Fes – Morocco’s Most Interesting City

The Quintessential Tour of Morocco with Adventures Abroad is truly underway. In just three days we have visited three UNESCO World Heritage Sites, Rabat, Volubilis and Meknes with more to come as we move on to the ancient imperial city of Fes. However, before visiting the world’s largest medina for which the city is famous, we need a little history lesson that will help us appreciate what we are about to experience.

History of Fes

This is an overview of the Fes medina from a point in the hills that surround the city. The singular white minaret marks the site of the mosque and madrassa founded by Fatima al-Fihri in 857 which is often described as the world’s oldest university. Although in fact until 1963 when it was incorporated into the state system it was technically not a university, both UNESCO and The Guinness Book of Records recognize it as the oldest institution of higher learning in the world. The scholars who studied and taught here included some of the greatest names from the Golden Age of Islam which is considered to have lasted from the 8th to the 13th century. What is truly extraordinary about them was that they included not only Muslims, but Christians and Jews as well.

Here are few of the most famous scholars associated with Fes.

Ibn Rushd, who westerners know as Averroes, was one of the greatest polymaths the world has ever produced. Author of over 100 books he was known as “The Father of Rationalism” and the man who reintroduced the world to the works of Aristotle 1,400 years after his death.

Gerbert of Aurillac who became Pope Sylvester II, was a great believer in Moorish mathematics and astronomy and introduced the decimal numeric system to the Christian world.

Maimonides was perhaps the greatest Jewish scholar of the Middle Ages; after being expelled from Spain he became the personal physician of Saladin, the greatest thorn in the side of the Crusaders.

And my personal favourite, the great world traveller Ibn Battuta who racked up over 117,000 kms, (73,000 miles) in his journeys through Africa, Asia and Europe during his lifetime, almost five times as much as the much more famous Marco Polo. Even Adventures Abroad’s Martin Charlton would be envious of Battuta’s feats considering he accomplished them mostly on foot or on a camel.

I raise the university at this point because once you are inside the medina it is next to impossible to separate it from other structures and non-Muslims are not allowed to enter the mosque which was the foundation of the institution.

Now back to Fes.

First of all it’s Fes and not Fez. The latter is an Anglicized version used only by English speakers, but it is the right name for the hat.

It is only fitting that we have already visited the Roman site of Volubilis on this tour. It was from here that Idris I, the first Arabic conqueror of Morocco in 789 founded the city on the east bank of the Oued Fes, a river that flowed out of a limestone outcrop some 12 kms. (7 miles) above the new settlement. Later in 809 his son and successor Idris II founded a competing settlement on the west bank of the Oued Fes. Although he like his father, died in Volubilis, he was interred in a mausoleum in Fes that is now considered the holiest shrine in the city. We will get a peek at it on our tour of the medina.

Over the next few centuries Fes became a magnet for Arabs emigrating from Tunisia and Andalusia and became the de facto Arabic city in Morocco. If you’ve read my previous posts from Rabat and Meknes you will know that a familiar story will be retold in Fes as it was in those places – constant changes in dynastic control over hundreds of years. In the 11th century the Almoravids conquered Fes and consolidated the towns on both sides of the river into Fes el-Bali or the Old Quarter. This is what evolved into today’s Fes medina. After a prolonged siege, the Almohads took over in 1146 and moved the capital to Marrakech. Even so, by the 12th century Fes had grown to a city of over 200,000, by far the largest in Morocco.

In 1248 it was the Marinids turn to take over Fes and they restored the city’s status as capital. More importantly, they founded a completely new settlement outside the existing walls, Fes el-Jdid or New Fes and constructed a royal palace there that is still in use today. This new city also became the centre of Jewish occupation as we shall see.

Fast forward five hundred or so years and Fes is still the preeminent city in Morocco, although it is in a slow decline as it is, in essence, a medieval city within a modernizing industrial world. The French arrive in 1912 and move the capital to Rabat and begin building yet a third city outside the areas occupied by Old and New Fes. This is the Villes Nouvelles and is where the Europeans live, leaving the older city virtually intact which is why in 1981 it became a UNESCO World Heritage Site with this description of the medina:

The Medina of Fez is considered as one of the most extensive and best conserved historic towns of the Arab-Muslim world. The unpaved urban space conserves the majority of its original functions and attribute. It not only represents an outstanding architectural, archaeological and urban heritage, but also transmits a life style, skills and a culture that persist and are renewed despite the diverse effects of the evolving modern societies.

Today Fes is the second largest city in Morocco with a population of 1.1 million of whom around 15% still live with the walls of the medina.

Riad El Yacout

Before heading out to explore Fes, a few words about the Riad el Yacout where we spent three nights. There are two types of dwellings within the confines of a medina. By far the most common is the ‘dar’ which simply means a house and is where most of the middle class residents of old Fes reside. Far more palatial, literally, is a riad, which were the homes of upper class merchants and nobles. The name means ‘garden’ and every riad features an inner atrium, water, greenery and many different rooms. In places like Fes and Marrakech few of these riads are still private homes, but rather have been turned into boutique hotels. Such is the case with the Riad el Yacout. Built in the 16th century for a renowned professor at the university, in 2000 it was transformed into a luxury hotel.

The thing about riads is that they do not have any external openings except the entrance. All you see from the outside is a wall. Our guides repeatedly assured us that this was because the owners were modest and did not want to flaunt their wealth by being overtly ostentatious. Hmmm.

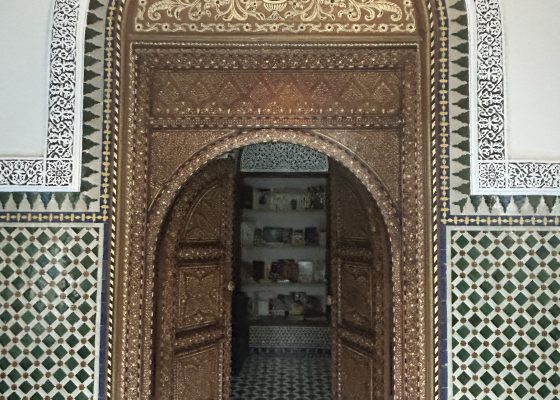

In the case of the Riad el Yacout you have to go down a narrow lane and then into an even narrower alley to find the entrance. Only a dimly lit sign gives any indication that this is a hostelry of any sort. However, once past the huge wooden door you enter a totally different world. It is the attention to detail in the craftsmanship of the interiors that makes these places special. Here is a small gallery of some of those details. Double click to open a photo and double click again to enlarge.

A word about the rooms in riads – they differ dramatically in size and decor. While some in the group got huge suites, others, like Alison and I got very small rooms that bore no resemblance to any of the photos on the website. Over the course of the trip we were the beneficiaries of great rooms in other riads and not so great in others. It tends to even out.

Ok, at last we are ready to visit the medina of Fes. Wait, not so fast. Our first visit of the day was to the lookout spot from where I took the header photo. Outside the medina there is an area where there are a number of small workshops where two of the city’s most famous crafts are made, Fassi pottery and zellige mosaic tiles. We stop here, not necessarily to buy, but to observe and learn how these crafts are made, starting with the pottery.

Fes or more properly Fassi pottery dates to the 15th century when both Arabs and Jews were expelled from Andalusia and gravitated to Fes, bringing with them their knowledge of complex pottery making that involved double firing and the use of cobalt to create the the distinct bright blue bowls and other items for which the city is famous.

The clay deposits around Fes are grey as opposed to the more traditional red clay that produces terra cotta pottery. Here is a potter shaping the grey clay using a potter’s wheel, a technique that goes back 6,000 years and still has not been marginally improved upon to this day. Watching this guy for about five minutes, he produced three perfectly shaped bowls.

From here the bowls are put into these traditional kilns for a first firing.

From here the pottery is taken to be painted by hand in one of the many traditional patterns before a second firing which will bring out the brightness of the cobalt blue and other colours.

And here are the finished products that Alison is checking out.

While I have visited potteries many times, I can say that the process of creating the intricate mosaics that are the signature feature of Islamic art, was new to me. It’s a complicated six part process that is done entirely by hand and in the case of Morocco, remains largely unchanged since the 10th century.

Mosaics first appeared in Mesopotamia over 5,000 years ago and gradually evolved over time. The first mosaics were made from shells, coloured stones and other things found in their natural state. The Greeks perfected the technique of using pebbles to create their distinct mosaics and the Romans took it a step further as we observed at Volubilis, using individual coloured pieces of glass or tile known as tesserae. The Byzantines took mosaics even further creating beautiful religious images out of gold and glass tiles.

The mosaics that developed in the Muslim world were a bit different in that they were made from tesserae that were fired from clay, dyed and shaped by hand into tiny patterns that were fitted together into intricate designs where the sum was literally greater than the parts. This technique, known as zellige, was pretty standard throughout the Muslim world up until the 15th century, when it was abandoned in all but Morocco where it remains the standard method of producing mosaic work today. We have seen modern examples at the Hassan II mosque in Casablanca and post 15th century examples at the Riad el Yacout.

Now we’ll observe the creation of zellige mosaics firsthand.

As noted it is a six part process that begins with using the same grey clay that is used in pottery making. It is kneaded by hand to remove air and then shaped by hand into square tiles that are dried in the sun. Then the tiles are fired in the same kilns we saw earlier after which they are glazed and fired again. Now we have tiles that are ready to be shaped into the special shapes that will be used to make the finished mosaic.

This is an incredibly time consuming and delicate art that takes years to master. You can see the square tiles that each artisan starts with. Then using a precision instrument called a menkach these maallems, as these master craftsmen are properly called, create tiny pieces that are then put together by another master craftsman.

Finally the back of the inlaid tesserae are coated with plaster to bind the whole thing together, then its flipped over and polished to bring out the vibrant colours.

There is not really a showroom for the mosaics like there is for the pottery, but I did see shipping crates ready to go with addresses all over the world.

At the time of the visit to this zellige workshop I did not appreciate what a rare experience this was, Fes being one of only a few places in Morocco where this ancient craft is still practised.

Okay, can we finally go to the medina? Sorry, but this post is already long enough and we’ll see you at the medina in the next post from Fes.