Battle of the Somme – Two Stories out of the Million Who Died

After a very emotional morning at Beaumont Hamel, Liberation Tour 2015 moved a short distance away to the Ulster Memorial Tower which commemorates the more than 1,850 Ulstermen who died on July 1, 1916 the first day of the Battle of The Somme. It’s a handsome building which is a replica of Helen’s Tower, a well known landmark just outside of Belfast.

Battle of the Somme

The tower sits on relatively high ground from where we could look back and see the ground on which much of the Battle of the Somme fighting took place on that fateful day in July, 1916. The woods on the left mark the area where the Newfoundlander’s were ordered to attack and where almost 700 of them were casualties by 10:00 AM.

The tower and a small cafe and gift shop as well as Thiepval Wood, which we will be visiting shortly, are administered by the Somme Association which is based in Northern Ireland and dedicated to preserving the legacy of the Ulstermen who fought and died by the thousands at the Battle of the Somme. Today we had a nice set lunch with a really good squash soup courtesy of Teddy and Phoebe Colligan who have made it their life’s work to make sure that this place is kept up and open for visitors. Here’s tour leader John Cannon with the very modest and grateful Teddy & Phoebe.

Connaught Cemetery

After lunch we were joined by Matt Gamble a trained archaeologist and walked a short distance down the road to Connaught Cemetery where 643 men killed at the Battle of the Somme are interred. This was not our intended destination, but rather a small road behind a locked gate that led into the woods behind the cemetery.

Before entering the woods Matt pointed out a spot where the highway was slightly widened in 2013 and the remains of Sgt. David Blakey were discovered by highway workers. He had been one of the disappeared for 98 years, but now was at last going home to a final resting place in England. This was the first of the stories on this walk that brought home to us the personal lives of individual soldiers and their fates.

Thiepval Woods

Thiepval Woods is a privately owned piece of very nice forest that has grown up since WWI. In July, 1916 there were no woods here, but rather front line trenches that have since grown over, collapsed or otherwise been forgotten. The purpose of the association which looks after the area is to undertake excavations of the trenches and tunnels using modern archaeological methods to get a better understanding of what it meant to live, breathe, eat, sleep and die here.

We were joined on the walk by Pvt. Hunter Alliston who was dressed in the full regalia of the tommies who were actually in these trenches at the Battle of the Somme.

Here is Matt with Hunter pointing out the features of this excavated trench which is authentic in every way.

This is exactly where the Ulsterman were positioned on July 1, 1916 when they were ordered to attack.

Here is an example of the very first type of gas mask issued to soldiers after the Germans first used poison gas at the 2nd Battle of Ypres in 1915, which was also the first major Canadian engagement of WWI. Both sides had used non-poisonous gas, similar to tear gas before this, but it was the Germans who ramped it up to lethal intensity. It looks more like something that a horror movie villain would wear than anything that might save your life. However, excavations at this site have found gas cylinders with the gas still intact so it might be a good idea to keep one handy.

After showing us around the trenches and pointing out partially excavated tunnels, underground rooms and mortar positions, that were all part of the Battle of the Somme, Matt brought out this ordinary looking spoon with a bullet hole in it. Doesn’t sound like a big deal right? Except it is.

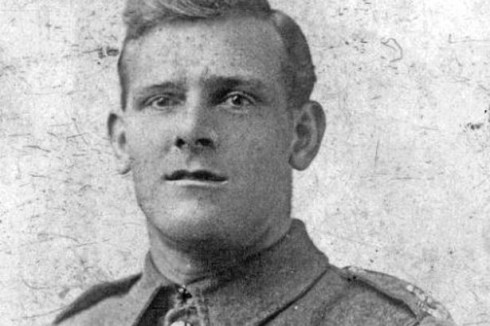

The spoon had WWR 19982 marked on it. Research indicated that this was the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment from West Riding Yorkshire and the number identified the owner as John W. Hatfield. Medical records indicated that Hatfield had been shot in the leg while serving here in 1916, but what’s that got to do with the bullet hole? Well as it turns out, the soldiers kept their spoons tucked into their puttees which are cloths the soldiers wrapped around their knees. Have a look at Pvt. Alliston again, he is wearing them.

So in a war where all wounds could lead to death, that spoon might have saved John Hatfield’s life and no doubt got left behind as the medics treated his wound, only to resurface almost a hundred years later and tell one of the few good news stories from the Battle of the Somme.

Next we head to the Thiepval Memorial which commemorates the 72,000 men who simply disappeared during the Battle of the Somme. It will leave you shattered.