Calais Canadian War Cemetery – A Visit To An Uncle Never Met

In my last post we visited the largest Commonwealth War Cemetery, Tyne Cot and I contemplated the senseless slaughter that took place in the Ypres area over the entirety of WWI. From there we are headed into Holland for events related to its liberation by Canadian troops in 1944-45, however, Alison and I are taking a detour to Calais Canadian War Cemetery back in France. Here’s why.

Originally I wasn’t going to do this story because it was not part of the Liberation Tour 2015 itinerary and I thought it might to too personal for Alison, but on reflection I think it needs to be included for a couple of reasons. First, even though it was not on the tour agenda, it was the primary reason for taking the tour. Second, as part of this narrative I have wanted to tell the story of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders or North Novas as they are usually called and the role they played in liberating western Europe in WWII. So we are headed to Calais Canadian War Cemetery to visit the grave of an uncle Alison never met, John Weir.

We first came across them at Juno Beach where they took few casualties on D-Day, but engaged in fierce fighting the three days after. We visited the graves of some of them at Beny-sur-Mer Canadian Cemetery.

At Abbeye D’Ardenne we saw where twenty-seven Canadians, mostly North Novas, were murdered in cold blood on Kurt Meyer’s orders.

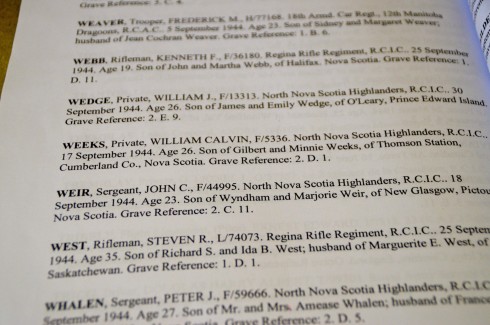

And I know we will see more North Novas in the cemeteries of Holland where we are headed next. All told 475 young Nova Scotians died serving in the North Novas in WWII. One of them was Sergeant John C. Weir who was killed outside of Boulogne, France on September 18, 1944. He was the uncle my wife Alison never met, the oldest son of Wyndam and Marjorie Weir, and an idol to her mother, nine years his younger and the youngest in the family, Mardie. He is buried at Calais Canadian War Cemetery and this afternoon we are going to visit him.

Liberation Tour 2015 has been based in Ypres the past few days and it is about an hour’s drive to the cemetery that is off a small country road outside the little village of Leubringhen, not far from Calais. Fortuitously, the day’s scheduled events have ended earlier than usual and we have a free afternoon to accomplish our mission.

We have hired our bus driver Pieter’s ex-mother-in-law to take us there, whom he assures us, likes him better than her daughter. She can’t speak much English, but arrives on schedule in a bright green Mazda 3, the cemetery entered into her GPS and we are off. We stop only once at a garden outlet to buy flowers. Given how the other Commonwealth war cemeteries we have visited look so good because of the perennials planted at the foot of many graves, we opt for a live plant rather than cut flowers.

The highway is busy, but our driver is quite capable as she navigates the many highways we enter and exit, doesn’t speed inordinately and doesn’t tailgate, so we enjoy the pastoral scenery of the Pas de Calais as it whizzes by. Along the way we pass exits for the historic cities of Dunkerque and Calais before turning off onto secondary roads that take us to a sign for the cemetery.

Calais Canadian War Cemetery

Our driver stops in the small parking lot and Alison and I get out and make our way up a small grassy lane to the cemetery. It is quiet and overcast and I am not sure how this is going to go.

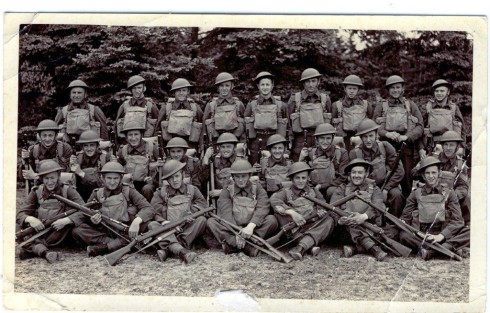

John C. Weir was the oldest of six children born to Wyndam and Marjorie Weir who owned and operated a farm, grist mill and saw mill, in the tiny community of Pine Tree just outside of New Glasgow, Nova Scotia where the Weirs had lived for generations. As the oldest son John would have been expected to take over the farm, but instead the war came along and he enlisted as most others his age did in Nova Scotia. His death led to the farm going to his brother Donald who stayed on it his whole life. Donald’s son John C. Weir lives there today, but the farming stopped with Donald. Here is John after making Sergeant.

Alison grew up in a house located at the base of the the hill, across a field from her grandfather’s house where the farm’s blacksmith shop once stood many years before. Her father built on land given to him by Wyndam Weir, so the farm and the Weir family history were as large as life in her upbringing.

Most of those buried in the Calais cemetery died in the fighting to liberate the key ports of Boulogne and Calais, an assignment that was specifically given to the Third Canadian Infantry Division of which the North Novas were part. John is part of this smiling group of young men, many of whom would never return home including him. He is first on the left in the second row.

There are 674 identified graves and 30 unidentified in this place. It looks quite serene as Alison opens the gate.

In keeping with all of the Commonwealth cemeteries we have visited, Calais has a symmetrical beauty that is both pleasing to the eye and calming at the same time. Most graves have flowers planted at the base.

We search the register and find the exact location of John’s grave. The two entries above and one below are also North Novas.

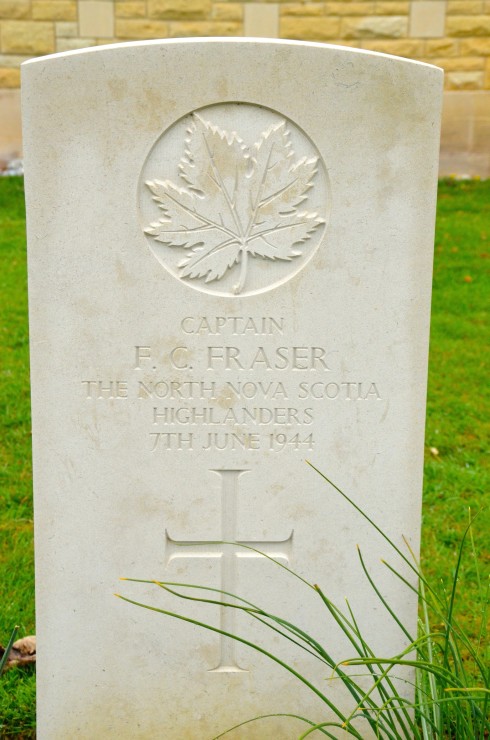

We find John’s grave with no difficulty and it is little different from the hundreds of other around it. The inscription “Greater love hath no man than this. That a man lay down his life for his friends.“, is a common one. It is also one that I can’t take issue with; there is no mention of God, country or family. John died so that those others he fought with, his friends, could hopefully live and return to their country, families and I suppose to their God. The inscription was chosen by John’s father and it really was as simple as that.

I wasn’t sure how Alison would feel emotionally at seeing the grave of a person who had, by the time she was born, lived in her household only as the memory of her mother, her aunts and uncle. John was part of many stories her mother told about her own growing up…the older brother who feared nothing, a natural leader, an accomplished athlete, the apple of his mother’s eye, who idolized the cowboys in movies when a boy, teaching himself to do running mounts onto a bareback mare, who never failed to bring her a chocolate bar after his Saturday night “in town,” and who entertained her with feats of agility on the roof outside her bedroom window when she was quarantined with scarlet fever. The photos of John as young soldier would never be replaced with pictures of his wedding, his children or his grandchildren. If he had survived, we probably would have attended his funeral a few years back, but none of that happened and he lies here today thousands of miles from the farm and family in Pine Tree.

Alison is surprisingly calm and plants the flower we have brought beside the dianthus that is already there. She said she was glad to see John is buried among other North Novas, taking comfort in his final resting place being amongst his comrades, if not his kin in the family graveyard in Woodburn.

I decide to give her some time to reflect and walk the multiple rows to see who else is buried here and as usual, there are any number of interesting stories.

Here are three Canadians and two Englishmen buried together. All died on September 26, 1944 and they are most of the crew of a Lancaster bomber shot down by anti-aircraft fire in a daylight mission over Cap Griz Nez. Two crew members survived the crash landing and those who didn’t now share eternity as friends and crew mates here in Calais Canadian War Cemetery. The grave markers indicate that two of them were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and I can’t help but wonder where those medals are today – hopefully treasured by their surviving relatives or maybe in a military museum such as that run by John Cannon and Phil Craig, the leaders of Liberation Tour 2015. I just hope they aren’t languishing in some pawn shop or lying forgotten in someone’s closet. The deeds of these men deserve to be remembered.

Moving on I find, what for me at least, is a first. The gravesite of of a woman, Margaret Campbell, Leading Aircraftwoman, daughter of Mrs. C.A.Campbell of the Isle of North Uist, Scotland. From what I can gather from the internet this would essentially have been the position of a junior aircraft mechanic. I can find no information as to how she died, but have to presume that for one reason or another she must have been on one of the bombers shot down over this area in the fall of 1944.

It’s good to see from the recent crosses that Margaret has not been forgotten.

Also of note in Calais Canadian War Cemetery are the graves of other nationals who we often forget also participated in the liberation of France. This is Flight Lieutenant Jaroslav Kulhanek who served as a volunteer in the Royal Air Force and hailed from Czechoslovakia.

And then there were those who, although not from Canada, opted to serve with the RCAF. Here is Pilot Officer Frank Chace Downing of Stockbridge, Massachusetts. He was the son of Dr. Franklin and Elsie Downing and husband of Virginia Lomas Downing. He died on June 18, 1942, well before most of the others interred here. My bet is that he joined the RCAF well before the Americans entered the war in late 1941.

And finally, another North Nova; Gordon Dunlap Campbell, son of Everett and Adelaide Campbell of Stewiacke, Nova Scotia. His grave marker also contains the notation that he had earned a B.Sc. which I learn from the on line record, was from McGill. The fact that this was notated on his headstone tells me that his parents were incredibly proud of that accomplishment, one that he would never get to use.

The inscription on his grave is from Robert Browning’s Epilogue and is a fitting way to end my tour of the dead men and women buried at Calais Canadian War Cemetery

I return to take Alison’s arm and we slowly walk back to the car. On the return trip to Ypres I stare out the window at the passing fields without really seeing and contemplate the terrible loss that John’s death was to his family and the consequences that flowed from it. His own mother would never recover from her grief. She died little more than a year later, at the early age of 56. The family believes it was of a broken heart. And then I think of the losses of the families of the hundreds of others buried at Calais. And then I extrapolate that to those buried in the hundreds of other war cemeteries and soon, like trying to comprehend the dimensions of the universe, I just can’t fathom it anymore.

Rest in peace, John. Your friends and family have not forgotten you.

Things get a lot less morose for the rest of Liberation Tour 2015 as we head for Holland and the 70th anniversary celebrations at Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery. Please join us.