Ortona – Our Canadian Version of Stalingrad

This is the tenth post on this fall’s tour of Canadian WWII battle sites in Italy, sponsored by Liberation Tours. In the previous post I described the horrific fighting that took place to cross the Moro River and The Gully, just south of the seaside town of Ortona. With the southern and western roads into Ortona secured, the Canadian forces expected that perhaps the Germans would evacuate the town and withdraw to their next line of defence, the Arielli River. They didn’t. Instead they dug in and fought one of the most ferocious battles in Canadian military history. For those who fought for eight days over the Christmas season in 1943, Ortona was forever known as the Stalingrad of Italy. Won’t you join us to find out more about this important Canadian military victory?

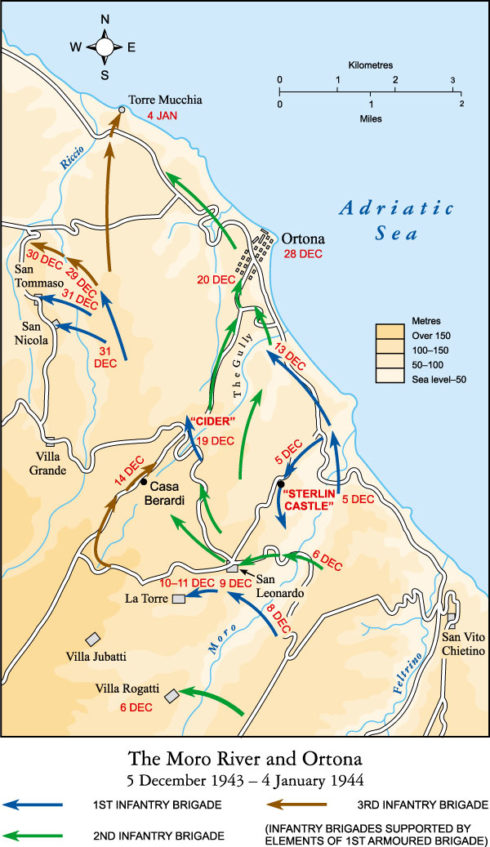

The map above shows the progress that Canadians forces made in the month of December under the command of Major-General Chris Vokes He’s not one of my favourite characters given his disregard of the lives of his men in ordering eight doomed frontal assaults on dug in German positions at The Gully. However, he was under constant pressure from Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery, head of the 8th Army of which the Canadians were part, to make faster progress up the Adriatic coast. Vokes’ toadyism led him to demand and sometimes get results from Canadian soldiers that, in retrospect, seem almost impossible.

Ortona – The Pearl of the Adriatic Loses Its Lustre

Ortona has a history that goes back to the Bronze Age and has been governed over the years by the Romans, Byzantines, Lombards, Franks, the Kingdom of Sicily and the Duchess of Parma before being incorporated into the Kingdom of Italy in 1860. Ortona’s fame as the Pearl of the Adriatic comes from the late 19th century when the railway made it an easily accessible seaside resort for wealthy and middle class Italians seeking relief from the oppressive summer heat. Not a beach resort in the traditional sense in that it sits on a clifftop some 100 feet or so above the Adriatic, Ortona’s place in the sun was relatively fleeting. By the time WWII came along it had a genteel shabbiness that attracted fewer and fewer tourists. In the course of a week in December, 1943 any semblance of the Pearl of the Adriatic was forever destroyed, which raises the question, “Why did the Germans fight so hard to defend what was a not a particularly strategic or important city?”

The Italian Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad was the single largest German defeat in WWII with the loss of the entire 6th Army. Blame for the staggering loss of men and materiel lies directly with Adolph Hitler who refused to let his troops retreat or attempt to break out once they were encircled by Russian forces. Comparing Ortona to Stalingrad is obviously a stretch (it is estimated that there were upwards of 2,000,000 casualties on both sides at Stalingrad), but there are some valid comparisons. First, like Stalingrad, the Germans could probably have extricated themselves from disaster, if they had been allowed to retreat. The road north was still open to them when the Canadian advance on Ortona began. Second, like Stalingrad, Hitler personally gave orders for Ortona to be held at any cost. Why didn’t seem to matter – he was very adept at squandering some of his best commanders and troops on impossible to succeed orders.

From the beginning of the Italian Campaign in June, 1943 and up until mid-December, the 8th Army had been facing off primarily against Panzergrenadiers who were certainly capable, but would not be considered an elite fighting unit. That distinction would certainly apply to the 1st Parachute Division which was comprised entirely of volunteers, most of whom had been in service prior to the war. These were highly trained veterans who had fought in Denmark, Norway, Russia and the Caucusus. I first learned of these fierce bastards years ago on Crete where I visited the graves of hundreds of Commonwealth soldiers killed by them during the German invasion of that island. In December, 1943 they were ordered to take over the defence of Ortona. Their reputation was that they simply did not surrender and would always fight to the death. They were the perfect tool for Hitler’s order to defend Ortona at all costs.

I could spend a lot of words describing the Battle of Ortona, but I think the reader will get a better appreciation by watching this 15 minute video that summarizes things quite well. Although the video shows as being 47 minutes long, the portion on Ortona is the first 15 minutes. Afterwards I’ll describe our visit to Ortona almost 75 years after the battle and then we’ll make a final stop at the Moro River Canadian War Cemetery.

Liberation Tours in Ortona

We arrived in Ortona in the early afternoon after spending the morning touring sites around the Moro River which I described in the last post. Our first stop was the Miramar restaurant which, consistent with its name, had a great view of the Adriatic and equally good food – pasta fagioli followed by sliced lamb. Phil Craig, lead historian and raconteur extraordinaire provided us with more details of the troubled after war life of Victoria Cross winner Paul Triquet. We had just visited Casa Berardi where Lt. Triquet earned his VC shortly before the Battle of Ortona was to begin.

After lunch Alison and I took a brief stroll along the Ortona miramar which overlooks the port below. The city has transitioned from tourist destination to industrial port.

This is Ortona today.

My sister Anne then took this picture to prove we were in the Stalingrad of Italy.

The group then met on the main street of Ortona, Corso Vittorio Emmanuele, which was where much of the fiercest fighting occurred. The map shows the progress of the two Canadian regiments that did most of the fighting, The Loyal Edmonton Regiment (Loyal Eddies) in blue and The Seaforth Highlanders (Seaforths) in red.

This is what Corso Vittorio Emmanuele looks like today.

This is what it looked like on December 23, 1943 as the Loyal Eddies supported by the Three Rivers Tank Regiment reached it after three days of fighting their way up the Ortona-Orsogna Lateral into Piazza Vittoria

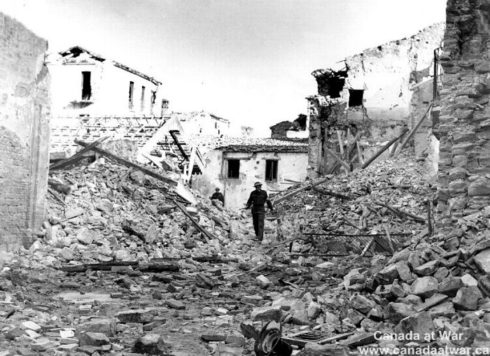

This is what Ortona looked like after the battle.

Ortona has created a walking tour of the most important sites of the battle which makes it very helpful in exploring the sometimes confusing maze of streets and side streets. It also helps to have Mark Zuehlke, the guy who literally wrote the book, in fact two of them, on the Battle of Ortona, along as our official historian. Mark spent a lot of time in the city researching his books Ortona:Canada’s Epic WWII Battle and Ortona Streetfight and this afternoon he’s back to lead us around.

We start on Corso Vittorio Emmanuele with an explanation of the warfare technique of ‘mouse holing’ whereby Canadians would go from house to house by blowing down the walls of adjoining structures and clearing out the defenders.

Mouse holing was safer than risking going door to door as these were often booby trapped and the men would be exposed to sniper fire, However, the Germans cottoned on to what the Canadians were doing and on December 26 an entire platoon of 24 men was wiped out, but for one man, when a building they were occupying was blown up. The Canadians retaliated by killing up to 50 German soldiers holed up in another building. This was the kind of tit for tat ferocity that marked the fight for Ortona.

Next we made our way into Piazza San Francesco, aka Dead Horse Square by the Canadians, which was liberated by the Seaforths on Christmas Eve.

The Germans had removed the clock face from the church tower and were using it as a gun emplacement which had to be dislodged. This is what Dead Horse Square looked like after it was taken, although this is from a different angle.

Our next stop was at the entrance to the Basilica of St. Thomas the Apostle, the guy who is known as Doubting Thomas in the New Testament. Apparently some huckster in the 1200’s convinced the people of Ortona that he had recovered the remains of St. Thomas who supposedly died in India. We didn’t go inside, but here’s what it looks like from the outside.

And here’s what it looked like after the Germans blew up the bell tower and collapsed it into the dome. It really is impossible to imagine these type of scenes when you are standing in front of the restored exterior. Thank goodness we have pictures, because without them, I think we would all be doubting Thomases about the extent of destruction that befell Ortona.

Canadian war artist Charles Comfort captured the hell that was Ortona very well in this painting simply titled Canadian Armour Passing Through Ortona.

Our last stop on this walking tour of Ortona battle sites is appropriately at this monument showing a Canadian soldier helping a fallen comrade. Once again it’s good to know that our forefathers sacrifice has not been forgotten.

The group is usually pretty solemn after these type of visits, but the tour leaders provide a moment of levity as they struggle to determine just how to get back to our bus.

Moro River Canadian War Cemetery

Moro River Canadian War Cemetery was our final stop on a very busy day in the Ortona area. It contains the graves of 1562 identified remains, almost all Canadian and almost all killed in the battles to take and secure Ortona. As with all Commonwealth Graves Commission cemeteries I have visited, it is well maintained and a place for quiet reflection.

As you can see, the shadows were getting long and we didn’t get to visit a lot of graves, but here are a few that did stick out. This is Ann Smith with Mark Zuehlke at the grave of Major Alexander Railton Campbell, son of Harry and Sarah Campbell of Perth, Ontario. Ann’s father was a member of the Hasty Pees (Hastings & Prince Edward Regiment) as was Major Campbell who wrote an article The Hasty Pees in Sicily describing the regiment’s accomplishments on that island. It has some very interesting photographs attached.

Major Campbell also wrote this very moving poem that describes what I can only imagine to be the weight of leading men into mortal combat without showing the fear that was gripping him inside.

Prayer before Battle

By Major Alex Campbell

When ‘neath the rumble of the guns,

I lead my men against the Huns,

‘Tis then I feel so all alone and weak and scared,

And oft I wonder how I dared,

Accept the task of leading men.

I wonder, worry, fret, and then I pray,

Oh God! Who promised oft

To humble men a listening ear,

Now in my spirit’s troubled state,

Draw near, dear God, draw near, draw near.

Make me more willing to obey,

Help me to merit my command,

And if this be my fatal day,

Reach out, Oh God, Thy Guiding Hand,

And lead me down that deep, dark vale.

These men of mine must never know

How much afraid I really am,

Help me to lead them in the fight

So they will say, “He was a man”.

You can see from his photograph that Major Campbell was truly a man. He was killed in action on Christmas Day in Ortona.

Major Campbell was not the only Canadian killed in Ortona on Christmas Day. This is is the grave of Private Francis Arpentigney, son of Peter and Marie Arpentigney of Belle River, Ontario.

Private Arpentigney was a member of the Royal Canadian Regiment and according to the records I found on line, he died along with two friends, Private Edward Joseph Gozdz and Private Clarence Eckert Kalbfleisch on that supposed day of peace.

Private Kalbfleisch was survived by his wife Alice and an infant son, George Emerson, whom he had never seen.

Here is the grave of Lt. Mitchell Sterlin whose exploits at Sterlin Castle I described in the last post. His parents are listed as Leon and Helen Sterlin of Los Angeles. He was one of the very last to be killed at The Gully, by a sniper’s bullet in the final folly of Chris Vokes – Orange Blossom. In Mark’s book, Ortona: Canada’s Epic WWII Battle he describes the disbelief of his fellow soldiers at Mitch Sterlin’s death. After visiting Sterlin Castle and knowing what he had survived there, somehow it just doesn’t seem fair or right that he lies here before me today, cut down only a few days later.

This is Private Gordon E. Ott, son of Albert and Agnes Ott of Brantford, Ontario. He was only 16 f***ing years old! The Hasty Pees had been in Italy since the beginning. How old could this kid have been when he enlisted? According to Regimental Records, 13 Hasty Pees died on January 30, 1944 which goes to show that even after Ortona fell there was still a lot of serious fighting in the area north of Ortona.

After viewing the graves of Sterlin and Ott, I needed to calm down so I used the little time left to look up some of the West Novas who are buried at Moro River. This is Private Russell Alexandra Cantwell, son of Frank and Theresa Cantwell of Little Bras d’Or, Nova Scotia, one of forty-one West Novas who died trying to take The Gully.

This is Private Hector Chester Rhodenizer, son of Harris and Josie Rhodenizer of Italy Cross, Nova Scotia and husband of Marie. The Rhodenizer’s and many other members of the West Novas trace their ancestry back to German roots that began with the founding of Lunenburg in 1753. He was one of six West Novas killed on January 6, 1944.

The last grave I can bear to describe is that of Captain Everett Mansfield Crouse (also a German name), son of Wynn and Pearl Crouse of Branch LaHave and husband of Helen Isobel Crouse of Belfast, Northern Ireland. Captain Crouse’ narrative is one that many Canadians followed in both world wars, including my maternal grandfather. A member of the militia before the war began he was shipped to England in December, 1939 and shortly after married Helen Isobel Finlay, a member of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (W.A.A.F) from Belfast. They apparently had a happy marriage for almost three years before he was sent to Italy in June, 1943 and where he was killed at San Nicola on February 26, 1944. Helen remarried and had several children, who after her death, sent Captain Crouse’ medals back to Nova Scotia.

I suppose that’s as close as we’ll get to a happy ending in this place as Alison places the last of our four flags at the side of Captain Crouse. However, one last gravesite; that of Sergeant Jean Paul Lemay, one of the Van Doos and son of Henri and Marie Lemay of the small town of Grenville, Quebec. He survived the carnage the Van Doos underwent at Casa Berardi only to die on the first day of the battle for Ortona.

When I first posted this story I did not include Sergeant Lemay, but then I found out he was a relative of my former colleague and current friend Tim Lemay who works for the U.N. in Vienna. I suspect that there are many more close connections that we are all unaware of, to these men buried here and elsewhere in Italy. Thanks Tim for letting me know.

OK, so we’ve broken the Adriatic side of the Gustav Line, but unfortunately our American and British compatriots on the other side are having a tougher time at Cassino. Time for us to give them a hand in the Liri valley. Won’t you join us in the next post?