Ranville War Cemetery – Learn How to Find a Specific Grave

This morning we visited Pegasus Bridge and learned about the advance parachute, glider and commando operations that spearheaded the June 6, 1944 D-Day landings in Europe. While the operations were largely successful, they were not without significant casualties and many of these are interred at nearby Ranville War Cemetery. This is the first of many war cemeteries we will visit on Liberation Tour 2015 by Liberation Tours, a Canadian company specializing in the Canadian contributions to both world wars. Hopefully, using Ranville as an example, this post will help the reader understand how these war cemeteries are laid out, how to find a specific grave and learn more information about the individuals buried in them.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The first thing to know is that almost all cemeteries containing the remains of soldiers who served from British Commonwealth countries in both wars are administered by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, an organization proportionately funded by the major members of the British Commonwealth. Great Britain pays 70% of the cost, while Canada pays 10%. Australia and New Zealand also contribute.

Believe it or not, there are more than 23,000 cemeteries or memorials in 154 countries. Even more astonishing is that there are over 1.7 million men and women buried in them. I’ll repeat that – 1,700,000 war dead from the British Commonwealth in two world wars.

The Commission was first established in 1917 and laid down some early rules that are important. First, each of the dead must be commemorated by name if possible. Second, the headstones are permanent and will be maintained in perpetuity by the Commission. Third, all the headstones must be uniform. Fourth, no distinction can be made based on rank, race or creed. This is important, as in death, all are equal. A general gets no different a headstone than a private.

Also important is that every grave contains an actual body. Where the identity of the body is unknown it is indicated on the tombstone – that person becomes an unknown soldier.

Ranville War Cemetery

With this information imparted by tour leader John Cannon, we disembarked at Ranville War Cemetery. Almost all the Commonwealth cemeteries are laid out in a uniform pattern. There is one entry through an archway where you will always find two important documents inside a small metal container built into the side of the entryway.

The first is the Memorial Register which is an alphabetical list of names with the necessary information to locate the grave. Most cemeteries are divided into sections and then rows starting with A at the front. So you find the section, the row and then the number. The first thing I always do in looking at these registries is look for any Dunlops, and in the case of Ranville I found an A. Dunlop, buried in Section III Row B Grave 17. That will be my first stop.

However, before entering the cemetery proper there is another important book, the guest book. I think it is almost a duty to enter your name and address and any comments you wish to make. The fact that these boys and men are visited and remembered goes some small, very small, way to atone for the ultimate sacrifice they made. Here is my sister Anne signing the Ranville book.

The first thing I always notice on entering any Commonwealth War Cemetery and Ranville is no exception, is that the combination of the uniformity of the graves, the symmetry of the rows whether you look at them straight on or diagonally and the flowers, makes them beautiful. I know that might seem almost blasphemous, but I would much rather have beauty than despair.

Here is Ranville War Cemetery. I think it is wonderful, in the true sense of that word – it inspires wonder at how things could ever have come to this.

Another common feature of most Commonwealth cemeteries is the Cross of Sacrifice, which will be recognizable to most. It represents an inverted sword (aka pointing down) signifying that the war is over for these souls, as opposed to statues you see with people rushing into battle with their swords upraised. Somehow I overlooked taking a picture of the one in Ranville so I poached this from the web.

Another common feature is the Stone of Remembrance which is intended to commemorate those “of all faiths or none” . It was designed by famed British architect Sir Edwin Luytens and is simplicity itself.

Okay, time to find Mr. Dunlop’s grave at Ranville.

Here he lies. British graves always contain the regimental coat-of-arms, in this case the Seaforth Highlanders. It kind of sends chills down my spine as I have two sons who are A. Dunlop.

In addition to the information contained on the grave you can obtain more on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website by finding the cemetery and then the individual. In this case the entry for A. Dunlop on the Ranville site reveals that his first name was Archibald, not Alexander or Andrew as my sons are named and that he was the son of Archibald and Margaret Dunlop of Greenock, Scotland. You can also click a link to see his Commemorative Certificate.

There are a few Canadians in Ranville and now I’ll look for them. Here is an unexpected find.

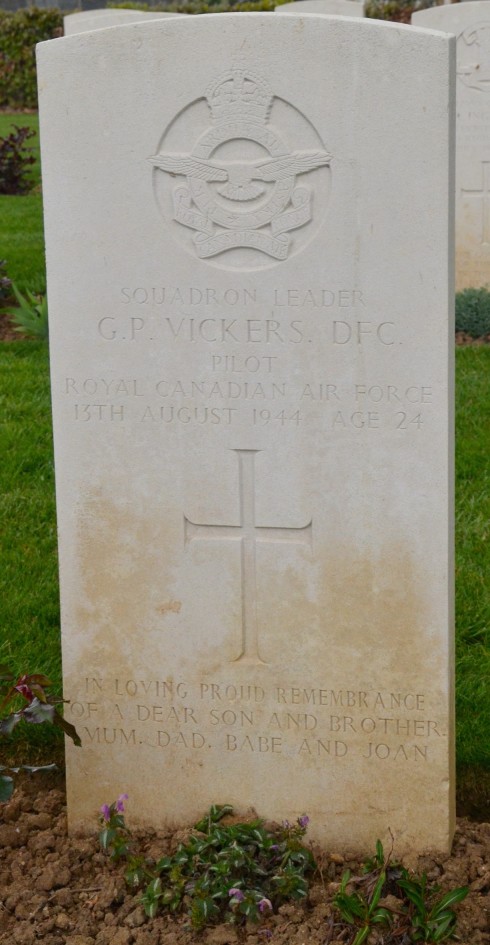

The very first Canadian I find at Ranville is a genuine war hero. This is George Peter Vickers from Vancouver, British Columbia who won the Distinguished Flying Cross. Note the inscription at the bottom – “In Loving Proud Remembrance of a Dear Son and Brother. Mum, Dad, Babe and Joan.” These tributes are optional on Commonwealth graves and are provided by the family.

I was able to find a little more information on Mr. Vickers on the Veterans Affairs Canada website, but unfortunately no picture.

Next I find French-Canadian J.E.A. Aubin of the 1st Canadian Parachute Division. He died on D-Day. Note that his gravestone has a maple leaf at the top. This is the common symbol for all fallen Canadians except members of the Royal Canadian Air Force, as seen on Squadron Leader Vickers’ grave. Searching the CWGC site I find his full name is Joseph Ernest Albert Aubin, but no further information. Searching further I come across the Juno Beach Centre site and find that Joseph grew up in Sturgeon Falls, Ontario, one of nine children, before moving to Montreal. He was working on a mechanics degree when he signed up in North Bay. Again no photograph, but I found this great link telling the story of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion and the fight for Varaville.

Here is the grave at Ranville of one of the few glider pilots who perished on D-Day, D.F. Wright.

His full name was Duncan Frank Wright and he was a son of Russell and Elsie Wright and husband of Mary Wright. A lot more information about Duncan Wright can be found on the Airborne Assault Paradata website and from the Pegasus Archive. It turns out that Wright survived the glider landing, was captured and murdered on D-Day by soldiers in the 711th Division of the German army. Again, I couldn’t find a photograph.

The last grave I’m going to focus on in this post is that of J.B. Wain a gunner in the Royal Artillery who died at age 18. His full name was James Bernard Wain and he was the son of James Albert and Annie Wain of Liverpool.

I noticed his grave in particular because of the thoughtful and moving inscription at the bottom, no doubt supplied by his parents. “Music, Mountains, Sun and Rain. Youth, Truth and Unity Echo For Ever His Name.” It makes you realize that he was a real person who had so much to live for and then on July 21st, 1944 he didn’t. No photo either.

It is not my intention to deluge the reader with stories and pictures from every cemetery we will visit on this trip, but hopefully to demonstrate that every known grave has a story to tell and that with the aid of the internet it is possible to know far more than was ever possible even a decade ago. I urge visitors to these cemeteries to seek out graves, whether it be because they share a common name, nationality or for any other reason and to try to find the story that’s contained in these headstones. Lest we forget.

Next Liberation Tour 2015 will reach the Normandy coast and we’ll learn the story of the disabling of the crucial batteries at Longues-sur-Mer.