Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park, Florida

This is the next entry in my ongoing series on Florida State Parks or ‘The Real Florida’ as their motto states. The more of these parks I visit the more inclined I am to agree that the motto is dead on. A couple of examples in this series include Myakka River State Park and John D. MacArthurs Beach State Park. I had just dropped off Alison and Mica (our 16 year old miniature poodle) at the Orlando airport and was headed to Miami Beach for the night. I hauled out my Florida map and looked for something interesting in between the two places. Just north of Lake Okeechobee I saw a large green area marked Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park. Looking it up on the internet I knew I had found my destination and was off. Please join me and I’ll explain why you need to visit this awesome place.

People familiar with the word Kissimmee usually associate it with the small city of the same name just south of Disney World. However the Kissimmee River, which arises not far from the city, is really the starting point for the drainage system that eventually ends up in the everglades after passing through Lake Okeechobee. It drains an area of 3,000 square miles (7,800 sq. km.) and the Kissimmee Prairie Preserve is part of that system, many miles away, literally and figuratively, from the artificial world of The Magic Kingdom.

Most tourists come to Florida for the sun, the beaches and the theme parks. I’m not one of them, although I do love the sun and beach combing. There is so much more to Florida than just these attractions that very few tourists know or to be fair, care about. Those who do know Florida and its various ecosystems, certainly would think about the mangrove coasts, the everglades, the cypress swamps and the pine forests, but prairies? Not many I think. The Kissimmee Prairie Preserve protects an enormous 54,000 acres of the dry prairie that once covered much of central and south Florida. Today there is less than 10% of it left.

History of Kissimmee Prairie Preserve

Dry prairie is a knee-high grassland interspersed with sloughs and occasional live oak and cabbage palm hammocks. When the Spanish brought cattle to Florida in the 1500’s the dry prairie proved the perfect place for the bovines to flourish. Just as the western prairies had proved the perfect ecosystem to sustain massive herds of bison, so too the Florida prairie for cattle. By the time the Spanish left there were hundreds of thousands of wild cattle roaming throughout the future state. These cattle attracted the Florida crackers, who came down from the north and made a career out of rounding them up and driving them to market, accompanied by the distinctive crack of their whips and thus their nickname.

Then came two groups that eventually led to the destruction of most of the dry prairie. One was the organized cattle rancher who fenced in much of the prairie and converted it to the grasslands that we see today throughout much of central and south Florida. The other group were the land speculators who bought up the prairie for pennies an acre and tried to convert it into Florida dream home lots for northern suckers. The reality is that the dry prairie is, in terms of actually living in it, a hot, dry and to most, desolate place far away from the beaches. As you drive the long road into Kissimmee Prairie Preserve you can still see signs advertising lots for sale along the way. Nobody seems much interested.

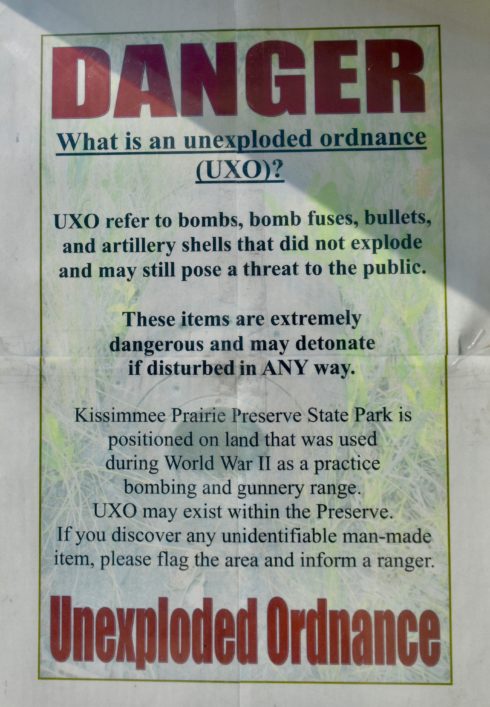

During WWII the U.S. military perpetrated the final insult on this ecosystem when it used it as a bombing range -a classic case of thinking that prairies are nothing but flat, worthless wastelands. Ironically, that final use is what probably saved the dry prairie from further exploitation as it was littered with unexploded ordnance. In 1997 the state bought 44,000 acres and started the process of restoring the dry prairie by filling in canals built by previous owners. These canals had prevented the spread of the naturally occurring wildfires that are essential to the maintenance of a healthy prairie. Some twenty years later the acreage has been upped by another 10,000 acres and the land is well on its way to healing itself. I am always amazed at how quickly an ecosystem can be restored if there is a proper understanding as to what it takes to make it thrive and what practices need to be avoided. So let’s go visit Kissimmee Prairie.

Visiting Today

Kissimmee Prairie Preserve is at the end of State Road 724. The closest place is the wonderfully named, Yeehaw Junction and there’s nothing there and not much in between the two. By Florida standards, this is the middle of nowhere. The pavement ends at the park entrance where you’ll find this signboard.

And this one. Pretty good reason to stay on the marked trails.

The entry fee is $4.00 and is on the honour system. Unlike many Florida State Parks, there is nobody manning a gated entrance to enforce payment. That’s usually a sign that there aren’t many visitors and I sure haven’t seen much vehicular traffic over the last twenty miles.

The visitor centre is five miles away on a dirt road with a speed limit of 25mph which is fine because it gives me a chance to look for two of the birds that have drawn me here – the crested caracara and the burrowing owl, which are both native to the park. Unfortunately, I see neither, but I do see swallow-tailed kites, a marsh harrier, red-shoulder hawks and meadowlarks. I see one car parked at a trailhead. There are signs of more people at the visitor centre where there are two campgrounds with RVs and tents set up underneath live oaks. The visitor centre is tiny and manned by one young woman who is helping two birders, anxious to spot a caracara. While I’m waiting I look around and notice a nice selection of T-shirts and other souvenirs, including a pin with a Carolina parakeet on it which I will definitely buy.

What’s this place got to do with the extinct Carolina parakeet? That’s what I was about to find out.

The Carolina Parakeet

As a life long birder I have been familiar with the story of the Carolina parakeet since I was a kid. The only parrot species native to the United States, it once abounded by the millions throughout the United States from Wisconsin to New York and throughout the southeast. Like the passenger pigeon it had flocking habits that made it easy to kill and that is what we did until there were no more left, anywhere. Here is James Audubon’s portrait of the Carolina parakeet.

And here’s a real one from the Field Museum in Chicago, albeit mounted by a taxidermist.

Can you imagine how much better off we would be today if our forests were alive with the sights and sounds of this gregarious, intelligent bird? But no, we were too stupid and too selfish to let these innocent creatures have at least one place on earth to live. Sad and tragic, but what’s this got to do with Kissimmee Prairie? A lot. The last wild Carolina parakeet was shot near here in 1904. Out back of the visitor centre is this beautiful statue by Todd McGrain.

It is part of the Lost Bird Project which places McGrain’s sculptures near the spot where the bird was last seen in the wild. It’s the subject of a film that showcases the spots where the passenger pigeon, heath hen and Labrador duck were last seen. And lest as Canadians we get smug because all these places are in the U.S. there is one more – the great auk and that sits on Fogo Island, Newfoundland.

The Carolina parakeet officially became extinct when Incas, the last of the species died at the Cincinnati zoo on February 21, 1918. By an incredible coincidence he died in the same cage that Martha, the last passenger pigeon had died in four years earlier. So I came to Kissimmee Prairie to find a caracara, which I never did see, and instead found the Carolina parakeet. I had to wipe away tears before reentering the visitor centre.

Biking the Kissimmee Prairie

There are over 100 miles of multi-use trails in Kissimmee Prairie Preserve. You can hike, bike or ride a horse over them and I did see people unloading horses to do just that. There is even a designated equestrian campground. Given the fact this was a hot dry prairie with not a lot of shade and the distances were far, I elected to rent a bike. For the princely sum of $2.00 an hour you can rent a multi-speed mountain bike with good tires and suspension.

The lady in the center advised me that the place had been hit by a tornado on April 6, just two weeks before my visit. For this reason a lot of the trails had not been cleared, but that there was a cleared section that ran out six miles and back which was a perfect distance for me on a mountain bike. I set out and it didn’t take long for the feeling of melancholia that had come over me to dissipate as I felt the breeze on my face and pedalled through a number of different ecosystems starting with this live oak forest. As you can see the trail was a bit sandy in places, but overall the riding was great – relatively flat, but with enough roots and tornado debris to skirt to make it interesting.

Here is a live oak limb broken off by the tornado.

Cycling on this path through the Kissimmee Prairie Preserve was exhilarating. I met only one other person the entire time. If you know where to go, it is quite possible to find solitude in Florida despite the fact that it now has over 21 million residents and God knows how many tourists.

The prairie was interrupted twice by hammocks which made for a grateful break from the relentless mid-day sun.

I know there are lot of people who think of prairies as dull, flat and lifeless. Nothing could be further from the truth. Kissimmee Prairie has literally hundreds of species of birds that can be spotted and even more types of wildflower of which these are but a few.

The person I met on the trail came upon me as I was taking a picture of a flower and he advised that because of the drought the number of flowers on display was minuscule compared to what it would be after some serious rain. I can only imagine, because it was pretty good today.

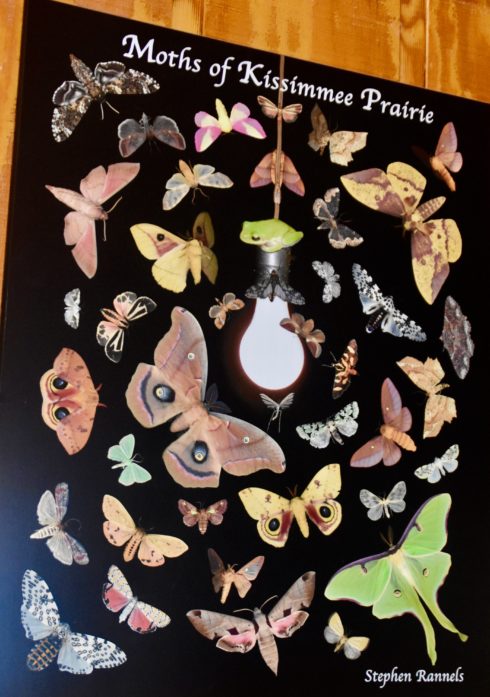

If you are a lepidopterist leave your net at home, but by all means head to Kissimmee Prairie to find some of the many species of moths that inhabit the area, as attested by this poster inside the visitor centre.

Kissimmee Prairie at Night

Speaking of moths, there is another reason to visit Kissimmee Prairie at night. On a full moon it is bright enough to walk the trails without a flashlight. It is also the first place in Florida to be designated a Dark Sky Preserve by the International Dark Sky Association which recognizes the need to preserve places from light pollution so people can actually see what the night sky is supposed to look like. Here is Florida from space at night. Pretty bleak, but with some good patches within the south interior.

Here’s a shot taken at Kissimmee Prairie at night. Besides planets, moons, stars and galaxies you can see the International Space Station.

Here’s the telescope Kissimmee Prairie keeps to assist aspiring astronomers.

So that’s Kissimmee Prairie Preserve in a nutshell. It really is an awesome place. To almost paraphrase Dean Martin in a song currently being used to promote VWs.

Let me tell you ’bout the birds and the bees,

And the flowers and the trees

And the moon up above

And I think of Kissimmee Prairie!

If you are interested in getting our in the everglades in a canoe check out the 5.5 mile trail in Loxahatchee National Wildlife Reserve – just don’t do it during alligator mating season as Alison and I did.