Fort Levis No. 1 – Beware the Americans

This is the third of four posts I am writing about lesser known National Historic Sites in Quebec. The first featured Grosse Ile and the Irish Memorial while the second focused on the remains of Chateau Saint-Louis underneath Dufferin Terrace in Quebec City. In this one I’ll cross the St. Lawrence River and visit Fort Levis No. 1, one of three built in the 1860s when the fears of an American invasion were very real. In light of current events perhaps a lot more people should consider visiting this virtually unknown National Historic Site.

History of Fort Levis No. 1

I suspect that many Canadians and probably most of our recent immigrants who never took Canadian history in school, assume that our relations with our southern neighbour have always been affable and mutually beneficial. Certainly that has been the case for about the last 150 years, until recent events have brought that assumption into question. However, there have been periods in our history when what was then a British colony and the United States have not only been hostile, but outright belligerent. In 1775 at the outbreak of the American Revolution the rebels made an ill fated attempt to capture the colony of Quebec and got their asses kicked outside of Quebec City on December 31st with the leader of the expedition, General Richard Montgomery killed on the battlefield and over 400 Americans captured. In the War of 1812 there were many battles fought on Canadian soil including the Battle of Fort York which I wrote about in this post and I’ll come back to later in this post. In future, I plan to do a series on the National Historic Sites related to the War of 1812.

In 1861 the American Civil War broke out and immediately severely tested the relations between Britain and both the north and south sides of that dispute. Britain relied almost entirely upon American cotton from the slave states for their textile mills that were a backbone of the economy. The Brits declaring neutrality, still had to walk a delicate tightrope between both sides. First the Union blockaded Confederate cotton shipments to Britain forcing it to obtain cotton from India and Egypt which enraged the Confederacy. When they attempted to send a delegation to Britain and France hoping for support and recognition the Union boarded the ship they were on and seized the Confederate diplomats in what became known as the Trent Affair, named for the ship upon which the Confederates were passengers. Up until Abraham Lincoln released the diplomats after a few weeks it looked like war between Britain and the Union was inevitable. Even after things simmered down, Britain sent 11,000 troops to Canada and decided to build a series of forts to guard the southern approach to Quebec City on the highest point of land on the south side of the St. Lawrence at Levis.

One of the main concerns was a railway line that had been constructed from Portland, Maine to Richmond, Quebec which linked into the existing Grand Trunk Railway. Theoretically it would be possible for the Americans to use this railway to freight troops and artillery to the outskirts of Quebec City in a matter of days. Fort Levis No. 1 and its two counterparts were specifically built to counteract this possibility.

Assistant Inspector General William Drummond Jervois was dispatched from England to design and build a series of five forts to guard the port of Quebec City. Ultimately only three were built in a broad 1,800 metre semi-circle of which only Fort Levis No. 1 survives today. Fortunately, none of the three Levis forts ever had to fire a shot in anger and the American menace never materialized. Like the more famous Halifax Citadel, which also never came under enemy fire, it will never be known if the fortifications acted as a successful deterrent or we were just lucky. The Treaty of Washington signed in 1871 which included Sir John A. MacDonald as a commissioner and signatory, ended a number of outstanding issues between Britain, the United States and Canada, supposedly for good.

Fort Levis No. I is located on the highest piece of ground on the south side of the St. Lawrence River just to the east of Quebec City. You actually look down at the city from the fort’s terreplain aka top of the ramparts. Getting there you pass by the Parc de la Paix in Levis where the engineers and later the soldiers who manned the fort were encamped. There is a CF 101B Macdonnell Voodoo Jet on display here, which was our primary fighter jet from 1961 to 1984.

There is no parking lot per se at Fort Levis No. 1, you just park on the street that fronts it, which attests to how few visitors this place gets. Hopefully this post might help change that.

The area encompassed by the fort is surprisingly small and although it looks not that much different from other Canadian forts that are much older National Historic Sites, it actually incorporates engineering features that were state of the art in the 1860’s, starting with the entrance.

This is a unique rolling bridge that acts not that much differently than a draw bridge, except that it is pulled back inside the fort by way of a winch and rails that were turned by hand. It took a full 45 minutes to fully retract so you had to hope you saw the enemy coming well in advance, which was not just wishful thinking. Being on the highest point of ground and with all the trees in the surrounding area cleared, you could see see any potential threat long before they arrived at the fort’s gate.

Inside I am met by Parks Canada manager Jean-Simon Paris who will give me a guided tour. You too can request a guided tour for your visit.

This is a map of Fort Levis No. 1. It almost looks like a house, but looks are deceiving. The roof as it were is much higher than the floor.

We ascend these stairs to the highest point of Fort Levis No. 1 from where you can literally see for miles and miles. Jean-Simon points out the location of the former Forts No. 2 and 3., which were actually built by private contractors as opposed to Fort Levis No. 1 which was built by British military engineers.

The key to defending Fort Levis No. 1 were the 7 inch Armstrong gun artillery pieces that at the time were state of the art breech loaded with rifled barrels and much more accurate than the muzzle loaded cannons in use for centuries. We could have pounded the Americans from two miles away with these weapons.

I have seen Armstrong guns in many places around the world, but have never seen one that still can pivot on its original rail as does this one at Fort Levis No. 1. Jean-Simon tells me that when they get a visit from school kids, they get a chance to collectively push the gun which takes quite an effort, but is rewarded with cheers when it finally moves.

There are a number of older and smaller artillery pieces on display at Fort Levis No. 1 like this cannon forged way back in the reign of George I.

For me, the most interesting and informative part of my visit to Fort Levis No. 1 was the powder magazine. Usually these are boring empty spaces that are dank and dark. Not so here.

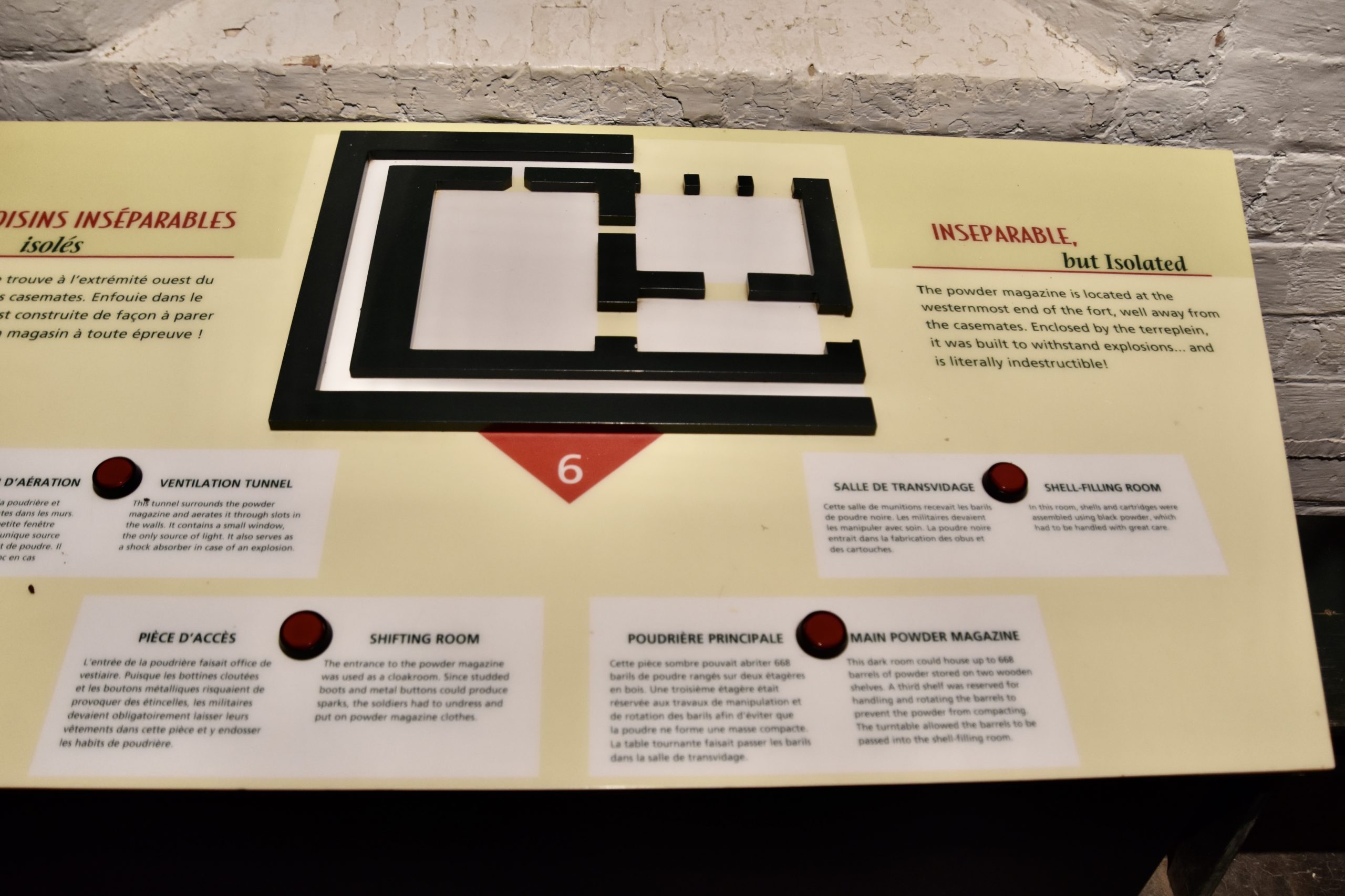

This is a map of the powder magazine and it has a feature I’ve never seen before, it’s completely separated from the rest of the fort by tunnel.

Explosions of powder magazines were responsible for some of the most disastrous incidents in military history. My favourite is explosion of the Fort York magazine on April 27, 1813 which rained down debris on the heads of the seemingly victorious American troops storming the fort killing the American leader Zebulon Pike (of Pike’s Peak fame) and 38 others, wounding another 224, many of whom died from their wounds. It was the ultimate Pyrrhic victory on Canadian soil. To this day, it is not known if the British had deliberately mined the magazine of if it was, for us, just a fortuitous accident.

So making the powder magazine impregnable was of paramount importance and the building of this tunnel was an innovation intended to do that.

I had no idea that the men who worked inside the powder magazine had to change into these linen garments before entering the magazine. Static electricity was always a hazard in powder magazines and linen is a natural anti-static material – who knew?

Here’s another thing I did not know – every single barrel of gunpowder had to be rotated every friggin’ day. Every one knows the expression ‘Keep your powder dry’ and apparently if left just sitting, moisture from the air will seep into gunpowder rendering it useless. The Fort Levis No. 1 powder magazine held 700 barrels of gunpowder and this poor bastard had to move all of them every day.

See the lamp in the photo above? It was actually behind a protective pane of glass with no chance of it causing an explosion, but Jean-Simon did tell me there was a way that enemies could detonate a powder magazine although it would be akin to a suicide bombing. There are a few tiny holes on the magazine walls that allow for air circulation, but they are designed so that no one could stick a hand through. However, if you lit a rat’s tail on fire and dropped it into the slot it would jump down into the magazine and Kaboom!

The things you learn on these Parks Canada guided tours!

Fort Levis No. 1 has four caponiers which are underground constructions with narrow openings that allow snipers to fire on attackers that have beached the moat that surrounds the fort. Our national anthem contains the line ‘We stand on guard for thee’. Well this fort has this ever vigilant soldier who has been doing just that for the last 150 years or so.

More serious for attackers was the presence of small cannons in the caponiers that could fire any number of things at them from point blank range including grapeshot, chain and canister shells.

During school visits this cannon is used to teach students how to load, fire and reload in a timed exercise to see how they would stack up against a properly trained crew. It’s fun, but they don’t.

Fort Levis No. 1 had 12 casements or in simpler terms, rooms underneath the terreplein where the soldiers on duty were quartered. Today these casements have a number of exhibits plus the administration rooms.

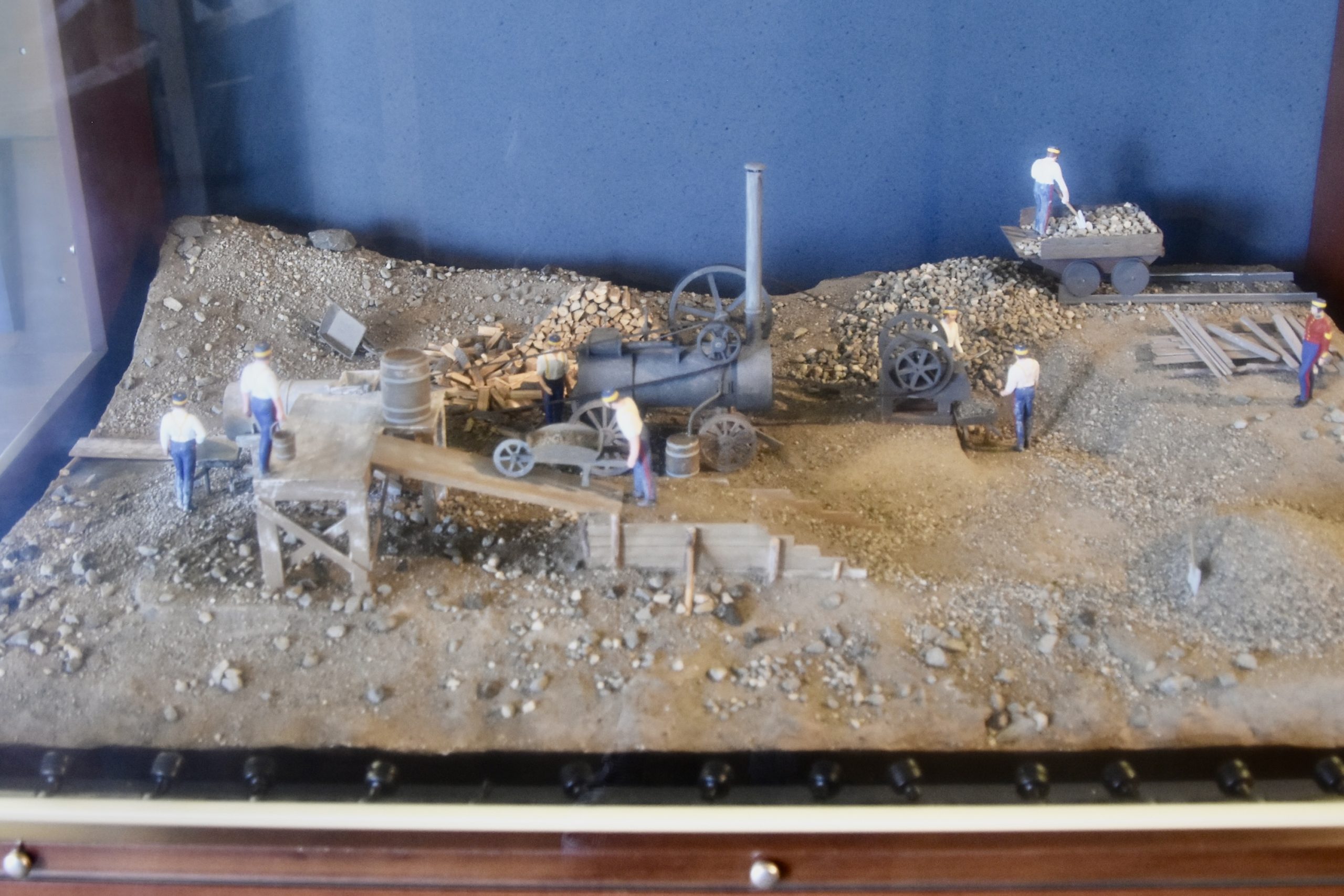

One of the innovations first used at Fort Levis No. 1 was the development of Gavreau or black cement using stone from Cape Diamond. It was designed to be more resistant to the wet and freezing conditions of a Canadian winter than the more traditional Portland cement. This diorama shows workers making black cement using a steam engine to power a rock crusher.

Also found in the casements is this recreation of the Officer’s Lounge complete with Queen Victoria overlooking the proceedings.

My last stop at Fort Levis No. 1 was a familiar one – the red chairs.

In these turbulent times a visit to Fort Levis No. 1 will hopefully reassure Canadians that we have gone through this before and come out unscathed and we’ll do it again.

In my final post in this series I’ll visit Les Forges du Saint Maurice where North America’s iron and steel industry was born. I hope you’ll join me.