Twyfelfontein – Nambia’s First World Heritage Site

This is my fifth post from a recent trip to Namibia with Canadian travel company Adventures Abroad and will feature the prehistoric rock carvings at Twyfelfontein in the Damaraland region of that country. But first we need to get there from the Skeleton Coast where we have spent the last two days in the very unAfricanlike city of Swakopmund, away from the heat of the Namibian interior. Our journey starts with a drive north along the perpetually foggy Skeleton Coast, past a modern desalination plant which I suspect will become a lot more common method of providing water to African countries as global warming creates more droughts in more places. Just before Henties Bay we spot the remains of one of the many ships that have foundered off this coast over the centuries.

This is the wreck of the Zeila which ran aground in 2008 as it was being towed from Walvis Bay to the infamous boat wrecking yards of Mumbai, India. I guess she had no desire to be pried apart by underpaid and underage children and teenagers working in hellish conditions. Now she provides perfect nesting conditions for three types of cormorants.

Turning northwest just after Henties Bay and saying goodbye to any pavement for the next few days, I watched as the sun reappeared and the temperature began rising by the minute. We were now headed for the region of Namibia known as Damaraland which was once one of the infamous Bantustans or ‘homelands’ established by the apartheid regime that controlled Namibia (then South-West Africa) from after WWI until independence in 1990. There were ten in all in Namibia and they were abolished at independence. Now, quite rightly, all of Namibia is a homeland to all who live there.

Damaraland is, not surprisingly, the ancestral home of the Damara people who inhabit much of north central Namibia. One of guides, Gerhardus Jansen is from Damaraland and during our two days there he pointed out numerous places associated with his growing up in this parched and sun-baked landscape.

Soon, coming into sight was one of Namibia’s most prominent landmarks, the Brandberg, which is the highest mountain in the country at 2,573 metres (8,442 feet). What makes it so unusual is that it is a granitic intrusion that was thrust upwards from an otherwise quite flat landscape so that it can be seen from many miles away in all directions. The name translates from the Afrikaans as Burning Mountain. The Damara name is Dāures which also translates to Burning Mountain. The name comes from the fact that in certain conditions at sunset it does actually look like it is on fire. No doubt because of this characteristic, which it shares with Uluru (Ayer’s Rock) in Australia, it is considered a sacred mountain by the Damara, the Herero and the San (Bushmen) people of this area.

Those up for a rugged walk in the blazing sun make the trek to see the famous White Lady of Brandberg which is a prehistoric rock painting under a rock ledge that has been the subject of much controversy. Now thoroughly discredited, the theory once was that the painting was of Mediterranean origin and proof that white people were the first to inhabit the southern part of Africa. Somehow, the fact that there were hundreds of other rock paintings in the Brandberg area that clearly depicted black and brown skinned people, was overlooked.

Not far after stopping to take the Brandberg picture, Gerhardus slammed on the brakes and made a U-turn. He rushed out of the Land Cruiser and started peering into the grass, while beckoning us to come over quietly. Somehow he had spotted a chameleon on the side of the road. We would never have seen it, but for it breaking cover from the grass and heading for a nearby shrub. Gerhardus was quite excited as it was the first Flap-Necked Chameleon he had ever seen in this area of Namibia. I was even more excited because I’m pretty sure this was the first chameleon of any species I had ever seen in the wild.

It’s not a great photo as he was running like a bugger, but it’s proof that I can check off Flap-Necked Chameleon on the Namibian Wildlife Checklist we were provided with at the start of the tour.

This area of Namibia is known for its many varieties of collectable semi-precious and other brightly coloured stones. Outside the town of Uis we came across a great number of roadside stands selling rocks that had been collected in the Brandberg area. Neither Gerhardus or Perez, our other guide, seemed inclined to stop and I sensed a certain level of disaffection with these roadside rock vendors. Or maybe they were just adhering to Adventures Abroad’s policy of not taking their clients to craft vendors unless expressly asked and no one demanded that we stop. In retrospect I kind of wish we had.

After Uis we turned onto a road that put the Land Cruiser’s suspension to the test. We were now in Desert Elephant country according to this sign blazoned with a rather jaunty looking pachyderm.

Shortly after we stopped for another al fresco lunch under the shade of a camelthorn tree and sure enough there were signs of elephants everywhere. It’s pretty hard to miss elephant shit.

However, our goal today was not to seek out elephants, that will come tomorrow, but rather to get to Twyfelfontein to see the rock carvings, so we didn’t attempt to track down the ones that left evidence of their presence all over the place.

Twyfelfontein

I have no idea how you would find your way to Twyfelfontein on your own. There are no signs indicating that there is a major tourist attraction somewhere out there in the burning sandstone hills. It’s on a road that’s off a tertiary road that’s off a secondary road that’s a hundred kilometres or more from anything that could be called a main road. I’m just glad Gerhardus knew where to look.

I’m a sucker for UNESCO World Heritage Sites and will go a long way out of my way to visit them. At last check I think I’ve been to over 135 sites out of 1,092 so I’ve got lots more to see. However, none of the previous 135 were anywhere near as remote or as hard to get to as Twyfelfontein. It was designated as Namibia’s first World Heritage Site in 2007. In case you are wondering, there’s just one more in Namibia, a place we’ve already been, the Namib Desert, particularly the sand dunes of Sossusvlei.

So what’s the big deal with Twyfelfontein? As I usually do, I’ll let the official UNESCO reason for designation speak for itself:

The rock art forms a coherent, extensive and high quality record of ritual practices relating to hunter-gather communities in this part of southern Africa over at least two millennia and, eloquently reflects the links between ritual and economic practices of hunter-gatherers in terms of the value of reliable water sources in nurturing communities on a seasonal basis.

The first thing to know is that Twyfelfontein means ‘doubtful or occasional spring’. As noted above it is not just the presence of the rock engravings, of which there are over 2,500, but the fact that there was a source of water in an otherwise extremely arid landscape. It was the availability of water that obviously drew the San people to the area to create what is not just a collection of petroglyphs created for art’s sake, but rather a teaching tool and maps of available waterholes. What is amazing to me is that there is no consensus on how old these rock engravings are. UNESCO concedes that they span a period of at least 2,000 years, but other scholars contend they could date as far back as 10,000 years.

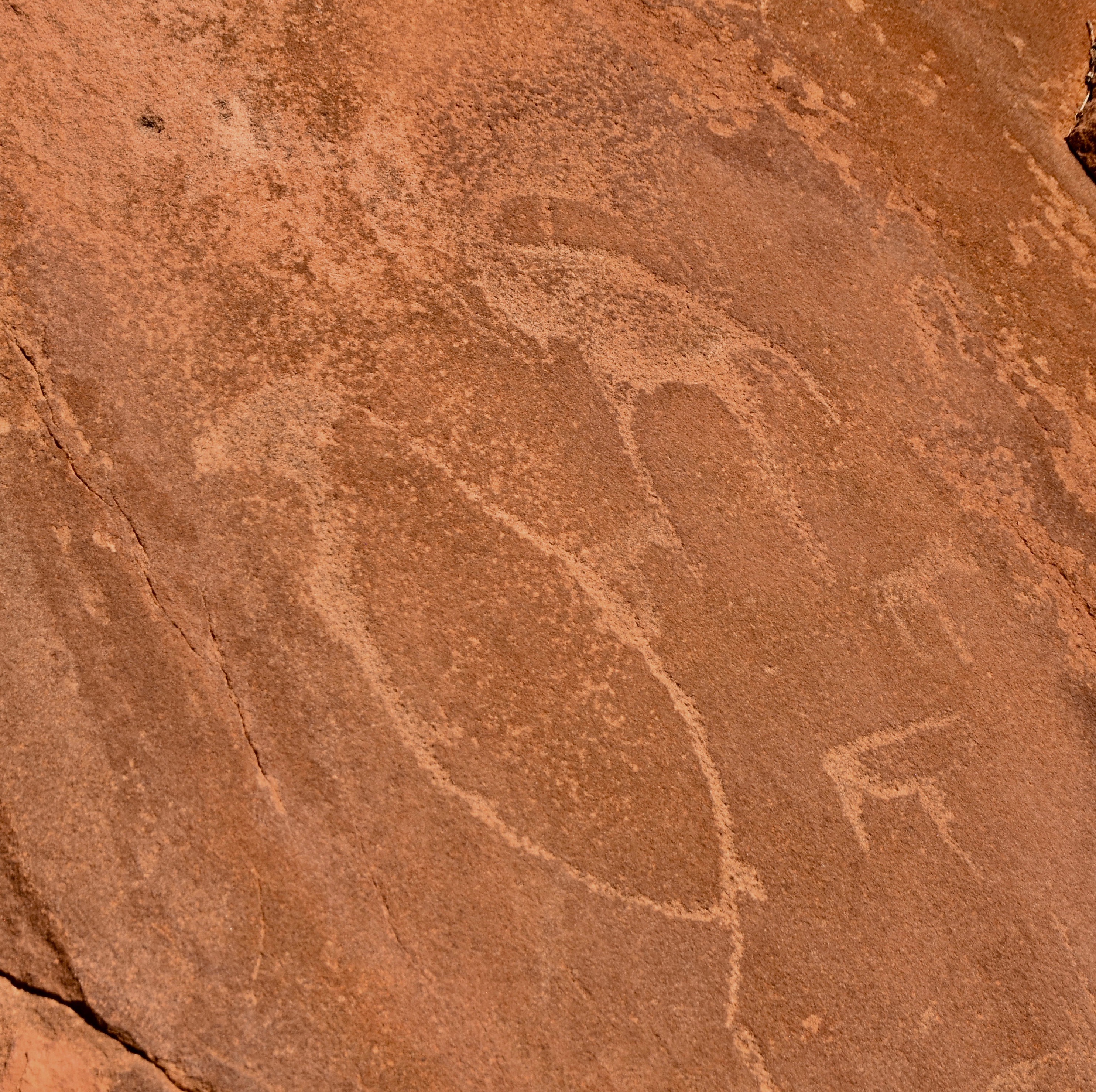

One final point to make is that what you see at Twyfelfontein are petroglyphs and not rock paintings. Both are found throughout the prehistoric record on all continents except Antarctica. The petroglyphs at Twyfelfontein were carved or probably a better term, incised by the use of hard quartz on soft sandstone. With this modest background knowledge let’s visit the site.

After parking the Land Cruisers under a covered shelter there is about a 100 yard walk to the Visitor’s Centre which has information about the creation of the rock engravings and their various meanings. There is also a canteen and a shaded area to sit.

All visitors to Twyfelfontein must be accompanied by a guide and Perez has reserved one for us. The walk to the rock engravings is not long, but the actual viewing areas entail some climbing and scrambling so anyone with mobility issues would be wise to settle for remaining at the Visitor Centre with a cold drink. Several in our group choose that option.

Here is our ragtag group along with our guide heading for Twyfelfontein. The landscape is austere to say the least, but there’s no shortage of red sandstone upon which to carve.

Our first stop is not at any rock engraving, but rather at this abandoned homestead. Apparently eight children were raised in it by a Jewish farmer by the name of Levin who finally gave up the ghost in the 1960’s because the spring was just not reliable any more.

To be sure the Twyfelfontein is still there and occasionally does produce water we are told. That’s it up the side of the hill underneath a protective cover.

At last we arrive at the first rock engraving and learn that is actually a teaching instrument. What at first appears to be just a bunch of random carvings is anything but. If you look closely you will see a number of various animal tracks and even a set of human footprints. Beside the track is an engraving of the animal that would make those tracks. So imagine you are a San youngster and you have come across a set of animal tracks. You would then consult in your mind what you’d learned from studying this petroglyph and decide if the animal was worth pursuing, like a zebra or maybe you should go the other way in the case of say a lion.

This is a closer look.

The rock engravings contain likenesses of a great number of animal species and most are readily identifiable.

Rhinos are still found in Damaraland, but they are very rare and hard to find. Given the great number of rhino engravings at Twyfelfontein they were obviously far more prevalent in the past. Along with giraffes they are probably the most common animal depicted on the petroglyphs.

Speaking of giraffes, here is a very clear example of one along with human footprints – some think these might be the equivalent of an artist’s signature.

Remember I mentioned that some of the petroglyphs are actually maps? Here is one that has been interpreted as a map showing the location of various springs in the area including designations as to whether or not they are permanent or seasonal.

We are 70 kms. (40 miles) from the ocean and that is through some of the most hostile terrain on earth. So what’s the last thing you would expect to see engraved at Twyfelfontein? How about a seal? That’s him in the lower right.

Or how about a penguin? Seriously. This gives us real evidence that the San people had much wider knowledge of the areas outside their traditional territory then was once believed.

Finally here is the Mona Lisa of Twyfelfontein. This petroglyph not only has realistic depictions of over a dozen species, but it also has what at first take is a male lion. However, if you look at his tail you will see it ends in a human hand. This has been interpreted to be a depiction of a San shaman taking on the spirit of a lion.

I know there are some, including one who sits in the White House, who would dismiss the petroglyphs of Twyfelfontein as just a bunch of stupid rock doodles, but they are much more than that. They represent a period of human development before writing was invented and a method of communication that was ingenious and effective for thousands of years. Twyfelfontein may be well off the beaten path, but I do appreciate that Adventures Abroad included it in the Namibia itinerary.

Now we’re off to our next desert lodge Doro Nawas from where we will go in search of the elusive desert elephants of Damaraland. I hope you’ll join us.