Chateau Saint-Louis NHS – History Beneath Your Feet

This is the second of four posts I am writing on lesser known, but extremely important National Historic Sites in the Quebec City area. In the first post I visited Grosse Ile and the Irish Memorial NHS and learned about the 4 million + immigrants who first set foot on Canadian soil there, including my grandfather. In this post I’m visiting the very heart of Quebec City, Dufferin Terrace where over 2 million tourists a year stroll the boardwalk and take in the great views of old Quebec, the St. Lawrence River and the iconic Chateau Frontenac. Although it’s always a pleasure to visit Dufferin Terrace, today I’m not here just for that, but to explore what lies beneath it, the remains of Chateau Saint-Louis the seat of power in New France and colonial Quebec for over 200 years. Please join me on a guided tour of this once long forgotten place.

I’m staying in Levis across the river from Quebec City which allows me to take the ferry to get right into the old part of the city without any hassle and provides this great view that you can only get from the river.

I’m met at the ferry terminal by my Parks Canada host Philippe Gauthier and together we make the walk up to Dufferin Terrace passing a number of familiar landmarks along the way including the sign for the Vendome Restaurant which features a smooching couple in a horse drawn carriage. An institution in Quebec City since the 1950s, the Vendome closed a few years ago and all that’s left is the iconic sign.

Arriving at Dufferin Terrace, a bit out of breath, we meet Simon Careau, the Parks Canada expert on Chateau Saint-Louis and Napoleon as well. He gives me the history of Chateau Saint-Louis which I have to admit I was completely unaware of before meeting with Eric Magnan at the TMAC conference in Saskatoon in June. He filled me in on the importance of the place in Canadian history and I knew I had to visit the next time I was in Quebec which happened to be just a month later. So between Eric and Simon this is what I learned.

History of Chateau Saint-Louis

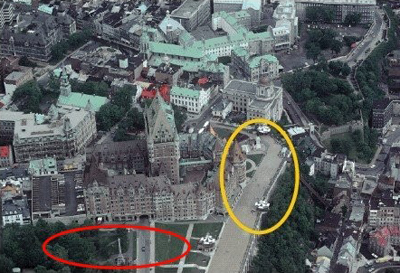

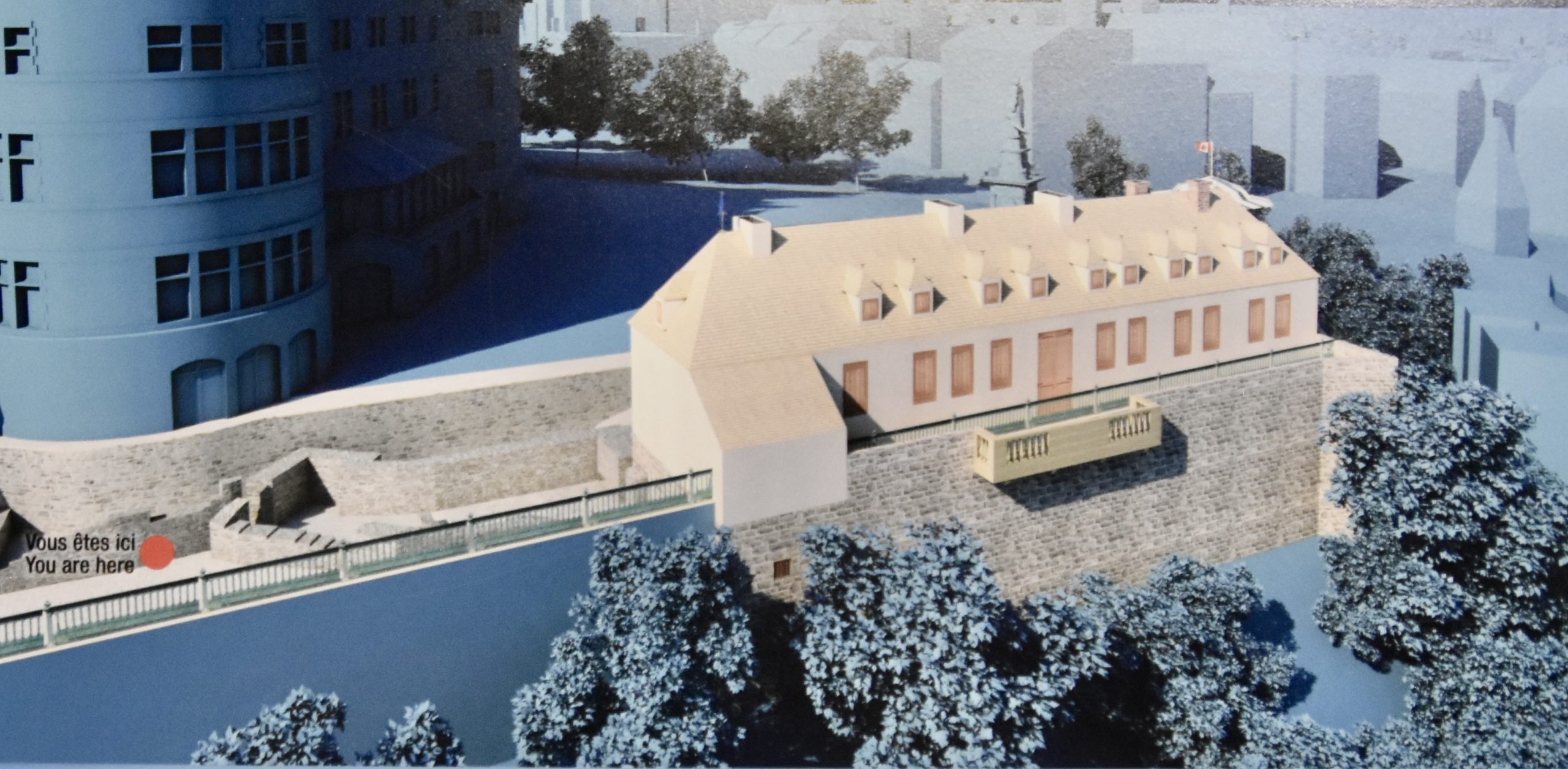

Technically the proper name of this National Historic Site is Saint-Louis Forts and Chateaux and it takes in an area much larger than what I am about to visit today, which is basically the remnants of Chateau Saint-Louis, the Governor’s Palace up until it burned down in 1834. There were also four forts and extensive gardens, all of which are now long gone and buried underneath Dufferin Terrace and even parts of Chateau Frontenac. This aerial photo from the Parks Canada website shows the location of the forts and gardens as well as the Chateau Saint-Louis. The forts and chateau are under the yellow oval and the gardens under the red one.

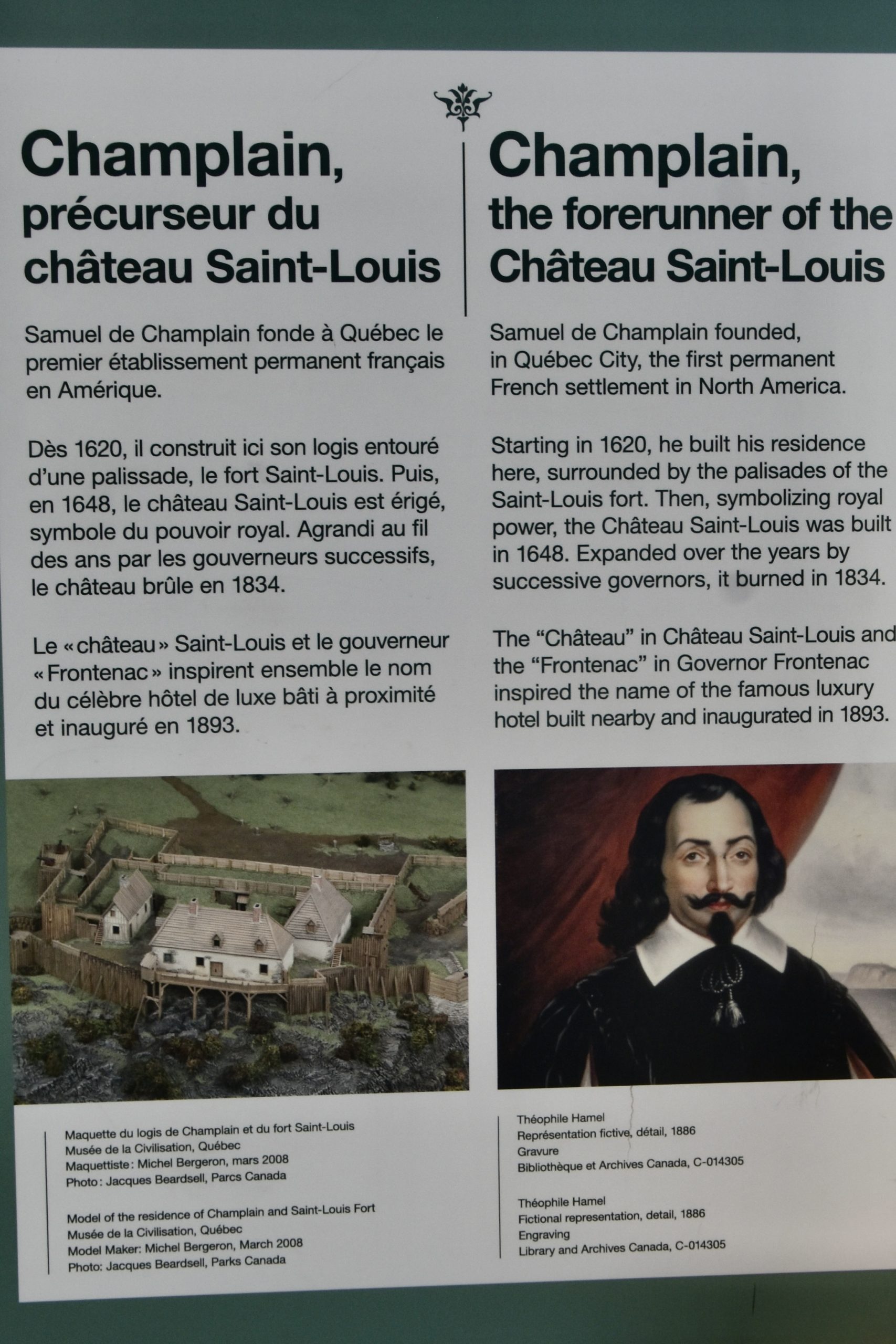

Most Canadians will or should know that Samuel de Champlain founded Quebec City in 1608, a few years after creating the French presence in North America at the Habitation at Port Royal in Nova Scotia. Initially he built a wooden palisade not that much different than that he built at Port Royal, but in 1620 he ordered the construction of the first of the four forts that are part of the National Historic Site. This was replaced by a second fort in 1626, also under the direction of Champlain. After Champlain died in 1635, he was succeeded by Charles Huault de Montmagny who built the third fort in 1636 and the first chateau in 1648 as well as the first garden. For the next almost fifty years things remained as they had in the Montmagny era, until another famous figure in the history of New France arrived on the scene. Louis de Buade, aka The Comte de Frontenac served two terms as governor of the colony, the second of which saw him build the fourth and final fort on the site and more importantly for our purposes, the second chateau which is what we now call Chateau Saint-Louis, named for Louis XIV.

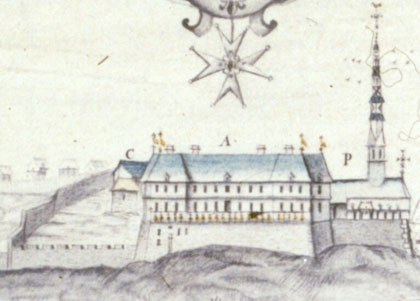

This is what it looked like in 1700 – a pretty imposing structure by any measure.

It was expanded again in 1719 and remained that way until Quebec City fell to the British in 1759 and New France was formally ceded to the British in 1763. From that time until its destruction in 1834 it was the residence of the Governor Generals of Quebec. Under three of them, Murray, Haldimand and Craig the Chateau Saint-Louis became a palatial residence, fit for a king’s or queen’s representative.

This is what it looked like in 1800.

A third story was added by Governor General Sir Henry Craig in 1808 which marked the final version of the Chateau Saint-Louis that burned to the ground in 1834 and was not only not rebuilt, but seemingly completely forgotten about for the next 130 years. The first terrace was built over the remains of the structure in 1838 named for Governor General John Lambton, Earl of Durham who wrote the famous report that led to the union of Upper and Lower Canada in 1841. In 1879 it was renamed Dufferin Terrace after Governor-General Lord Dufferin who many consider to be the model after which most subsequent Governor-Generals made their approach to relations between Britain and Canada.

In 2005 an extensive archaeological program that lasted until 2007 was undertaken by Parks Canada which revealed the extent of Chateau Saint-Louis and uncovered a veritable treasure trove of artifacts – well over a million. In 2008, on the 400th anniversary of the founding of Quebec City Chateau Saint-Louis was opened to the public and was incorporated into the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Old Quebec.

Today visitors can take a guided tour or tour on their own with an audio guide. Either way it is a site that should be part of every first time visit to Quebec City, but you must arrive between the middle of May to the middle of October as it is closed for the rest of the year.

OK, let’s join Simon and Philippe and start our tour of Chateau Saint-Louis.

You enter the NHS through the Frontenac Kiosk on the western end of Dufferin Terrace and descend down a set of stairs to enter what was essentially the basement and out buildings of Chateau Saint-Louis.

However, before entering, take a moment to read this sign board outside the kiosk to learn how the Chateau Frontenac came by its iconic name.

Touring Chateau Saint-Louis

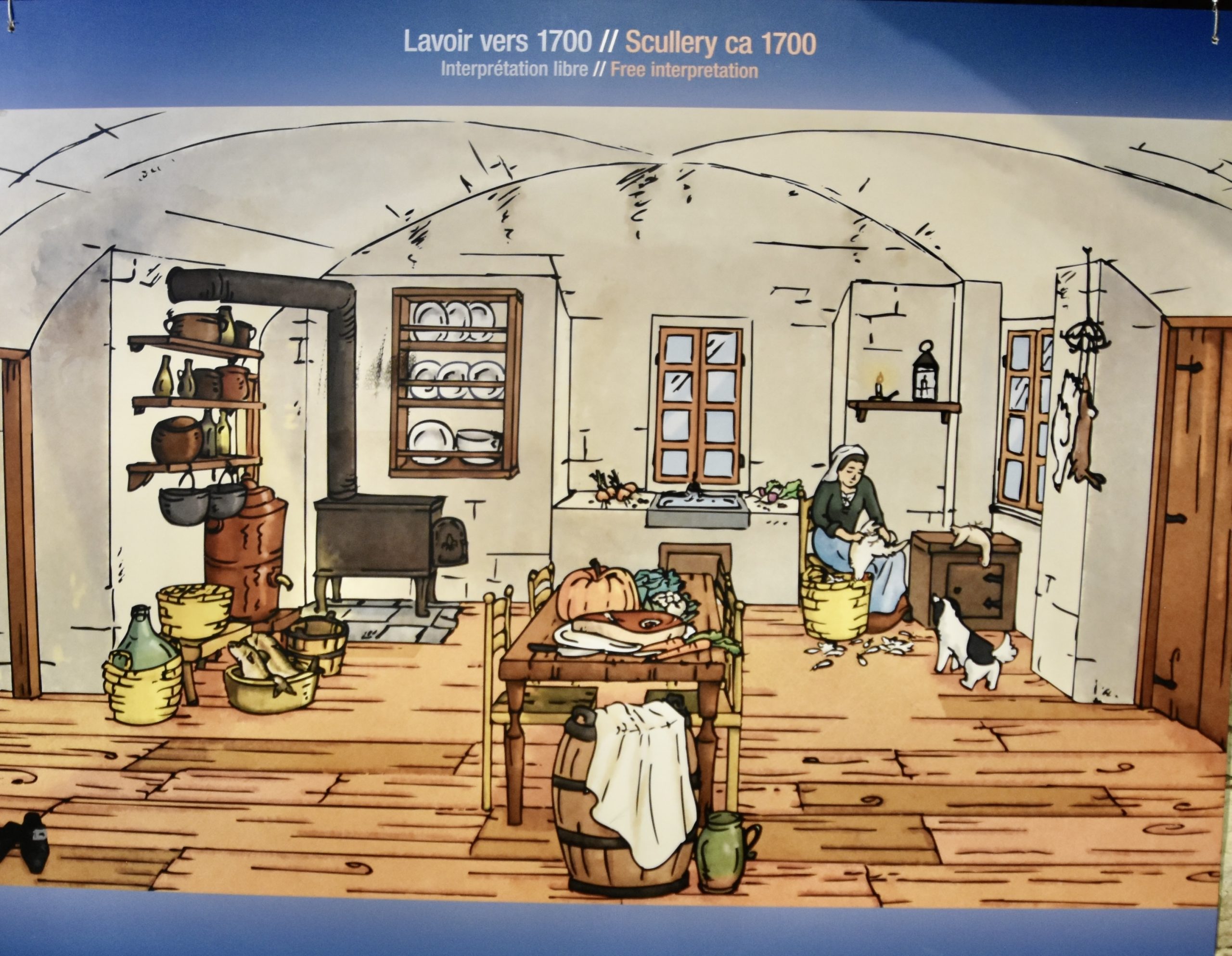

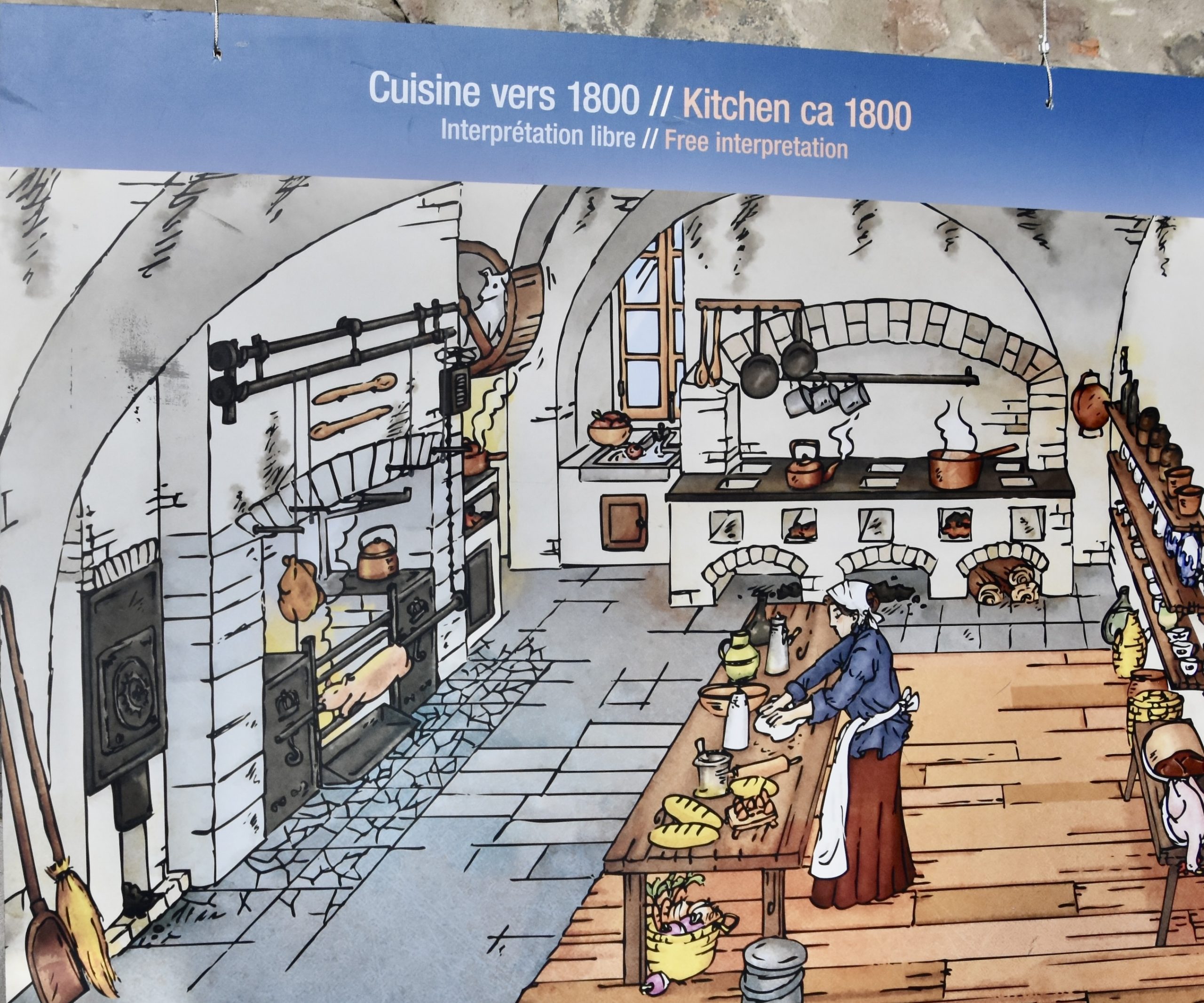

Keeping in mind that what remains of Chateau Saint-Louis is essentially only the basement, Parks Canada commissioned the late Suzanne Duquet, a prominent Quebecois artist whose works are found in the National Gallery, to create a series of paintings to depict what the various rooms in the chateau would have looked like way back when. They are very useful in getting the picture as it were, starting with this one of the ice house which is the first place on the tour.

In the winter ice would be harvested and could be stored underground throughout the summer and fall, giving the equivalent of a modern refrigeration system. Note the white carcasses of the snow geese that for millennia have been migrating through this area of the St. Lawrence.

Here is the actual ice house.

Still not under the Chateau Saint-Louis proper, there is a series of photos of models that depict the evolution of the building from the time of Champlain up until the final version created by Governor General Craig.

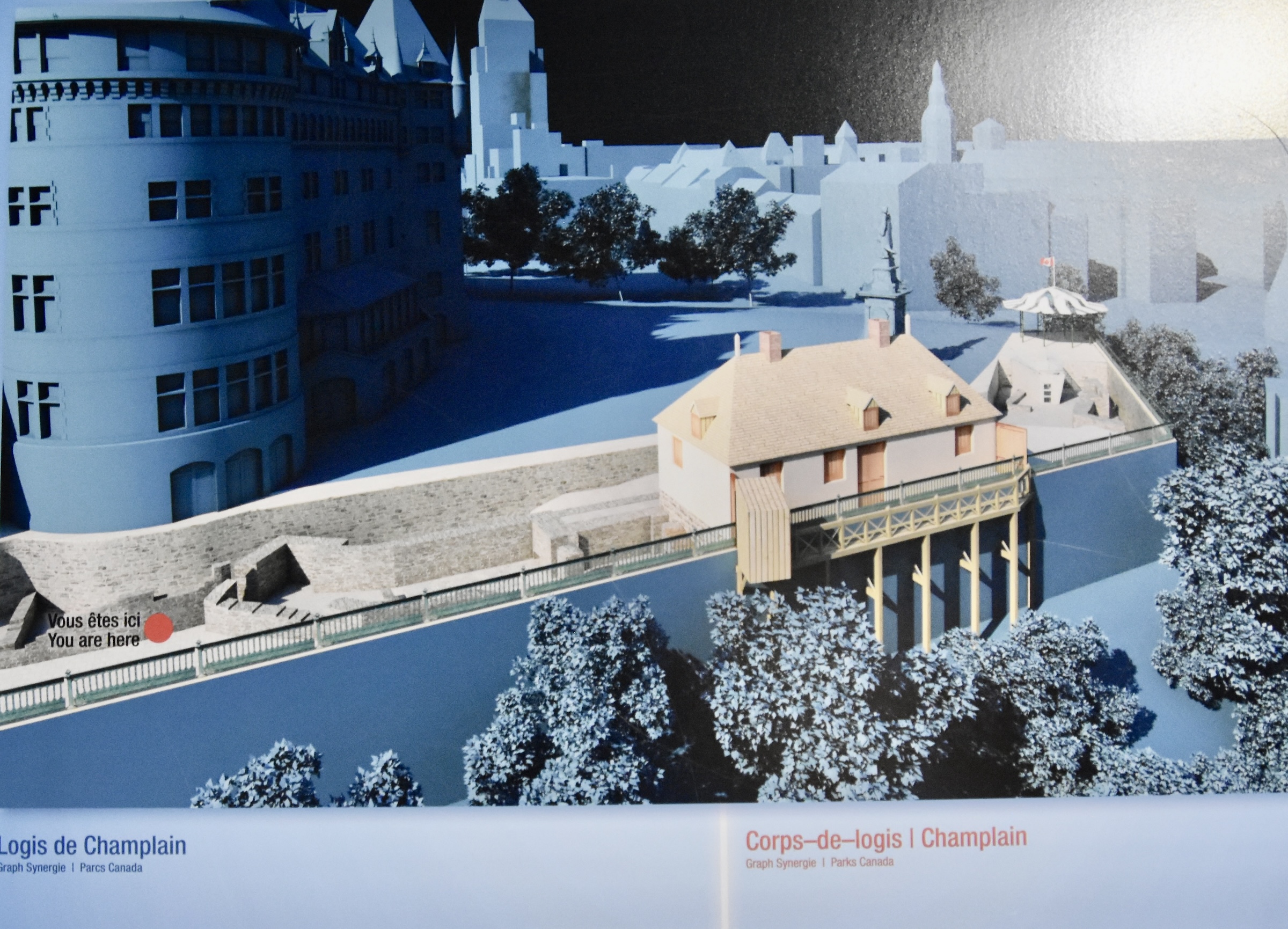

This is the original Champlain chateau. Two things are of note – the first being that the location you are now in is nowhere near the original building, giving an idea of just how much it was expanded over the centuries. The second is looming presence of the Chateau Frontenac which has been added to give a perspective of the exactly where the Chateau Saint-Louis was in relation to the more modern buildings.

Next we see the Montmagny structure from 1646 which now does resemble a true chateau.

Next we see the version that Frontenac had constructed, pretty well tripling the Montmagny building and really looking grand sitting as it does on the very edge of the cliff overlooking Lower Quebec.

Lastly are the two versions under British rule, the 1769 structure, not that much different than that of Frontenac, but the final building sporting a new third story and now truly a monumental structure. It seems almost unbelievable that something like this could be completely destroyed and forgotten about for well over a century.

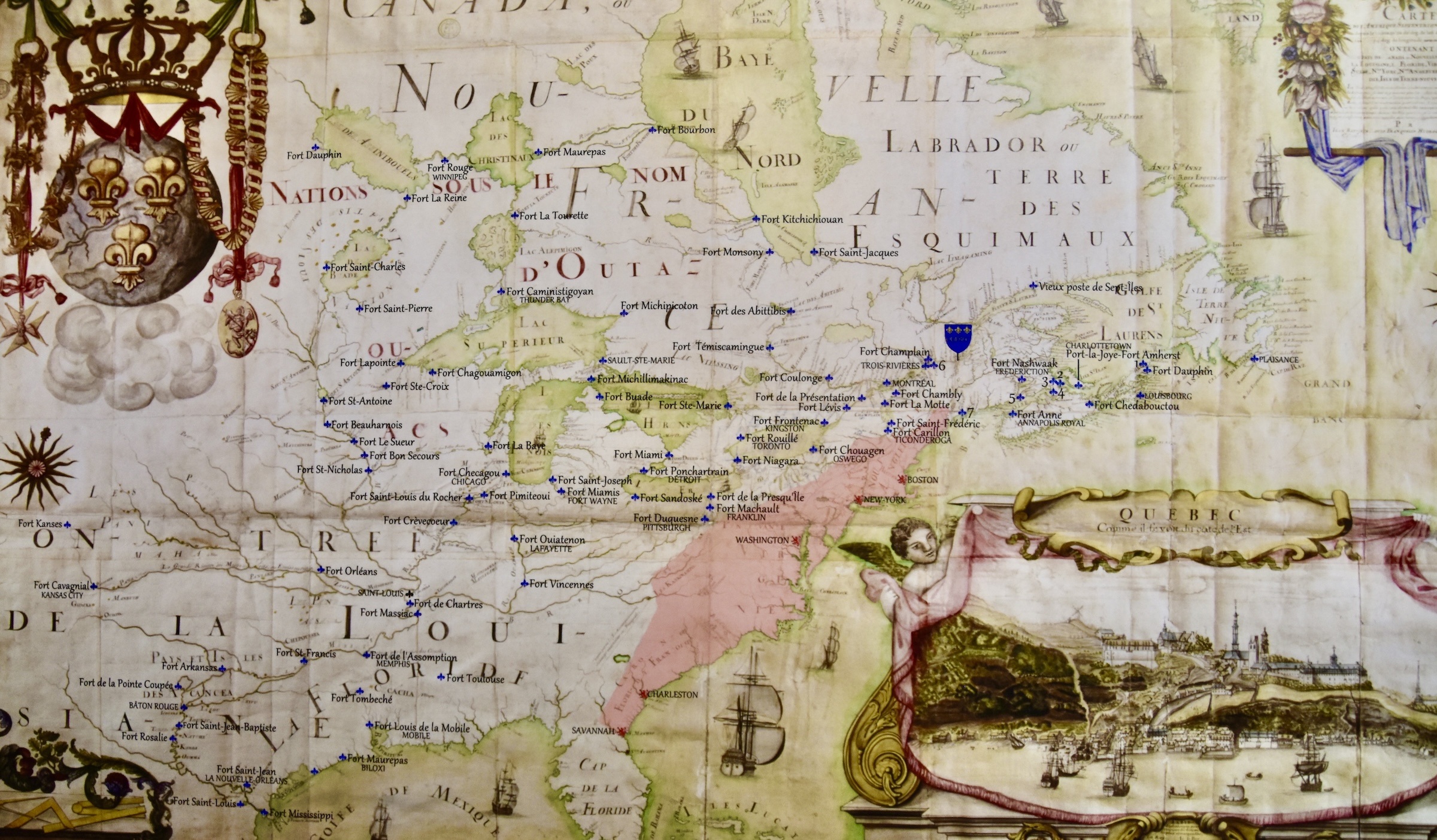

Entering under the actual basement you see this giant map of eastern North America roughly at the outbreak of the Seven Years War in 1756. The blue shield is Quebec City and it was from here in this building that the massive territory stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Canadian prairies and all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico was governed. The British presence outlined in pink along the Eastern Seaboard is but a fraction of the French and brings up the question, how did they win? Simple, they had far more people. The French were interested in commerce, the British more so in colonization. It is estimated that New France had between 60,000 to 80,000 inhabitants at the outbreak of war, while the British colonies had over a million.

What really struck me about this map was just how many French forts there were by the 1750’s.

I should note that there are hundreds of artifacts on display in many cases in the different rooms. Here is a photo of Simon Careau behind one of these display cases.

However, with a few exceptions, I’m going to concentrate more on the rooms themselves rather than their contents. The first room you come to in the basement of the Chateau Saint-Louis is the scullery which is depicted here as it would have looked in about 1700.

Scullery is not a word you hear much these days and refers to that part of the kitchen where the dirty work was done like washing the dishes or as depicted here, plucking one of those snow geese from the ice house.

Next we fast forward a hundred years to the kitchen in 1800.

There is an amazing detail in this painting that I would never have noticed had Simon not pointed it out. See the pig and the turning spit. Then look up to the top and see the little dog. Just like a hamster, he is turning the spit by running inside a wheel. I had no idea that dogs were ever used in this way. Named turnspit dogs, they were bred for their short legs and stamina. The expression ‘Work like a dog’, is thought to refer the work these little guys did.

This is that same spit oven as it looks today. You can see why the Suzanne Duquet paintings make it easier to visualize what it might have looked like when in use.

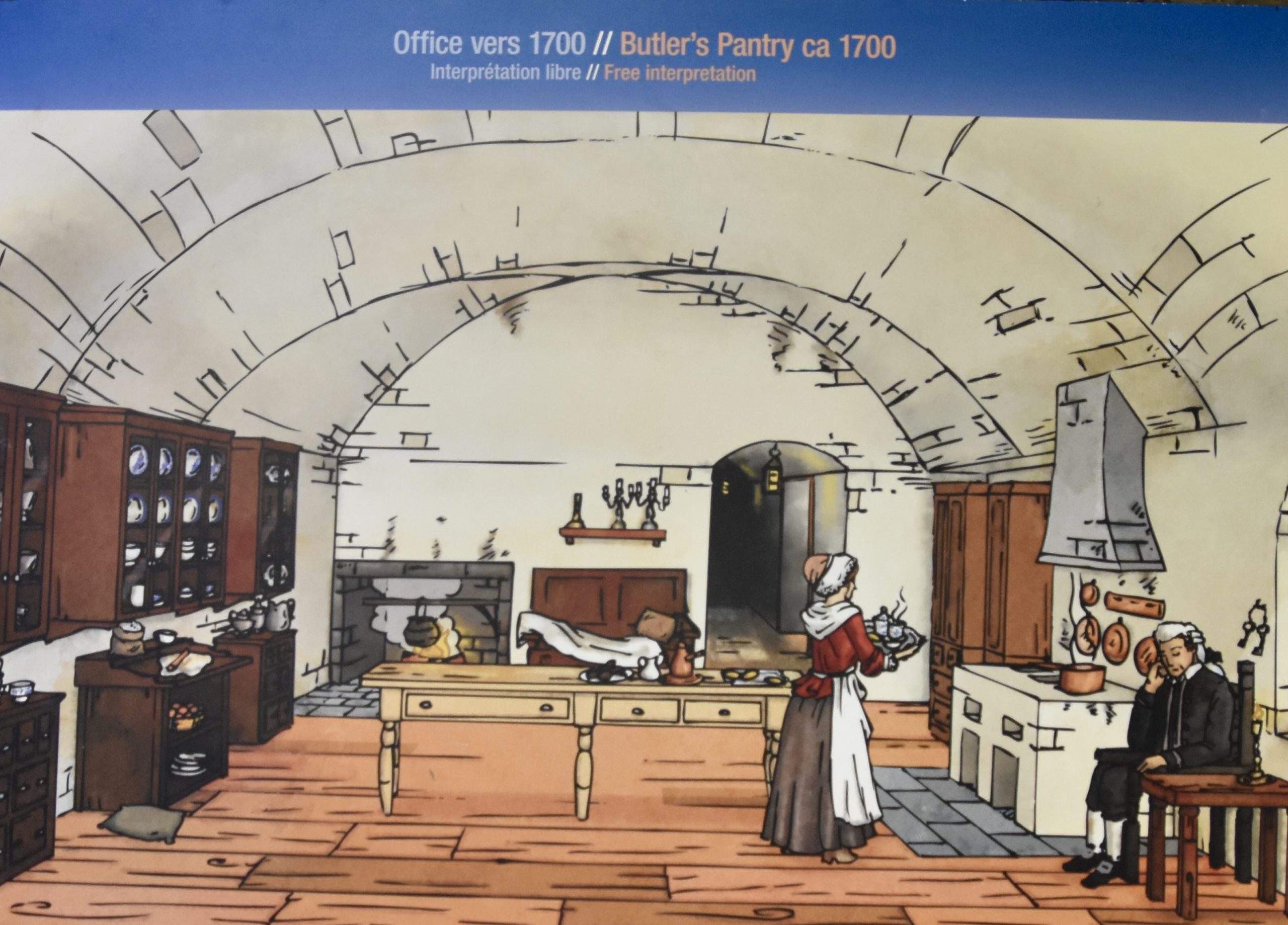

The next room depicted in the paintings is the Butler’s Pantry. Stepping back a century we see the seated butler who was the equivalent of Charles Carson in Downtown Abbey. He ran the show below ground and was responsible for overseeing all that went on in the cellars.

These are just a few of the artefacts that were uncovered in this area of Chateau Saint-Louis.

By this point you will have reached the site of the original Champlain building dating back to 1626 and here there is a display case of items dated to the Champlain period which would be almost four centuries ago.

Note what appeared to me to be a precious ring, but Simon advised that these were common items of trade with the Indigenous peoples and not of any great value at the time, but extremely rare today.

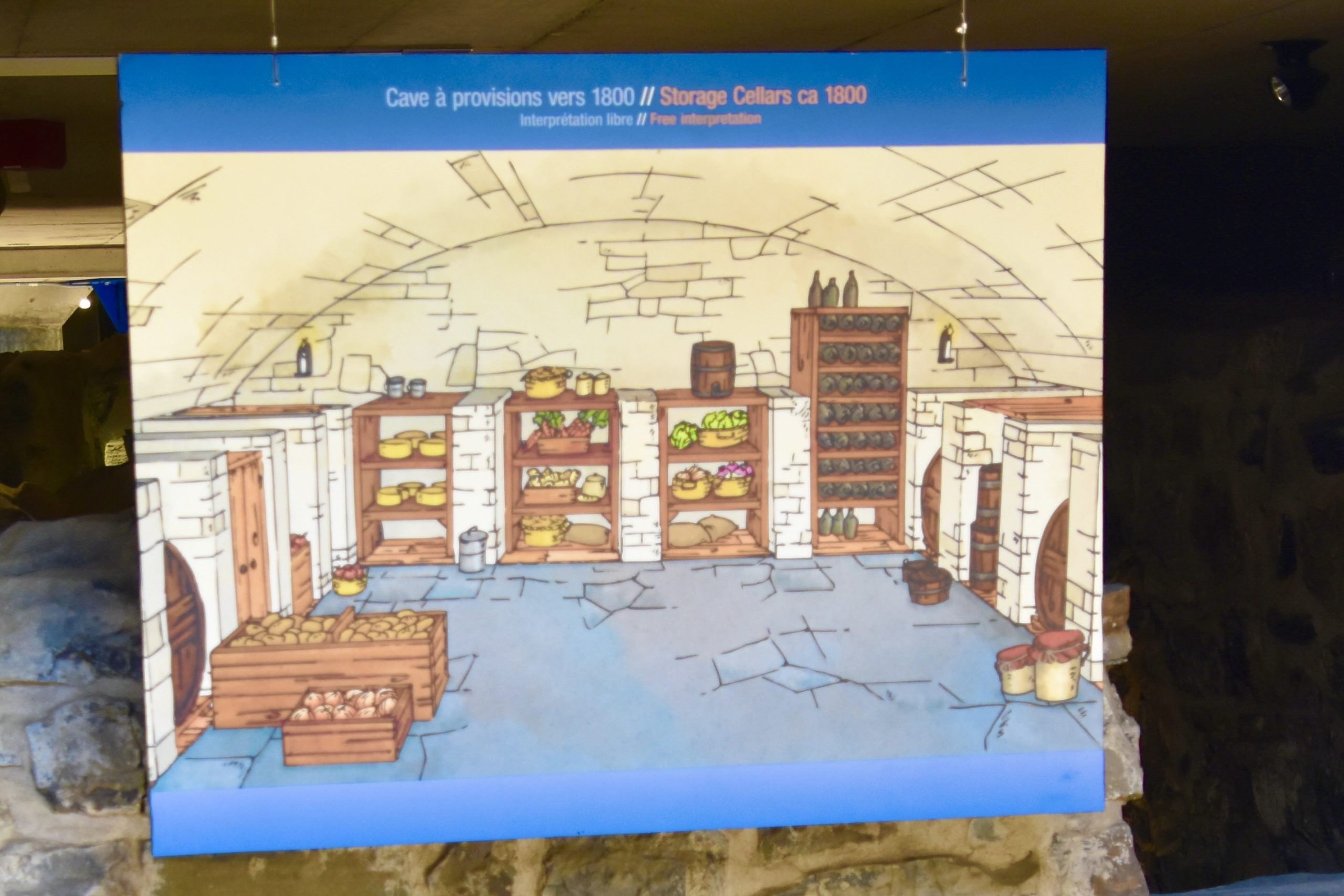

The last painting in Chateau Saint-Louis depicts a simple storage cellar.

Parks Canada has created three archeoscopes that allow visitors on Dufferin Terrace to look down on the interior of Chateau Saint-Louis. I have been in many places around the world where you can walk over glassed in archaeological ruins, but I’ve never been in one where you could be looking up from the ruins. This is the view of Chateau Frontenac from one of these archeoscopes.

I said goodbye to Simon and Philippe after our visit and was about to make my way to the next Quebec City National Historic Site, Fort Levis No. 1, but had one more stop before going back to the ferry.

Montmorency Park National Historic Site

Not far from the hustle and bustle of Dufferin Terrace is this tranquil little park that has played an outsized role in Canadian history. It is Montmorency Park National Historic Site and was once the site the Quebec Parliament buildings. I say buildings, because there were not one, but two Parliament buildings once situated here and like the Chateau Saint-Louis, they too both succumbed to fire. But not before the conference that laid out the constitutional structure of the future country of Canada was held here in 1864. The Quebec Conference followed on the earlier Charlottetown Conference where the idea of a unification of four British colonies into one country called Canada was agreed upon. At this very spot where I stood to take this photo, the bones of that agreement were put into place.

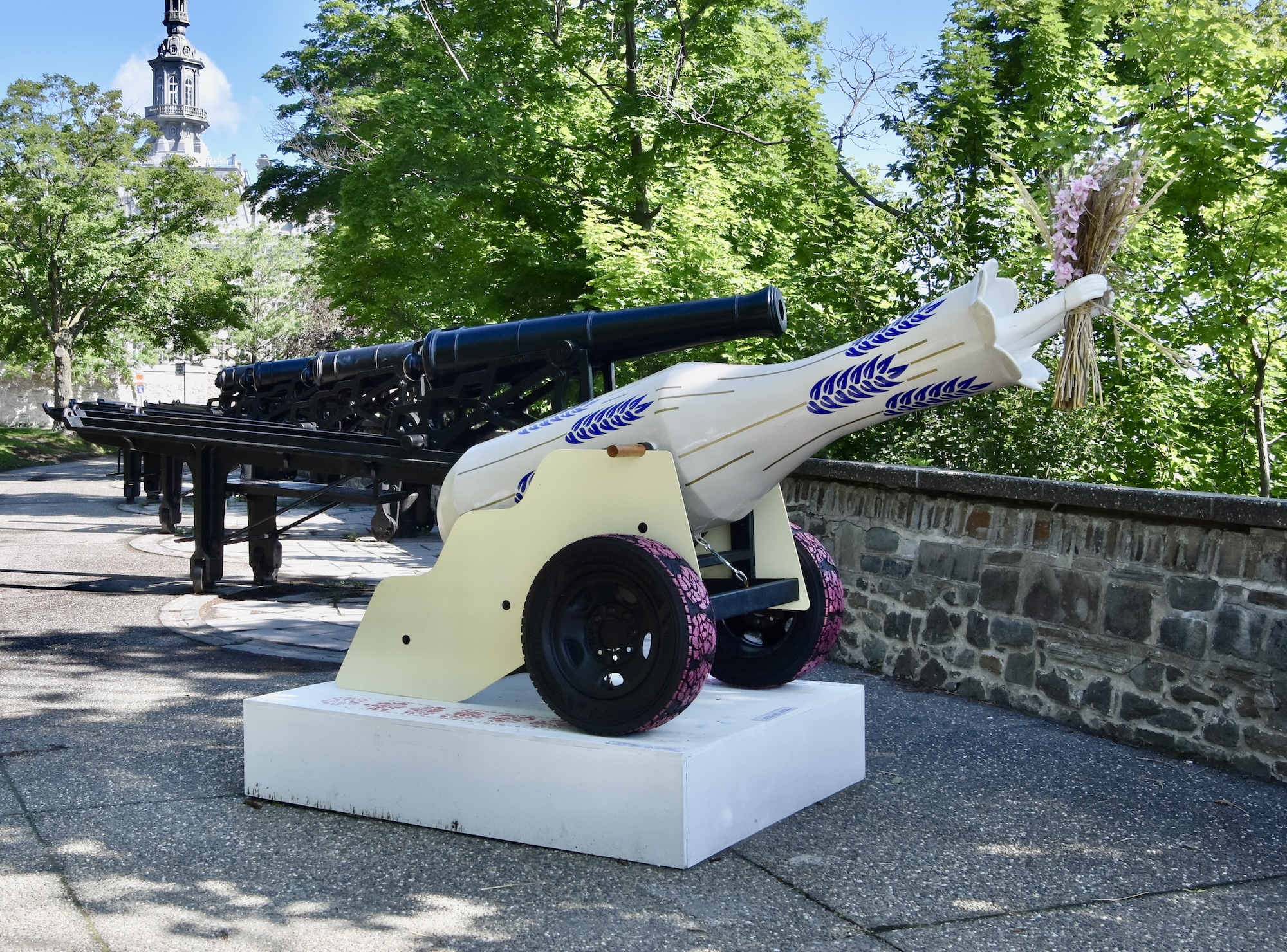

Now it’s an almost forgotten memory and most people come for a view of the cannons that once guarded the place Along with one modern addition.

Also on the grounds is a statue of Sir George Etienne Cartier, the Quebec politician who along with Sir John A. MacDonald is considered the major figure in creating the union between French and English that has endured for over 160 years.

I hope you have enjoyed the tour of Chateau Saint-Louis and that I have inspired you to visit it in person. As noted, next we will head across the river to Fort Levis No. 1. See you there.