Hatshepsut and Her Temple at Luxor

This will be my final post on the fantastic trip Alison and I took to Egypt last February with Canadian tour company Adventures Abroad. You can find another dozen on this website including visits to the Pyramids and the Temple of Karnak. The west bank of the Nile across from the city of Luxor contains perhaps the most important collection of monuments, temples and tombs in all of ancient Egypt. In a previous post I described our first crossing of the Nile to visit the legendary Valley of the Kings and the most famous tomb in history – King Tutankhamun or King Tut. Today we are returning to visit a number of other important west Nile sites including the Temple of Hatshepsut, the Colossi of Memnon, the Valley of the Queens and several others. Won’t you join us?

The Colossi of Memnon

After an early morning crossing of the Nile, we are met by our bus and head for the Valley of the Queens, but there will be several stops along the way. Our first stop is at one of the most famous monuments of ancient Egypt, the Colossi of Memnon. These are two massive solitary statues of Amenhotep III, one of the greatest of all Egyptian kings, father of the heretic Akhenaten and grandfather of Tutankhamun. So why aren’t these statues referred to as the Colossi of Amenhotep? Good question. Memnon is a figure from the Iliad, a legendary Ethiopian king who came to fight with the Trojans and was ultimately slain by the even greater warrior Achilles. Early Greek tourists, and I do mean early, like around the year 300, had no clue about Amenhotep, who by then, had been dead for 1600 years. They did know about Memnon who was from Africa so they attributed the statues to him and the name stuck.

For centuries the statues were also famous because they ‘sang’. Early travellers reported hearing strange whistling noises coming from one of the statues after it was damaged by an earthquake. This lead to the statues becoming a place of pilgrimage until the Roman emperor Septimus Severus thoughtfully had the damaged statue repaired and it never sang again. Ever since I was a boy first reading about ancient Egypt I have wanted to see these statues and here we are.

As you can see they are in a pretty bad state of repair and kind of forlorn out here by themselves. That’s too bad because when they were built they stood at the entrance to a mortuary temple complex larger than Karnak including a huge man made lake. Now it’s pretty well all gone with only the two solitary guardians, sentinels of nothing. While Shelley’s poem Ozymandias was written about a giant fallen statue of Ramses II, which we saw in Memphis, the closing line could equally apply to the Colossi of Memnon – Round the decay of that colossal wreck , boundless and bare the lone and level sands stretch far away.

However, not all of the mortuary complex of Amenhotep III is lost as we discover a few miles down the road. Our Egyptian guide Ahmed Mohsin Hashem is also an Egyptologist who does regular field work in the summers when he is not guiding. He points out a team from an American university that is working at the mortuary complex. This provides valuable employment to Egyptians and a great summer job for budding archaeologists.

The Temple of Madinat Habu

One of the things that Ahmed is very good at is getting our group to places that are off the beaten tourist path, but very much worth seeing. He got us through a military check point at Dahshur and right up to the base of the beautiful Red Pyramid with the Bent Pyramid in the background. This morning he is taking us to the Temple of Madinat Habu which he assures us will be virtually deserted and he’s absolutely correct. This is the mortuary complex of Ramses III another of the great Egyptian kings who successfully staved off three invasion attempts by outsiders during his extensive reign.

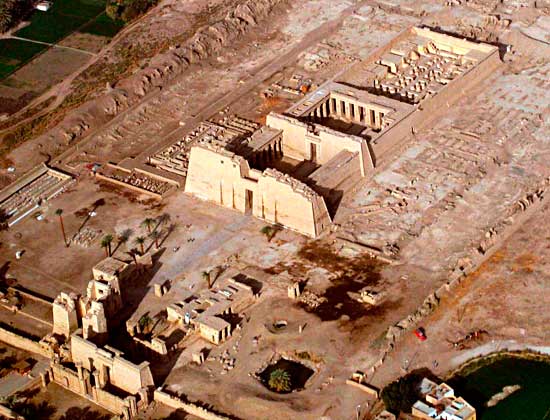

This aerial photograph shows just how extensive and well preserved the complex is. So why don’t most tour groups visit this place? I think the best answer is temple fatigue. The Luxor area has the temples of Karnak, Luxor and Hatshepsut not to mention the Valley of the Kings and Queens. In my experience, travellers with Adventures Abroad are usually quite knowledgable about the destinations they are visiting and have an appetite for visiting the lesser known attractions that is not diminished by long days and less than ideal road and restroom conditions. It also helps to have the enthusiasm and knowledge of Ahmed and our Canadian tour leader Martin Charlton as driving forces.

This the entrance pylon to the temple. Compared to the madness outside the Temple of Edfu this is tranquility.

One of the reasons Ahmed wanted us to visit this complex was because it is so well preserved and that is evident immediately upon passing into the inner courtyard. Note the rarely used square pillars in addition to the usual cylindrical shape.

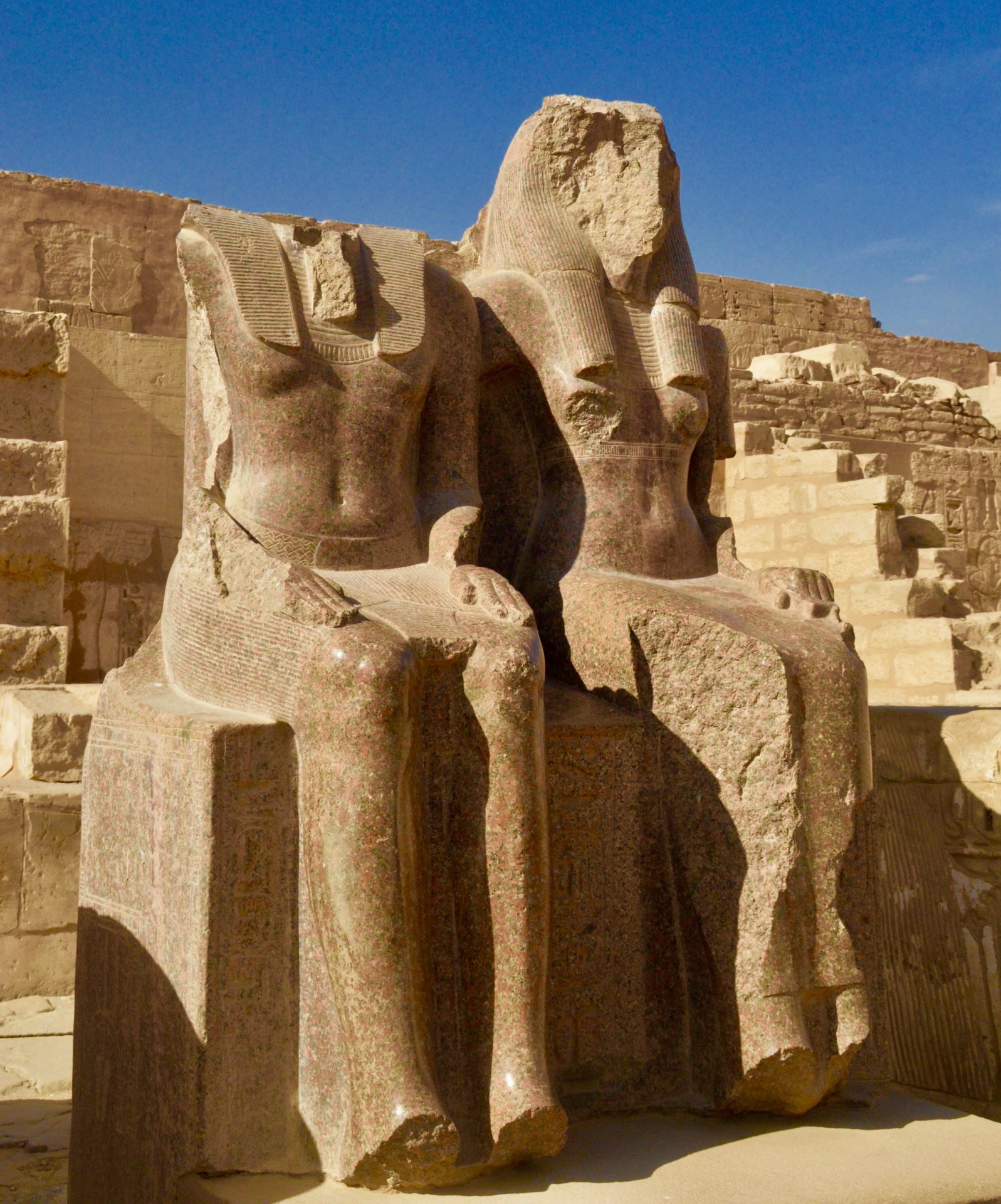

This is Ramses III and one of his wives.

In areas where the light has not shone directly on the walls the painting is still vivid. This is Isis and Thoth.

This is a painted ceiling, still fresh after over 3,000 years.

Ahmed pointed out some features unique to buildings erected by Ramses III. These are deeply incised hieroglyphs that are only found during his reign.

I mentioned that Ramses III was involved in successfully repelling numerous invasions and at Madinat Habu he wanted to make sure everybody knew about it. One of the ways of letting him know just how many of the enemy had been slain was to cut off the hands of the defeated. Here the figure on the right is standing before a stack of severed hands.

Ramses got to thinking about this hands business and realized that he could easily be duped about the numbers of enemies killed if both hands were severed and each pawned off as coming from a separate person. Hmm. What male body part could be cut off instead to avoid any doubt as to the number killed. You guessed it. This is a representation of a man, knife in hand, standing before what would be a huge number of severed penises. Gives me the willies just looking at it.

The Worker’s Village

Our next stop is also not on the usual tourist itinerary and offers a rare look into how the vast majority of ancient Egyptians lived out their lives in complete obscurity compared to the monuments left by the 1% or less. Somebody had to build these monuments and they had to have a place to come from and return to after every day’s labour. This is the Deir-el-Medina or worker’s village that is located about midway between the Madinat Habu and the Temple of Hatshepsut. It is where the artisans who worked on the temples and tombs lived out their lives and miraculously it is reasonably well preserved.

Can you imagine the heat of the summer beating down on this barren and shadeless landscape?

This was the community well from which all who lived here had to draw their water. Not quite as easy as just turning on a tap.

The worker’s village lasted for a period of four hundred years and is unique in Egyptology as the only site of its type ever discovered and like Madinat Habu, it sees few visitors.

On the same site of the worker’s village, but not exactly contemporary with it is the Ptolemaic Temple of Hathor which from the exterior looks kind of ordinary and uninviting. However, it would be a big mistake not to go in because it contains some very rare depictions of ancient Egyptian beliefs.

The idea of judgment after death is an almost universal religious belief and one that the Egyptians held for thousands of years – still do for that matter. This is a scene from the Book of the Dead depicting the final judgment of a dead person’s worthiness to be resurrected to a second life or be eaten by the devourer of the dead Ammit and extinguished from existence for all time. The dead person’s heart is placed on a scale, in this depiction, held up by Horus. On the other side the cat goddess Ma’at places a feather. If the heart outweighed the feather then it was bye bye heart and soul, if not the person was worthy of a second life. Heavy stuff.

Another rare depiction in ancient Egyptian art is this one of the god Min who is usually portrayed with a very obvious boner and a flail – the first male dominatrix? Not surprisingly he was the god of fertility.

Valley of the Queens

Just a half kilometre away from Deir El-Medina in a narrow valley lies the entrance to the Valley of the Queens. Valley of the Queens is a bit of a misnomer, because it is not exclusively women who are buried here, but it does contain the tombs of many of the most famous queens of ancient Egypt. It receives only a fraction of the visits than the much more famous Valley of the Kings which is too bad for those who don’t get here because it has very well preserved tombs including the one that many people think is the finest in Egypt.

Unlike the Valley of the Kings, visitors are allowed to take cameras inside the valley and can take photos of the exterior entrances.

As you can see the place is not exactly overrun with tourists. The square grilled boxes mark the opening to some of the ninety tombs that have been discovered here so far.

Other tombs that are cut directly into the valley walls are sealed off by wooden doors.

Like the Valley of the Kings a few tombs are open to the public each day. On our visit today it is that of Queen Titi (not to be confused with Nefertiti) which is not that inspiring. The other two are both princes and one has this fine painting of two Amuns facing east and west.

However, the real reason to visit the Valley of the Queens in my opinion is to see the recently reopened tomb of Queen Nefertari, favourite wife of Ramses II. Closed for a restoration that took over twelve years, the tomb is considered the ultimately beautiful tomb in Egypt. There is only one catch – it costs $50 USD to see it and you can only stay for ten minutes. Only a few others in our group opted to make this $5 a minute expenditure, but for Alison and I it was a no brainer.

This is the modest looking entrance and I was obliged to leave my camera with Ahmed.

Was it worth it? Every damn cent.

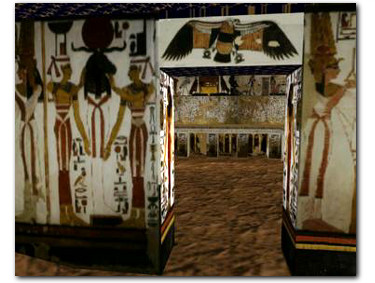

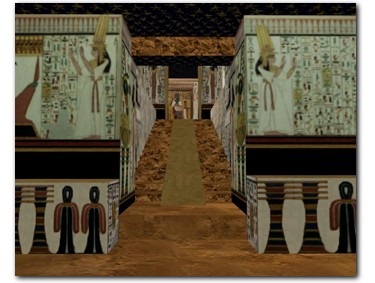

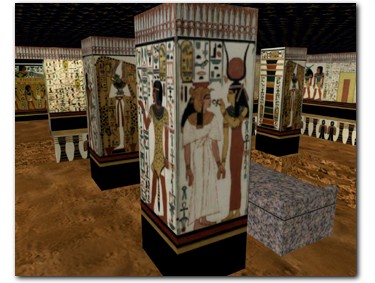

Here are pictures from a CD that Ahmed made available to us for a modest price, compiled by his friend Mohammed Fathy.

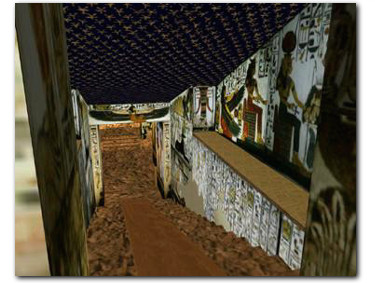

This is the entrance passage and the first thing you notice is that the walls are white. This is a style unique to this tomb and makes the paintings stand out like no other. Also notice the ceiling painted blue with stars.

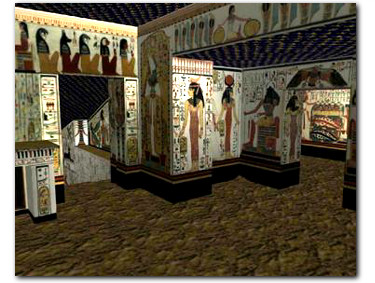

Once you are inside the colour is breathtaking and unlike viewing say the Mona Lisa, you are not jostled or thronged by others. The only limitation is that darn ten minutes and once inside, for a little baksheesh, they would let you stay longer. However, I don’t promote breaking the rules and we dutifully exited on schedule.

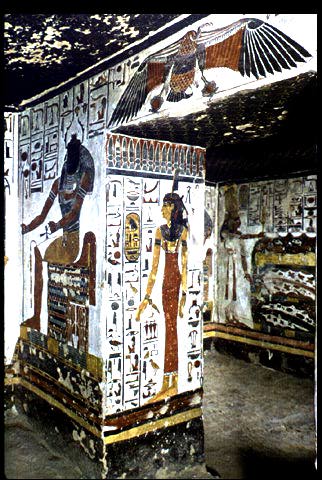

Here is more of what you’ll see on one of the most memorable ten minutes of your life.

There are lots more, but it’s time to visit what might be the most interesting site on the west bank, the Temple of Hatshepsut.

The Temple of Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut is one the most colourful and controversial figures in ancient Egypt. She was the most successful woman to rule as king of Egypt, having transcended from a regent for Thutmose III to in effect a co-ruler until she died. Reigning as a king and depicting herself as a man she constructed one of the most beautiful and famous temples in all of the ancient world. It was constructed as a mortuary where she could be worshipped after her death. Her actual tomb is in the Valley of the Kings. It is also the site of the most infamous terrorist attack on foreign tourists ever.

Ahmed has deliberately delayed our visit to the Temple of Hatshepsut until close to the end of the day to avoid the crowds that inevitably deluge the place. That strategy seems to have worked as the place is relatively quiet although nowhere near as much as most of the other places we’ve visited today.

The construction is a radical departure from the other temples we have visited in Egypt. There are three distinct levels which are reached via a gigantic staircase. From a distance it look like it is built right into the cliff face, but that is an illusion as there is a very large open space between the facade and the cliff. However, the chapels of Hathor and Anubis inside the inner temple do extend into the cliff.

Here’s Alison doing her best Hatshepsut imitation.

The most striking feature of the Temple of Hatshepsut for me was the colonnade of statues on the second level. Note that she is depicted as a man, fake beard and all. Traces of original paint remain on some of them.

The restoration work inside is ongoing under the auspices of the Polish Academy of Sciences and there’s nothing overwhelming about the interior. The Temple of Hatshepsut is really mostly about its grand exterior which really has to be seen to be appreciated. It is truly one of a kind.

The Temple of Hatshepsut Massacre

Looking down from the second level Ahmed points out the area where 70 people were massacred in a terrorist attack on November 18, 1997. One thing I appreciated about Ahmed was that he did not try to downplay or dismiss events that did not put Egypt in the best light. Since the attack security has been tightened to the point that future attacks of this magnitude are highly unlikely, but then again the purveyors of terror always seem to come up with new ways to make life miserable for the rest of us.

I don’t want to end this post on a down note so I will end by pointing out the cliffs which you can see from the temple where the actual mummies of over fifty Egyptian kings, including Ramses II, were discovered in a cave in 1881. They had been secreted from their tombs by priests concerned that they would be desecrated by tomb robbers and remained hidden for another 3,500 years.

We’ve packed an awful lot into this day and as noted this will be my last post on Egypt until I return when the new Egyptian Museum opens in Giza. I hope you have enjoyed them. In the meantime here is a link to the Egypt photo gallery with over one hundred and fifty pictures from this amazing trip.

Ila al-liqaa.