Cordoba – A Tour of Spain’s Moorish Capital

It’s a beautiful morning in Cordoba, Spain and after a great night’s sleep at the fabulous Balcon de Cordoba hotel Alison and I are about to explore some of the famous landmarks of the city including the Alcazar, the Calahorra Tower and the Roman Bridge. We’ll save the Mezquita or Grand Mosque for it’s own post. Won’t you come along for what promises to be a very enjoyable morning? But first, a little about the history of this ancient city and its role as the centre of the Moorish culture in Spain.

History of Cordoba

This page at Spain Then and Now gives a fairly detailed overview of the history of Cordoba, but if you are short on time or attention span here is a Cole’s Notes version. While Cordoba is usually most closely associated with the Moors, it was actually founded by the Carthaginians who gave it the name Kartuba from which the present day name is a corruption. The location of the city was chosen because it is the highest point of navigation on the Guadalquivir River and provided a method for transporting goods and people back and forth from the Mediterranean. The Romans conquered the city in 206 B.C. and occupied it for hundreds of years during which time it became the foremost city in Spain. They also built the Puente Romano which still stands today. Under the Romans, Cordoba flourished as a centre of arts and literature producing such greats as rhetorician Seneca the Elder, philosopher and tutor of Nero, Seneca the Younger and the poet Lucan.

Not long after the fall of the Roman Empire, the Visigoths arrived and they in turn were conquered by the Moors in 711 who remained until 1236. It was under Moorish rule that Cordoba was revived as a centre of learning including both arts and science. It became a caliphate, which essentially meant that its leaders or caliphs were considered direct descendant’s of Mohammed and thus their pronouncements on religion were infallible. By the year 1,000 Cordoba was the biggest city in Europe with a population guestimated to be anywhere from 300,00 to a million – somewhere in between is most likely. Regardless of which figure is correct, it was an enormous city by medieval standards and it was this Cordoba that many historians identify as a place of harmony where Muslims, Jews and Christians lived in peace together. Others believe that this is a distorted view and that the Jews and Christians were always discriminated against.

In any event, it was squabbling between rival Moorish factions that led to the initial decline of Cordoba when it was sacked and changed hands many times before it fell to King Ferdinand III of Castille in 1236. It has remained in Spanish hands ever since, but lost its place of importance to the point that by the 1700’s it had only 20,000 residents.

Recently the city has been revived once again and now is home to over 325,000 people. In 1984, the historic centre of Cordoba was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site which has given it a considerable tourism bump. It is parts of the historic centre that we will visit this morning.

Walking the Historic Centre

Here is a map of the walk which is essentially down to the Guadalquivir River, right turn to the Alcazar, over the bridge and down the other side to the Calahorra Tower and the Puente Romano and back into the old city.

The starting point is our hotel, the wonderful Balcon de Cordoba which I described in this post. Right next door to the hotel is one of the many leather shops for which Cordoba has been famous. Cordovan leather, as it’s usually called, is made from horse hides that are tanned in vegetable oil in a process dating back to Moorish times. It’s great for making durable shoes, but quite pricey. I’m happy with my Naot sandals, so we just window shop.

At the end of the narrow street that the hotel is on we come to a massive wall that is the side of the Mezquita or Great Mosque. We’ll be coming back to visit the interior in the next post, but this is the exterior of the Mihrab, which is the point closest to Mecca and identifies the direction for the faithful to make their prayers.

Just down from the Mezquita this young white-robed monk was proof that religion still plays an important role in the lives of some Cordobans.

Signs of Moorish architecture abound in this part of the old city.

The Alcazar of Cordoba

A few more steps and we are at the first and most important stop of the walking tour, the Alcazar. Alcazar is an arabic word for fortress and one would naturally think that this Alcazar was built by the Moors, like the others in Spain. That would be wrong. This is the Alcazar de los Reyes Cristianos (Alcazar of the Christian Monarchs) and it was built after the city was retaken from the Moors. It would be over 250 more years after Cordoba fell that the last Moorish stronghold in Spain, Granada was captured in 1492. The need for a strong fortification overlooking the river and protecting the Roman bridge was obvious at the time. The entrance fee is 4.5€ and includes the building and the extensive gardens. Let’s start with the Alcazar proper.

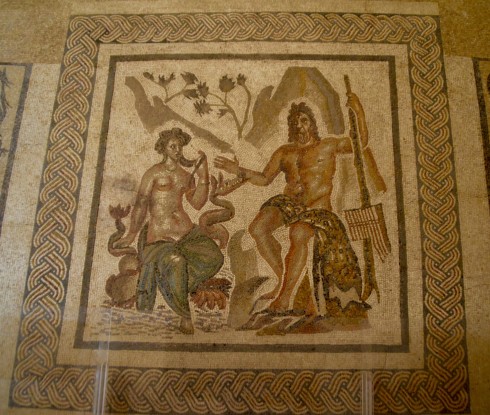

The Alcazar is mostly empty space and pretty gloomy in some places, but there are some really good Roman mosaics including these two. The first illustrates the sea nymph Galatea with the cyclops Polyphemus who allegedly killed her preferred lover Acis. As this Polyphemus can apparently see, this depicts a scene before Ulysses blinded Polyphemus in order for his men to escape from his cave. The website describes the scene further and declares this to be one of the most important Roman mosaics in existence and I have to say it is as good as any I’ve seen in my travels. It’s behind plexiglass so the photo does not do justice to the exquisite colours of this work of art.

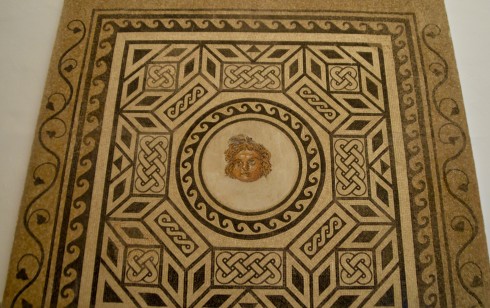

The second is a rather cherubic depiction of the gorgon, Medusa whose gaze would turn any who looked upon her to stone. I guess that’s why she’s not looking directly at the viewer. Wouldn’t want to get stoned, would we?

Also near the Hall of Mosaics is a bust of Seneca the Younger with whom I posed for this photo. The poor bastard taught Nero everything he needed to know, except how to be grateful. Nero forced him to commit suicide after being implicated, perhaps falsely, in a plot to assassinate the deranged emperor.

Aside from the Roman artifacts the most interesting thing about the Alcazar of Cordoba is the view from the top. You get a great look at the Roman bridge and if you look closely, the Moorish waterwheel.

The gardens of the Alcazar are definitely worth visiting. They are formal and contain some really nice sightlines like this one.

Alcazar Gardens, Cordoba

And some other nice sights as well.

Also in the gardens is another familiar Andalusian theme, Columbus meeting with Ferdinand and Isabella.

After exiting the gardens we cross over the Guadalquivir River on a modern bridge to reach the other side. Underneath the bridge was a mixture of pasture and scrub brush where herds of goats were wandering freely.

On the other side there are great views of the old city. Don’t ask me why I didn’t take any photographs to prove it. One thing we did see that was disquieting was this. Anti-Semitism is apparently alive and well in modern Cordoba.

Other than this, it was a pleasant walk to the Calahorra Tower which once stood guard at the southern end of the Puente Romano. Today it’s an eye pleasing relic. Originally there were two rectangular towers through which you had to pass to get onto the bridge. Later they were joined together by the circular tower you see in the middle.

The Puente Romano was originally built in the first century A.D., but has been rebuilt many times since. That does not take away from the fact that the original foundations are over two thousand years old. Like all Roman bridges it has an architectural symmetry that is very eye-pleasing. Today it is pedestrian only and there is something special about entering the city the same way that millions before us have done. This is a view from the first bridge.

This is the view from the Puente Romano.

The Puerto del Puente (Bridge Gate) is the final obstacle to gaining entry to the old city. It dates to the time of Phillip II, but there was a gate here as far back as Roman times.

We have now returned to the outside of the Mezquita. Time to get some lunch and then check it out.