Kootenay National Park – The Burgess Shale

This is the final post of four on a recent RV trip to four fabulous national parks in the fall. The first three were on Mount Revelstoke, Glacier and Yoho and frankly each one has surpassed its predecessor. However, that’s somewhat akin to claiming that Gretzky was better than Orr or Howe when in fact, they were all great. Kootenay is the only one of the parks I’ve never visited before and I have to say there’s a building sense of excitement as I drive my 29′ Class C RV from Yoho, briefly across the border into Alberta at Lake Louise and then back into B.C. where the park begins. The border between the provinces and between Banff and Kootenay National Parks also happens to be the Continental Divide. Won’t you join me to explore yet another Canadian wonder?

History of Kootenay National Park

Kootenay is a relative newcomer to the Rocky Mountain park system and came into existence in 1920 as part of a deal between the feds and Alberta and British Columbia to build a new road connecting the two provinces. The road, now Highway 93, followed the course of the Vermillion River to its confluence with the Kootenay River and then down the Rocky Mountain trench to the spa resort of Radium Hot Springs. Part of the deal was that five miles on either side of the new road would be ceded to the Federal government and designated as a national park and thus all Canadians and any earthlings for that matter, may enjoy this exceptional landscape.

In 1984 Kootenay along with Banff, Jasper, Yoho and several adjoining provincial parks was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site with this Statement of Significance

Renowned for their scenic splendor, the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks are comprised of Banff, Jasper, Kootenay and Yoho national parks and Mount Robson, Mount Assiniboine and Hamber provincial parks. Together, they exemplify the outstanding physical features of the Rocky Mountain Biogeographical Province. Classic illustrations of glacial geological processes — including icefields, remnant valley glaciers, canyons and exceptional examples of erosion and deposition — are found throughout the area. The Burgess Shale Cambrian and nearby Precambrian sites contain important information about the earth’s evolution.

I am on this trip with my oldest son Alex and his oldest son A.J. who is ten. The one thing we have been looking forward to in visiting Kootenay National Park is a guided hike to the world famous Burgess Shale. I have made reservations to be on the final hike of the season which will depart at 8:00 the next morning from the Stanley Glacier trailhead. I have also made reservations to stay at the Redstreak campground in Radium Hot Springs as it is the only one in the park suitable for RVs. Almost immediately upon entering the park I realize I’ve screwed up – badly.

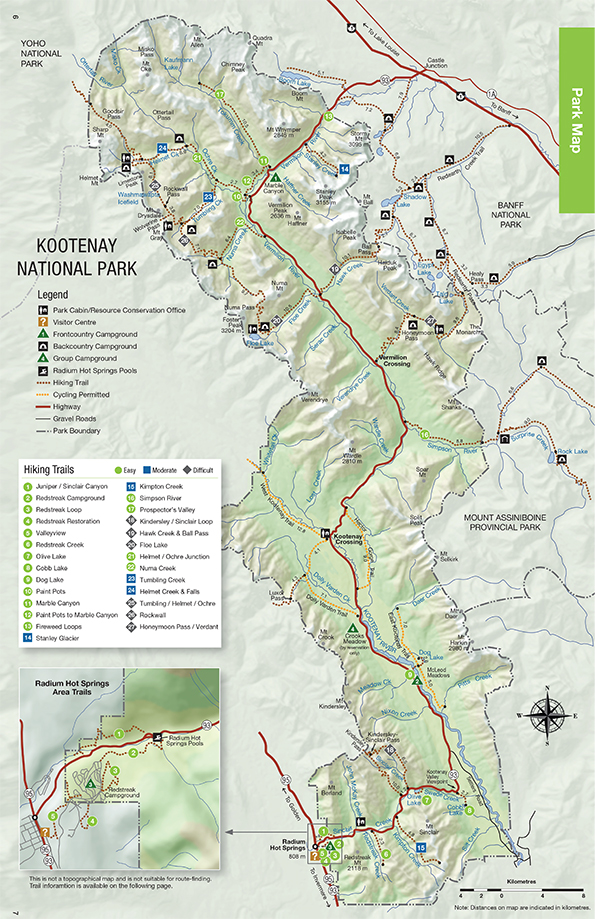

If you look at the map you can see the Stanley Glacier trail as #14 near the top of the map. At the very bottom of the map, over sixty miles (about 90 kms.) away is Radium Hot Springs. There is no way I want to get up really early and drive all the way back here in the dark to make what promises to be an all day hike. I pull into Marble Canyon parking lot and Alex and I discuss our options which include simply staying in the parking lot, which is technically illegal. A few miles back we noticed a sign for Storm Mountain Lodge and I dispatch Alex and A.J. to check it out in the rental SUV we have been using as a backup to the RV.

If I had known how long they would be gone I would have taken the hike up Marble Canyon which is only 30 minutes, but instead I settle for this view. Note the burned remnants of spruce trees. In 2003 lightning strikes started five separate fires that merged into one of the largest in Canadian history. Almost the entire park was engulfed in flames and you can see see evidence not only of the destruction, but of the rejuvenation as well. After the fires were contained the people in charge did an evaluation of what had happened and why. They concluded it was an entirely natural event and that fighting fires merely for the sake of putting them out was not the way to go. Now, unless lives are endangered, the fires are controlled if possible, but not necessarily attacked with every possible means available; that, they concluded, was simply a waste of money.

After what seemed like hours, but was only about 45 minutes, Alex and A.J. returned with news that the Storm Mountain Lodge was booked, but that they had helped him secure the last cottage at Kootenay Park Lodge which was twenty miles from Stanley Glacier trailhead. That was a lot better than sixty miles so, quite relieved, we headed down to the lodge.

Kootenay Park Lodge

Once the road from Banff to Windermere, B.C. was completed in 1920 it opened up the park to motorized tourism and despite being a railway, the C.P.R. seized the opportunity and built a number of wilderness lodges, including Kootenay Park Lodge which opened in 1923. For some reason I didn’t take any pictures, but have cribbed some from the lodge’s website which I’m sure they won’t mind.

This is the original lodge which today doubles as a store and coffee shop.

While most of the cabins which make up the bulk of the accommodations at the lodge date from almost 100 years ago, there was one new one that had two bedrooms and a roll away cot for A.J.

The dining room at Kootenay Park Lodge is everything you would expect in a wilderness lodge – made of logs with a large stone fireplace and the de rigeur stuffed animal heads, antlers, pelts and other symbols of the Canadian mountain experience. Despite being miles from anywhere the food was fresh, properly prepared and great tasting, as was the beer and wine.

While checking in, A.J. found a cribbage board in the shape of an RV which I had to buy and after dinner we had our own mini crib tournament before turning in. We were all looking forward to our final hike together to the Burgess Shale.

The Hike to the Burgess Shale

Ever since I was about six years old I was fascinated with fossils. My father is a geologist and his very first job after graduating from Acadia U. was with the Geological Survey of Canada, the oldest scientific agency in Canada. He was assigned to map sections of the Bay of Fundy coastline that included the famous fossil beds of Joggins and Wasserman’s Bluff. I’ll never forget him bringing home a perfectly preserved trilobite which remains a family heirloom to this day. From that moment on was born a burning desire to become a palaeontologist, which was only extinguished by the fact I was terrible at the sciences. Still my love of fossils has remained unabated and today I hope to pass it on to my grandson as well.

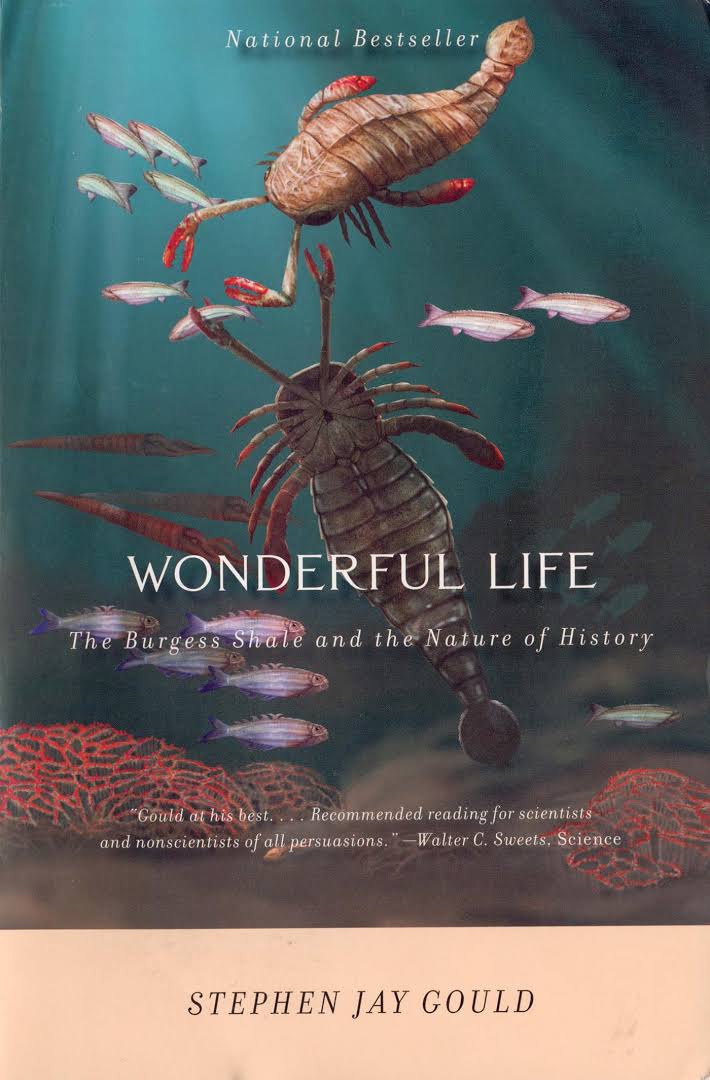

The Burgess Shale was discovered in 1909 by American palaeontologist Charles Walcott on the slopes of Mount Stephen in Yoho National Park at a site now known as Walcott quarry, which we viewed yesterday from the shores of Emerald Lake. The fossils date from over 500 million years ago and are exceptional for their fossilization not only of hard body parts like shell and bone, but soft body parts as well. Dozens, if not hundreds of previously unknown species have been unearthed in the Burgess shale strata. Noted modern American palaeontologist Stephen Jay Gould really brought the Burgess shale fossils to the attention of the everyday public with the publication of Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History in 1989, arguing that they represented the most important fossil find in history.

Even before the designation of the Canadian Rockies as a World Heritage Site, the Burgess shale was put on the list in 1980. So an opportunity to visit to the Burgess shale is something I’ve been looking forward to for years. The question I am sure you are asking is, “Then why are you in Kootenay and not Yoho, where the shale is?” Fair question.

It was not until the 21st century that a second completely separate band of Burgess shale was discovered on the slopes of Mount Stanley in Kootenay National Park. By a touch of serendipity the find was made in close proximity to the already existing Stanley Glacier trail which hikers have been using for decades to reach the ever receding face of Stanley Glacier. Although you don’t need to take a guided tour to hike this trail, your chances of finding fossils and understanding the importance of the Burgess shale will be greatly enhanced if you go with a trained guide.

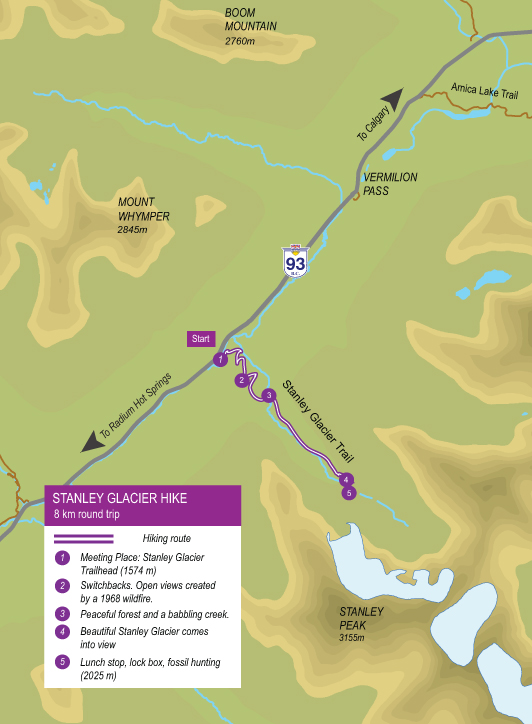

Here is a map of the trail with various stopping points.

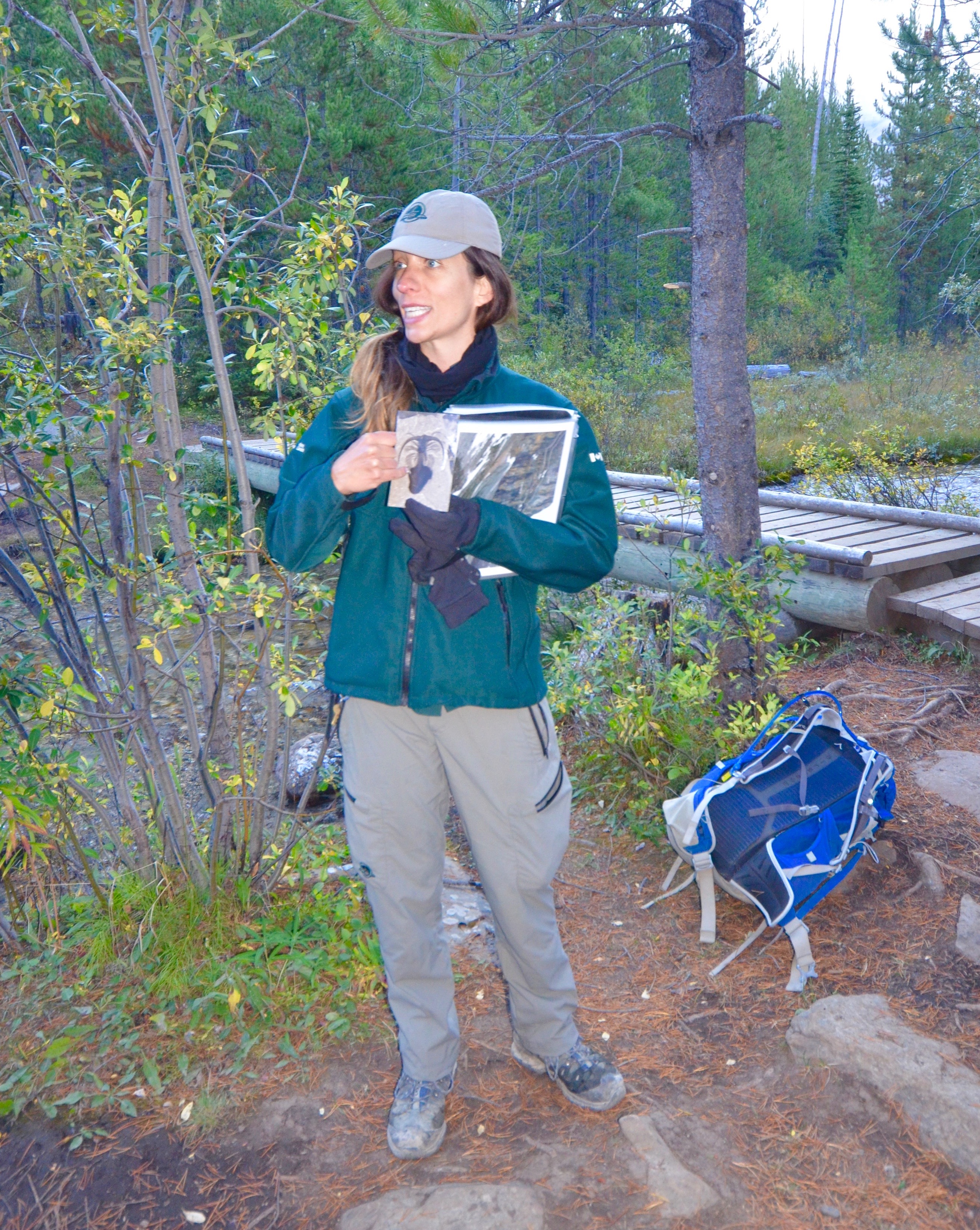

The morning of the hike is sunny and brisk – we can see our breath so gloves and toques are necessary. Later it will warm up considerably so we have several layers each and we each have our own backpack with lots of water, sandwiches and snacks. Surprisingly there is only one other couple signed up for the hike, along with a volunteer assistant who will act as sweeper. Our guide arrives promptly, gets us to sign waivers and asks if anyone needs to borrow walking sticks. We then walk a short way into the trail where our guide introduces herself as Laura Crombeen and I later learn that in a previous life before coming to her senses, she was an accountant in Toronto. Laura gives us a rundown on what to expect on the hike and then a description of the Burgess Shale.

Laura walks at what she calls a ‘guide’s pace’ as we ascend a series of gentle switchbacks that get the heart pumping, but not to the point of needing to stop. Reaching Stanley Creek we get our first view of Mount Stanley. Incidentally the guy this stream, mountain and glacier is named after also has a very famous park and cup named for him, as well.

From this point on the scenery is simply wonderful and I can certainly see why this was a popular trail long before the Burgess shale strata was discovered.

This is Mount Stanley with the band of Burgess shale clearly visible about half way up. The way it works is that each year more and more of the shale is eroded away and falls to the valley floor with the result that each spring after the snow melts there is a whole new batch of fossils just waiting to be discovered.

After a few stops and about three kms. (2 miles) we come to an overlook where Laura goes into a more detailed explanation of how we will descend through a boulder field to a talus slope where we will begin our fossil hunt. Her arms are extended as she explains where the Burgess shale creatures fit in terms of geologic time. One thing is clear by now and that is that Laura not only knows her stuff, but is passionate about it as well. I doubt that anyone could be that passionate about conducting an audit.

The toughest part of the hike is through the boulder field and I’m really glad to see that A.J. is keeping up and keeping interested. This is just before the ascent through the boulder field.

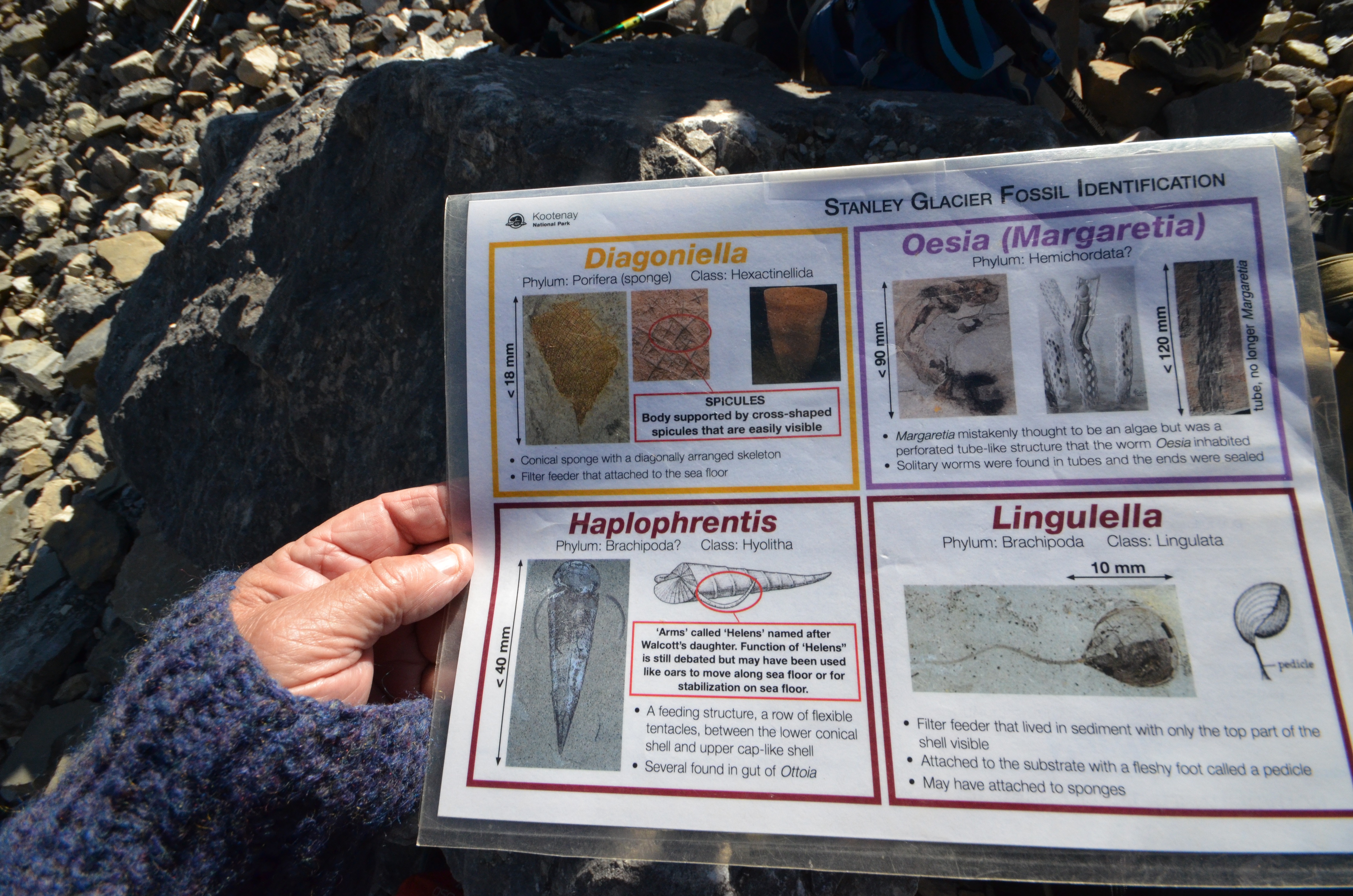

At last we reach the fossil site and we are given last minute instructions along with a plasticized sheet that identifies the most common fossils.

And the search is on.

While you can discover new fossils and maybe even a new species while scouring the Burgess Shale, you cannot keep them. They must be placed reasonably close to where you found them. It doesn’t take me long to cotton on to the fact that rocks that appear to have been deliberately placed on top of larger rocks are very likely candidates for fossils previously unearthed.

Here are just a few of the better examples I found in the 45 minutes allotted for searching.

From a distance this guy almost looks alive.

After the search is over we gather around a lock box from which Laura extracts examples of some of the best fossils found in the Burgess shale.

We also have our lunch which I decline to share with this fall fattened fellow which belies his title as a Least Chipmunk.

We’ve also seen pikas which are much shier and dart under the nearest rock the moment we look their way.

On the walk back, A.J. does a little complaining about his back, but he makes it clear that he’s really glad we came on this hike. By the time we are about a kilometre from the parking lot my knees are also complaining, but I too would put up with more than a little pain to go on this hike. It’s been a great experience for all three generations.

I say goodbye to Alex and A.J. as they head for Calgary and a flight home to Edmonton while I will drive the RV to Redstreak Campground in Radium Hot Springs. The hike has ended about 2:30 so there’s lots of time to get there and I take my time enjoying the beauty of the Kootenay River valley, About twenty kms. (14 miles) from Radium the highway abruptly turns west and climbs up and over a mountain pass before descending through an incredibly narrow opening that is Sinclair canyon.

At the other end of the canyon is the funky mountain town of Radium Hot Springs perched high above the Columbia River valley. Suddenly there are resorts everywhere and every second one seems to have at least one golf course, but I’m not here to golf and head through town and up the steep road to Redstreak campground which will be my home for the next three nights. I get a drive through site with electricity and by the time I’m set up I realize that I’m beat. But not too beat to use my phone as a wifi hotspot for my laptop and watch the first Vikings game of the year while sitting in the tranquility of Kootenay National Park. There are very few people around so I’m not disturbing anyone and just as my phone runs out of juice the game ends with a Vikings win. Ain’t life grand.

Village of Radium Hot Springs

After a good night’s sleep I opted to walk down to town rather than take the RV. It was a lovely late summer morning with no wind and good visibility. The campground sits on ground quite a bit higher than the town and there were some very nice views of the Columbia River valley far below. Radium Hot Springs or just Radium as most people call it, is a village of only 800 people that seems a lot bigger, I think mainly because there are so many businesses catering to tourists. The streets are wide and there is a look of prosperity about the place even though many of the motels that cater to them clearly date back to the 60’s or even 50s. The street lamps have banners on each side and flower baskets hanging from them.

The symbol of Radium is the bighorn sheep and they literally wander the streets unperturbed by the tourists who hop out of their cars to photograph them. This large male was lounging just outside the visitors centre with his female harem close by.

I think the attitude of the people who live in Radium and the Columbia River valley in general, is captured in this sign welcoming visitors to their village.

By now I was more than ready for a hearty breakfast and opted for Fire’D Up Breakfast & Burgers which specializes in breakfast sandwiches and bennies. This chorizo benedict with hash potatoes more than did the trick.

After that I wandered over to the visitor centre which also doubles as an interpretive centre for Kootenay National Park. I needed to recharge my phone that I had run down the night before so whiled away a couple of hours here working on photographs and a few posts. I was amazed at how many bus tours came and went in that time. I was even more amazed at just how little knowledge most of them had of the most common forms of wildlife to be found in the park. Very few were able to identify the Rocky Mountain goat on the left, one even thinking it was a polar bear.

Alison arrived in the rental car that she had taken over from Alex in Calgary and we headed for Radium’s prime attraction, the hot springs.

Radium Hot Springs

The Kootenay area of British Columbia is famous for its many natural hot springs and the route I’ve taken this week is very close to the Hot Springs Circle Route which is a designated scenic drive that takes in seven of them. However, the grandaddy of them all are the springs at Radium which were first made known to the rest of Canada by Sir George Simpson, governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company. He allegedly discovered them in 1841, but as this mural in the aquacourt, as the main building is known, attests, the indigenous people were using them for thousands of years before that.

Originally a private, commercial operation, the springs were expropriated in 1922 and incorporated into Kootenay National Park. From 1949-51 the aquacourt that one sees today was built and the boom years of tourism commenced. Although many improvements have been made over the years, including ones going on during my visit, the original aquacourt remains largely as designed and in 1994 was placed on the Register of Historic Places. Ordinarily there are two pools in operation, one in the rear of the aquacourt which houses the natural hot springs water and a large cool pool that sits in the front. However, for a short while in September which coincided with my visit, the hot pool was closed and its waters diverted into the cool pool which was drained and refilled with the natural spring water.

What makes Radium Hot Springs so popular with visitors is the fact that the waters have very little sulphur content so you don’t get that rotten egg smell associated with many hot springs. Also the temperature, at least for me, was just right. Some hot springs are, not surprisingly, too hot. Here I am enjoying the pleasures of the cool pool turned hot.

With that wave of a hand I say goodbye from Kootenay National Park and hope that I will return again in the not too distant future.