Volubilis – Morocco’s Roman World Heritage Site

This is my fourth post from the recently completed Quintessential Morocco Tour by Adventures Abroad. The first post was an overview of the entire trip, explaining why Morocco is a great destination and why Adventures Abroad is a great choice to lead the way. The second post featured Casablanca and the last post the capital city of Rabat, which was the first of many UNESCO World Heritage Sites we visited on this tour. In this post we’ll visit another World Heritage Site, the ruins of the Roman city of Volubilis. It promises to be another great day in this fascinating country.

History of Volubilis

Although ostensibly a Roman site, Volubilis is actually much older than the Roman period of occupation that did not begin in earnest until just before the 1st century. It has a location on a ridge above the fertile Khoumane River valley with streams coming down from Zerhoun mountain that overlooks the site. The photo above from the official website illustrates that very well. In other words, the combination of a good water supply and for Morocco, fertile soil, made it a natural place for human settlement. Neolithic pottery dating back 5,000 years has been found in the area. As with most northern Moroccan archaeological sites, it was the Phoenicians who first made Volubilis into a permanent settlement in the 3rd century BCE and their protégés, the Carthaginians who really made it into an important agricultural and trade centre. Remains of a temple to the god Baal have been found outside the Roman area of occupation. Biblical scholars will remember the clash between Elijah representing the Hebrew god and 450 prophets of Baal on Mount Carmel that resulted in a TKO of Baal and a triumph for the Hebrew god.

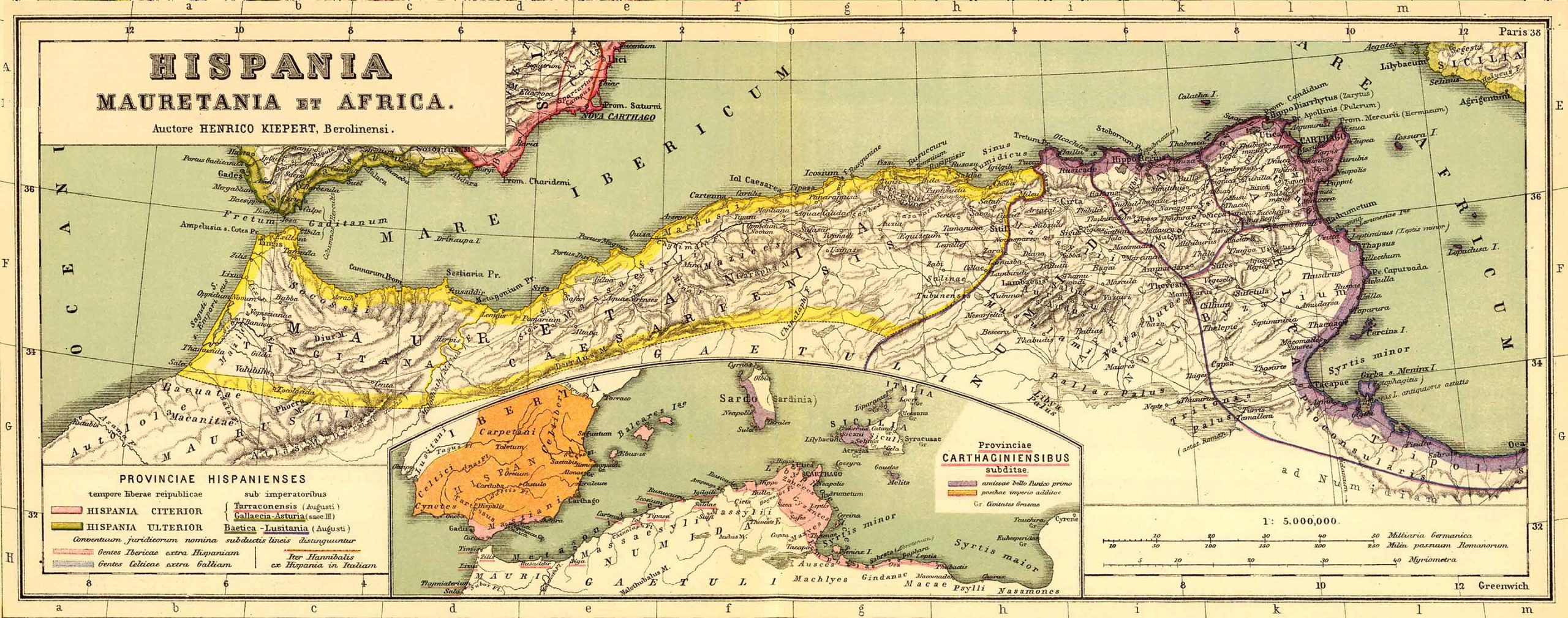

After the Romans defeated the Carthaginians once and for all in the Third Punic War that ended in 146 BCE, Volubilis, which was located in what became the Roman client state of Mauretania, was now ruled by Berber kings who owed their allegiance to Rome. As this map shows, the Roman state of Mauretania, outlined in yellow, was nowhere near the modern country of Mauretania which lies some thousand kms. or more south of the original Mauretania. The Romans referred to the Berbers of the area as the Mauri which in turn evolved into the term ‘Moor’ and hence, Morocco.

Things really got interesting at Volubilis when Emperor Augustus appointed Juba II ruler of Mauretania in 25 BCE. While he was a Berber prince from Numidia, the province next door to Mauretania, that included parts of modern Algeria, Tunisia and Libya, it was his wife and co-ruler Cleopatra Selene II who was the real star of the show. She was the only daughter of Cleopatra VII, the one we just call Cleopatra these days and famously depicted by Elizabeth Taylor in the movie of the same name. Her father was Mark Antony, portrayed in the movie by Richard Burton. Together they sparked one of the most infamous relationships in Hollywood.

After Antony and Cleopatra were defeated in the final Roman civil war by Octavian, who became the first Roman Emperor Augustus, Cleopatra Selene was taken to Rome and raised in the extended royal household by Octavia, Augustus’ older sister and former wife of Mark Antony before he divorced her to be with Cleopatra. Rather than being the spiteful step-mother you might expect, Octavia treated Cleopatra Selene very well and was the one who arranged the marriage with Juba who was also raised in Rome, first in Julius Caesar’s household and after his death, in Augustus’.

Thus in 25 BCE this superstar couple were sent to Mauretania to take charge and although Caesarea in modern day Algeria was the titular capital, they chose to make Volubilis the most important city in the territory. Together they embarked upon creating a thoroughly Romanized city far from their childhood home. In the year 40 the bastard Caligula had Juba and Cleopatra’s son Ptolemy assassinated which set off a revolt in Mauretania which the Romans crushed. Emperor Claudius, successor to Caligula, annexed Mauretania as a Roman province and for the next 200 years the city prospered, reaching a population of about 20,000 at its zenith, most of whom were Romanized Berbers.

In 280 Roman control over Mauretania collapsed except for a narrow band along the Mediterranean. Volubilis continued to survive over the next few centuries and even had a small Jewish population. It was still occupied when the Arabs invaded the area in 787 and in fact was the city that Moulay Idriss, the founder of Islam in Morocco, chose to make his capital. It was here that he was assassinated in 791 on orders from the Caliph of Baghdad. After his death, his son Idriss II, who was born in Volubilis, moved the capital to Fes which his father had founded a few years earlier. Volubilis then entered a long period of decline with the ultimate insult being the removal of the tomb of Idriss I to the nearby town of Moulay Idriss Zerhoun where a huge mausoleum was built which you can still visit today. The final straw was the Great Earthquake of Lisbon in 1755 which flattened most of what remained of Volubilis.

While amateur archaeologists had been poking around and looting Volubilis from the time the French first appeared in the area in the 19th century, it was only during the French Protectorate that serious efforts at restoration got underway. The French actually wanted to use the resurrection of Roman ruins as a symbol of the Europeans ‘right’ to dominion over what they viewed as less advanced races. Fortunately this archaeological colonialism did not put off efforts by the independent Morocco to continue to restore the site and in fact most of what we will see on this visit dates from post independence.

In 1997 Volubilis was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site with this brief synthesis:

Volubilis contains essentially Roman vestiges of a fortified municipium built on a commanding site at the foot of the Jebel Zerhoun. Covering an area of 42 hectares, it is of outstanding importance demonstrating urban development and Romanisation at the frontiers of the Roman Empire and the graphic illustration of the interface between the Roman and indigenous cultures. Because of its isolation and the fact that it had not been occupied for nearly a thousand years, it presents an important level of authenticity. It is one of the richest sites of this period in North Africa, not only for its ruins but also for the great wealth of its epigraphic evidence.

So with that background let’s visit Volubilis.

Not far from the site there is a pullout where we stop for this view of the valley below and the reservoir Barrage Sidi Chahed in the distance.

These turn outs usually have people selling local handicrafts at very reasonable prices; for example these colourful hot pads which several members of the group snapped up.

We arrive at Volubilis in the late morning and there are already at least a dozen, if not more, large tour buses in the parking lot which is almost completely full. If at Rabat I had visions of almost deserted ruins, that is completely shattered at Volubilis. However, the site is large enough that it can accommodate large numbers without feeling overcrowded.

We were fortunate to have a very knowledgeable and engaged local guide, Alaj who helped bring the site to life in the 90 minutes or so we spent exploring Volubilis.

There are any number of different paths you can take to see the ruins of Volubilis so there’s no definitive route that every guide follows. Alaj took us on a route that avoided most other groups and still made sure we saw all of the highlights. I will now feature some of the most notable and then come back to the mosaics which I thought were outstanding.

You enter the site from below and gradually make your way up to what at first appears to be just a jumble of ruins. Before we got there pretty well everyone in the group stopped to get the quintessential Volubilis photo.

And this is the jumble of ruins.

But with the experienced eye of Alaj you begin to see details that help you imagine daily life here some 2,000 years ago. For example, the semi-circular marks on this threshold that were made by the door hinges over God knows how long.

Or this olive press, one of over thirty on site that reveal the significance of Volubilis as a centre for the production of olive oil.

Then Alaj pulls a real shocker, pointing to a beautiful cypress tree, he says, “Here’s something most of you have seen before.” How is that possible, none of us have ever been here before?

According to Alaj, this particular tree appears in a scene in the movie Gladiator. While I was unable to confirm that, I did confirm that Volubilis stood in for the city of Zucchabar in the movie and the ground we are standing on was definitely part of the movie. This will not be the last time on this trip that we come across places in Morocco where that illustrious movie was filmed.

We are now at the main street of Volubilis, the Decumanus Maximus which was once paved and lined with shops. This is the view looking north to the Tinger Gate from which you could take a Roman road directly to Tinger (modern Tangier).

This is the view looking south to ward the Triumphal Arch of Caracalla. Note that even with hordes of visitors it is possible to get photos that make the place look almost deserted.

While you can’t see it from these photos, there was a ground level aqueduct fed by a mountain spring that brought clean running water to most of the shops, houses and fountains of Volubilis. This solarium in the House of Orpheus was once a private bathing area where you could sit in the open air taking in the sun’s rays while dangling your feet in cool water.

The Arch of Caracalla was built in 217 by the city’s governor Marcus Aurelius Sebastenus to honour the emperor Caracalla who had both Punic and Arab blood in his genes. In 212 he issued the Constitutio Antoniniana that gave Roman citizenship to all free men living anywhere in the Roman Empire. This was a momentous occasion for anyone living outside of Italy including the citizens of Volubilis. There once was a six horse bronze chariot on the top and medallions of Caracalla and his mother Julia Domna on each side of the arch. Unfortunately for Caracalla, who other than this one grand act, was not much better than Nero or Caligula, he was assassinated before the arch was finished.

There are two other grand public buildings in Volubilis besides the Arch, the basilica and the Capitoline Temple.

The basilica was completed in the early 3rd century during the reign of Macrinus, the guy who had Caracalla murdered and the first and only Berber emperor. While we tend to think of basilicas as religious structures, in Roman times they were administrative and judicial buildings that were often the most important in any community. Christians later adopted the traditional shape of basilicas with a nave, side aisles and an apse for their own early churches.

Once again, by showing some patience and the proper angle I was able to get this photo of the Volubilis basilica without other tourists.

The other major public building of Volubilis is the Capitoline Temple for which I have chosen to use this public domain photo to give a better idea of its layout.

According to an inscription found on site, it was constructed in 218 and dedicated to the three most important Roman gods, Jupiter, Juno and Minerva. At the base is an altar where sacrifices to these gods were made in the hopes of guiding the citizens of Volubilis in making important decisions, such as whether to start a war or make a peace treaty.

The capitals on the top of the columns are in the ornate Corinthian style with acanthus leaves and scrolls that were very popular during Rome’s heyday.

We concluded our visit to Volubilis with this group shot from the steps of the Capitoline Temple – all hail Caesar!

However, as promised at the beginning of this post I am now going to focus on what I thought were the highlights of the visit to Volubilis, the mosaics. Volubilis had a number of very grand homes that have been excavated revealing some of the best mosaics to be found in all of North Africa. I’ll describe a few of them in roughly the order we came across them.

I am using public domain photos for most of these as photographing them in the direct light of a Moroccan sun is not easy.

From the House of Venus, this is the myth of Diana and Acteon, a hunter who had the misfortune of coming across the goddess at her bath and for his reward was turned into a stag, which his own hunting dogs then tore to pieces. Acteon is not actually depicted being destroyed, but any contemporary would know what was about to come..

Also from the House of Venus is this much lesser known Abduction of Hylas. Hylas was a companion of Hercules. While sailing with Jason on the search for the Golden Fleece Hylas was sent ashore to collect fresh water and a group of Naiads, water nymphs, were so captivated by his beauty that they seized him and dragged him under never to be seen again. Hercules was so upset that he quit the Argo to search for Hylas, all in vain. As far as I could tell this is the only famous mosaic anywhere depicting this scene.

One of the best mosaics at Volubilis depicts the Four Seasons, a common theme in Roman homes. The colours are still bright after 1,800 years.

However, there is one mosaic that stands out above all others at Volubilis and that is the Labours of Hercules found in the dining room of a house that had 41 rooms. This is my own photo as are the close ups that follow.

Hercules or more properly Heracles was the son of Zeus and Alcmene, a mortal woman who Zeus seduced when he appeared in the guise of her husband Amphitryon. Hera, Zeus’ wife hated the child and sent snakes to his crib to kill him. This scene is depicted in the mosaic even if not one of twelve labours.

Still pissed at Heracles after decades, Hera drove him mad and he killed his wife and children. In repentance the Oracle at Delphi ordered him to serve the Mycenaean king Eurrytheus for ten years and do his bidding which included this increasing difficult series of labours, all of which are depicted in this mosaic.

Here he is capturing the Cretan bull.

And killing the Stymphalian birds, which looks more like a cake walk than an actual labour.

And his 12th and final labour, bringing back Cerberus the three-headed hound of hell back from Hades, who seems rather docile.

These particular mosaics are not great works of art like most of the others at Volubilis, but they do tell an interesting story that has captivated people since it first appeared in a lost work by Peisander of Rhodes over 2, 700 years ago.

One final piece of the Hercules mosaic that is notable.

Yes, that’s a swastika, which for untold millennia was a symbol of good fortune in both the Old and New World until the Nazis defiled it so that now it is a symbol of hate. Many people are not aware of the ancientness of this symbol and are often surprised to see it depicted in the art of many cultures around the world.

Well that concludes our trip to Volubilis and thanks to Alaj it was a great experience. Next we’ll make a short visit to another World Heritage Site, the city of Meknes. I hope you’ll join us.