess ancient objects from foreign lands. I think the answer must be that there has to be a balance between keeping in or returning objects to their country of origin and the necessity of protecting them from destruction in places like Yemen or Iraq. For me the answer is not to balkanize the display of ancient art to such a point that the only place you could see Egyptian objects was in Egypt or Babylonian objects in Iraq. If countries want people from other countries to appreciate their history and culture, then they need to be exposed to it in real time and not just from photographs or videos. I’m getting myself worked up here so it’s time to head outside.

These are beautiful Egyptian porphyry sarcophagi called larnax that sit outside the entrance to the Archaeological Museum. They once held the remains of Byzantine Emperors, but we don’t know who. After the conquest of Constantinople all the tombs of the emperors that the Muslims could find were desecrated. Read this article for a more detailed history of these and other porphyry sarcophagi. I’m not sure why these particular ones are left to the elements while others are protected inside, but I can hazard a guess. Still, even on the outs, they have a certain majesty that cannot be taken away.

Our final stop at the Istanbul Archaeological Museum is in the small garden that contains dozens of columns, capitals, plinths and this magnificent head of Medusa.

Medusa is generally portrayed as a terrifying monster, perhaps best captured by Caravaggio in this famous painting.

However, I prefer Ovid’s version of the story from Metamorphoses which tells of a beautiful maiden seduced or even raped by Poseidon in a temple of Athena. When the goddess found out about it she did not take her wrath out on her uncle, but rather Medusa, turning her hair into venomous snakes and a look that turned men to stone. The Medusa that Alison is sitting with has a look of profound sadness at her plight which was entirely out of hands. Make sure you see it before exiting.

Well that concludes our visit to the Istanbul Archaeological Museums and in particular the Ancient Orient Museum, but I have a few more suggestions before returning to the hotel.

The museum is just on the edge of Gülhane Park which was once the private garden of the sultan. It is a beautiful place to wander with many fine specimen trees, flowers, statues, fountains and everything you expect from an urban park. If you follow it to to northern entrance you come out upon Kennedy Caddesi (Street) and suddenly the busy Bosphorus is right in front of you. You can cross the street and follow the shoreline where on one side a lot of people will be fishing and on the other are the outer walls of the Topkapi Palace which is a must visit for another day. About halfway to the next light where you can turn back into the Sultanhamet you’ll find this statue of someone who I know quite well from our time in Malta. This is Turgut Reis aka Dragut, the scourge of Gozo who I wrote about in this post. In 1551 he attacked the island of Gozo and virtually depopulated it by taking almost everyone as a prisoner and selling them into slavery. In 1565 he died in Malta during the great and ultimately unsuccessful siege.

This is the perfect place to end this post as this statue epitomizes the fact that there are at least two sides to every story. Vilified in Malta and much of the Christian world as a ruthless corsair, in the Muslim world he is almost deified as one of the greatest admirals in history.

In the next post we’ll meet our Adventures Abroad guide Yasemin Reis, who just might be distantly related to the guy above and we’ll take a bus tour around the Golden Horn. Please join us as we start the tour in earnest.