Forges du Saint-Maurice NHS

This is my fourth and final post from a recent trip to Quebec to visit lesser known, but important National Historic Sites administered by Parks Canada. The three previous posts featured Grosse Ile, Chateau Saint-Louis and Fort Levis No. 1. In this post I’ll move away from the Quebec City area to Trois-Rivières some 130 kms. (81 miles) upriver where, on the outskirts of the second oldest settlement in New France, I’ll visit the Forges du Saint-Maurice National Historic Site where the Canadian iron and steel industry was born. As with the previous three visits this proved to be a real learning experience which I’ll share with my readers in this post.

History of the Forges du Saint-Maurice

Trois-Rivières was founded by Samuel de Champlain in 1634 at the confluence of the Saint-Maurice and Saint Lawrence rivers. Originally basically a fur trading post, the settlement saw little growth for the first century of its existence, although from very early on it was known that the area was rich in iron deposits and limestone, two of the three components in the 17th century iron working industry. The third component was wood charcoal and the forests of New France could produce that in abundance. However, France did not encourage industrialization in its colonies and no effort was made to exploit these resources until 1730 when Intendant Gilles Hocquart granted Francois Poulin de Francheville, the seigneur of Saint-Maurice, the exclusive right to mine the iron ore of the region. He chose a site just north of Trois-Rivières where a stream enters the Saint-Maurice River to build a forge powered by two water wheels on the stream. Unfortunately Francheville died unexpectedly and the first forge was not a financial success, although it did produce enough high quality iron to attract the attention of the French authorities in Paris.

In 1735 French ironmaster Pierre-François Olivier de Vézin was sent to assess the viability of the site and he recommended building a blast furnace to complement the forge. For definition’s sake, a forge is where iron is heated and pounded into specific finished products while a blast furnace is where iron ore is smelted into pig iron, the basic building block of steel and cast iron. King Louis XV granted him Francheville’s rights and with two partners they began building a European style iron and steel making complex on what would become the Forges du Saint-Maurice.

Things did not go smoothly at first, but eventually a blast furnace and two forges were producing up to 400 tons of cast iron which in turn produced 200 tons of wrought iron, which is much more malleable than cast iron. Experienced ironworkers were imported from France along with their families and the Forges du Saint-Maurice became the first ‘company town’ in Canada. As you tour the grounds of the National Historic Site you can see the remnants of the houses that were dismantled after the forges closed in 1883.

The most imposing structure at the Forges du Saint-Maurice is the Grande Maison, the ironmaster’s house, which was rebuilt by Parks Canada exactly as the original building that now serves as the exhibition centre for the site.

Once firmly established, the Forges du Saint-Maurice produced an amazing variety of goods from cannonballs to kitchen stoves. Originally producing most things for the military, it did follow the urgings of the Prophet Isaiah, and figuratively transitioned from swords to plowshares.

For well over 150 years the Forges du Saint-Maurice was a major going concern employing hundreds of workers and then it closed and literally disappeared from view as all the buildings were demolished and its place in history largely forgotten. In the 1970s Parks Canada began a major archaeological project at the abandoned site and over the next fifteen years resurrected the blast furnace, the lower forge and the ironmaster’s house. It is now one of the most impressive National Historic Sites in the country, but also one that receives only a fraction of the visitors of the Quebec City and Montreal area sites.

With this very cursory introduction let’s take a tour of the Forges du Saint-Maurice.

I arrived at the site at opening hour and was the first car in the parking lot. The visit starts at the Grande Maison which has exhibits on the main floor and cellar that feature the most important figures in Forges du Saint-Maurice history as well as many of the products that were made here. The cellar also features some of the most interesting local legends associated with the long history of the Forges du Saint-Maurice. On the upper floor there is a 20 minute multi-media presentation A Story Cast in Iron which gives a great overview of the National Historic Site. From the Grande Maison you make your way to the blast furnace, passing by some of the outlines of the former village residences. The blast furnace has a 15 minute video, 1600°C Trial by Fire, that takes you through the steps required to smelt the iron ore and turn it into cast iron. Lastly, you can walk past the upper forge down to the lower forge and get a look at the Saint-Maurice River which is pretty impressive.

So let’s get started.

On entering the Grande Maison you see this mural depicting the blast furnace as a figurative hell on earth.

And the first of a series of cast iron sculptures depicting various figures associated with the iron making process.

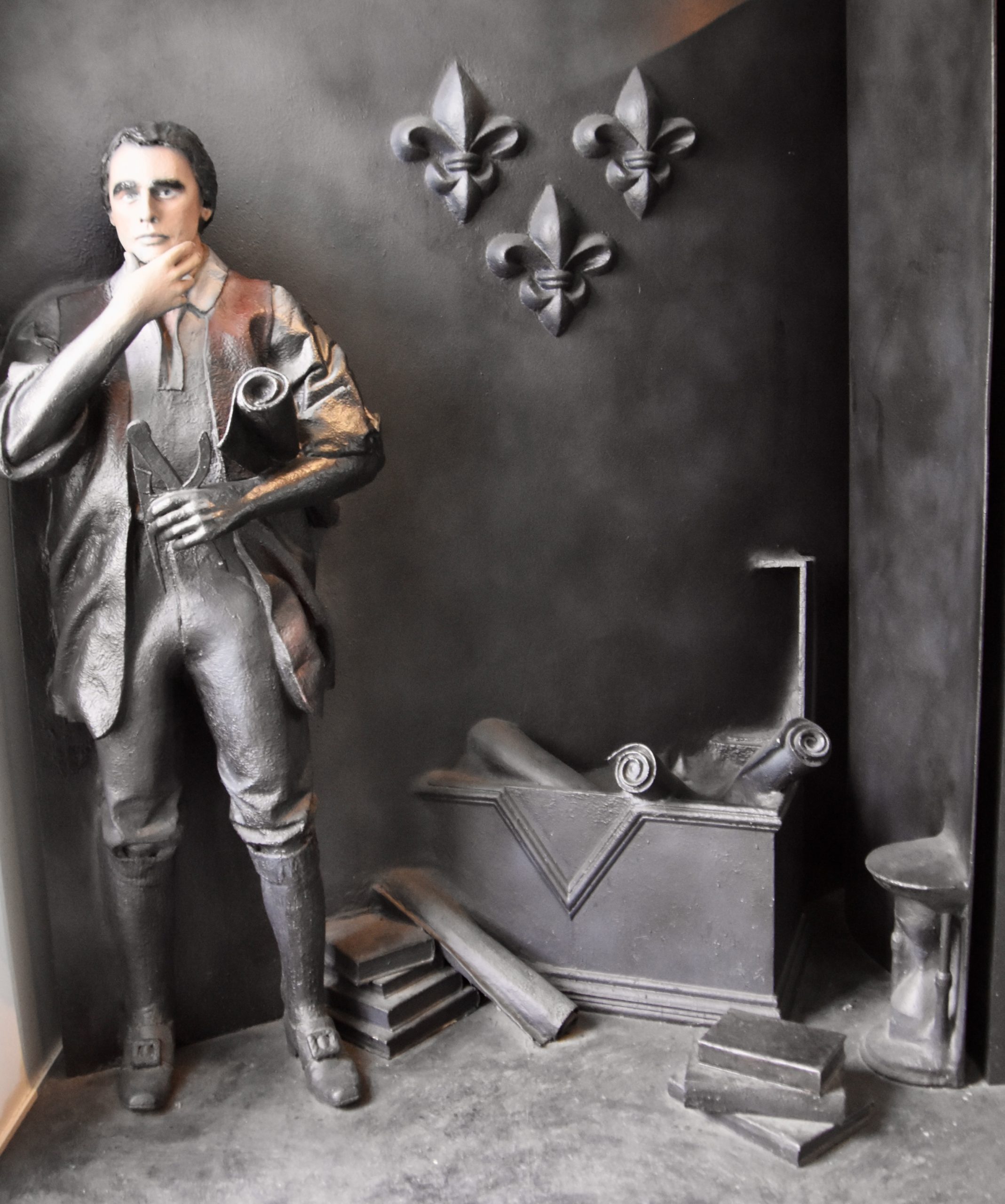

After watching the multi-media presentation you follow a dedicated pathway through the first floor and cellar that tells the story of the Forges du Saint-Maurice in chronological order starting with the sculpture of Pierre-Francois Olivier de Vezin shown above.

This is Matthew Bell, the British ironmaster who oversaw the Forges du Saint-Maurice at its height of production when it employed as many as 450 workers.

This sculpture encompasses the tools of the forge’s tradesmen.

This is John MacDougall who oversaw the transition of the Forges du Saint-Maurice to a more modern industrial facility producing mass quantities of pig iron for railway car wheels and other components of the 19th century Industrial Revolution.

Entering the cellar you come upon a huge storeroom.

And take a tour past the many products made at the Forges du Saint-Maurice during its 150 year history starting with cannonballs and bombs for the French military.

Then transitioning to exquisite cast iron stoves that bear the distinctive F.St.M. logo that makes them very rare collector’s items today. For some reason this exhibit and the next one are cast (pun intended) in this greenish aura.

The next phase saw the Forges du Saint-Maurice producing a wide variety of both household items like cast iron pots and pans to plowshares.

The final phase was the mass production of pig iron to be made into massive railway car wheels. The Forges du Saint-Maurice had come all the way from the Colonial era where conflict between French and English was at the forefront to contributing to the modernization of the new country of Canada.

The final exhibits in the Grande Maison at the Forges du Saint-Maurice are three that reflect the deep sense of mystery and a pervasive aura of devilry associated with a place that literally resembled hell on earth. Quebec has rich history of folklore and legends in which the Devil plays an outsized role as these three sculptures depict.

Edward Tasse was a worker at the blast furnace who said he was afraid of no one including the Devil. This sculpture depicts Tasse after he allegedly fought the Devil and came out relatively unscathed.

Perhaps the Devil didn’t come out unscathed and this sculpture depicts him hammering his leg back into shape, which a bunch of slightly tipsy workers swear they saw him doing at the forge one night.

And then there’s Mme. Poulin’s trunk. She was the daughter of François Poulin de Francheville, the founder of the Forges du Saint-Maurice and supposedly inherited a fortune from him when he died, which she put in this trunk. To make sure that nobody could open it, she threw the key into the Saint-Maurice River and to this day people still search for it at a place called the Devil’s Fountain.

Leaving the Grande Maison you make your way to the blast furnace.

This is what it looked like shortly after it was abandoned in 1883.

And this is the Parks Canada reconstruction on the same site.

Inside there are more interesting exhibits along with the 1600°C Trial by Fire which is an interactive 15 minute experience that will test your ability to keep up with the furnace master’s demands to keep shovelling!

If you don’t fancy continually stoking the blast furnace you could always become a limestone crusher, like this guy. Can you imagine doing this ten hours a day, six days a week?

This model gives one a better sense of the relationship between the blast furnace on the right producing pig iron from iron ore and the forge on the left where the pig iron was hammered or moulded into the many products produced over the 150 years that the Forgers du Saint-Maurice where in operation.

The blast furnace required a massive bellows to constantly fan the flames to keep the temperature up.

And a waterwheel to keep it fanning.

Beside the blast furnace are the remains of the upper forge.

From here you follow a path along the stream to the lower forge which has been partially reconstructed.

Compared to archaeological sites I’ve visited around the world, the Forges du Saint-Maurice is a relative baby, but that’s more than offset by the fact that it’s in Canada where industrial archaeological sites are virtually non-existent. Standing here looking at this forge, I try to imagine the hundreds of workmen and their families that once made this one of the most important places in New France, then Lower Canada and finally the new nation of Canada. It reminds me that something that once seemed permanent, was not, but that does not mean that we, as a nation, should forget the contribution to our country this place and others like it made to our history and our fabric.

As I return to the near empty parking lot, I have to wonder why more Canadians are more interested in staring at their smart phones in some kind of digital trance, affixed to whatever app they are using, when they could be experiencing something much more tangible by visiting a place like the Forges du Saint-Maurice.