Museum of Anatolian Civilizations

I started writing these posts from my last visit to Turkey with Adventures Abroad in what seems like ages ago. Two of the first posts featured the great Istanbul Archaeological Museums. I am now down to the final two posts from this trip and by coincidence or not they will feature two more of Turkey’s great museums. This post will feature some of the most important exhibits from Ankara’s Museum of Anatolian Civilizations and the final one will be on the incomparable Topkapi Palace in Istanbul. So if you’re a fan of history and archaeology please join me on the homeward stretch of what has been another fantastic trip with Adventures Abroad.

Museum of Anatolian Civilizations

The exhibits of the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations are contained in this rather ordinary looking Ottoman structure that was actually a storage building that dates back to the time of Mehmed II the Conqueror. It was part of the complex surrounding Ankara Castle that occupies a very nice position on a wooded hill in the older part of the city. The museum has gone through a number of restorations dating as far back as 1938, with the present layout dating from 1968. In 1997 it won the prestigious European Museum of the Year award, which is kind of strange because it’s not in Europe.

The exhibits cover a vast array of prehistoric and historic eras and civilizations that once were dominant in large parts of Anatolia. The earliest date from from the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age and date back over 11,000 years and then span a period of 9,000 years up to and including the Byzantine era. So without further adieu, let’s view some of the many highlights of the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations.

We start off with Gobleki Tepe, which is now believed to be the oldest prehistoric structure ever found at up to 11,500 years old and a settlement that actually pre-dated the invention of pottery. This is one of the reliefs from the site depicting a number of animals in a manner that shows a level of sophistication that until these were discovered and their true age was determined, no one thought had developed for thousands of years later. It is hard to believe, but the item you are looking at was over 5,000 years old before the first stone was put in place for the Pyramids of Egypt. The fact is that Gobleki Tepe has completely turned archaeology on its head and the implications are only now beginning to sink in. I would love to see this site included on a future Adventures Abroad itinerary.

Another site in Turkey I would also like to see is Çatalhöyük which until Gobleki Tepe was discovered, was a contender for the oldest settlement on the planet. While it is debated if Gobleki Tepe was a site of actual human habitation or simply a sanctuary there is no doubt that Çatalhöyük was occupied from at least 7400 BCE. The site is known for its many decorative wall paintings of which the photo below is one example. This would have been on interior of a private dwelling.

Also from Çatalhöyük is this relief featuring two leopards. Leopards still exist in very limited numbers in Turkey today, but were once found throughout most of Anatolia.

Lastly from Çatalhöyük in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations is this collection of anthropomorphic figures many of which bear a striking likeness to some we saw in the Malta Museum of Archaeology before arriving in Turkey. These hugely obese female figures, often referred to a ‘Venuses’ are found widely throughout early Western civilizations, but I believe the ones in this photo may be the oldest of them all.

We now move on to an important, but often overlooked period of human history, the Chalcolithic or Copper Age which was a transition from the Neolithic or New Stone Age to the Bronze Age. It is considered to be a time when the first city states emerged in places like Crete, the Fertile Crescent, Egypt and of course Turkey with Çatalhöyük and other places becoming legitimate small kingdoms. It was a time when pottery became advanced and many useful household items came into first use, such as those in the photo below.

We now come to what could be considered humankind’s great leap forward, the Bronze Age which lasted from 3300 BCE to about 1200 BCE. Not only did the discovery of how to create bronze from tin and copper change how tools and weapons were made, but it was during this period that writing first emerged. Jewelry and other objects made from gold are now found in great abundance. The Museum of Anatolian Civilizations has a very unique collection from the Bronze Age – the Alaca Höyük bronze standards which were found in what are known as the ‘Princely tombs’ in the ancient settlement of that name. The most famous is the so-called Sun Disk which dates as far back as 2500 BCE. There is no agreement among archaeologists as to what purpose these items were created for, but they represent a substantial advance in the quality of human workmanship.

The small gallery below illustrates the level of that workmanship found in Anatolia at that time.

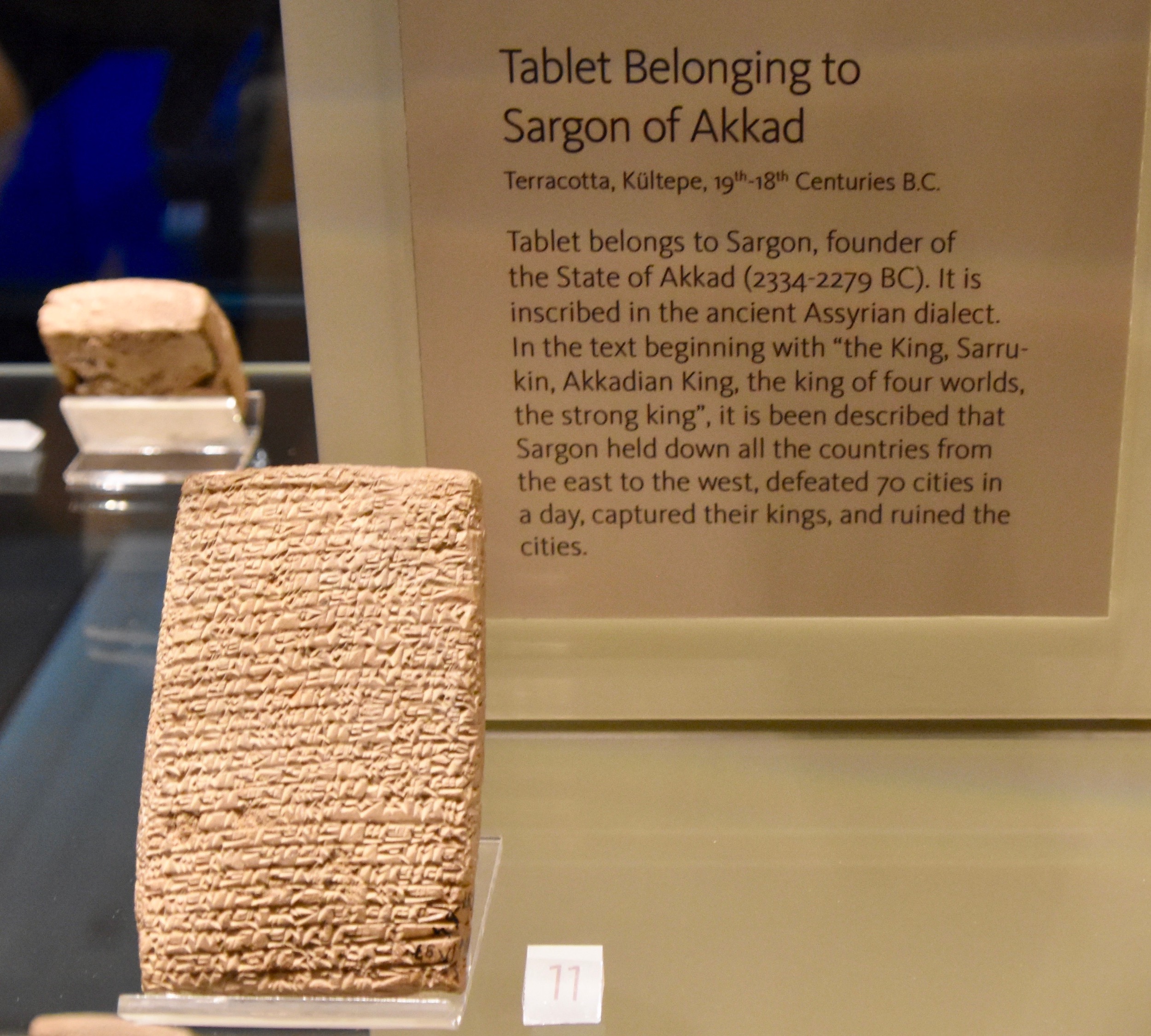

The focus of the next exhibits in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations is not on people from Anatolian, but rather the neighbouring Assyrians who established trading colonies there and so introduced the cuneiform writing that had developed in Mesopotamia. This is a tablet that came from Sargon of Akkad who is credited with being the first person on earth to actually build an empire as he is boasting in this tablet. It’s really hard to get your head around the fact that this little item once may have been handled by a figure so lost in the mists of time as to seem mythical, but he was a real person. BTW his capital of Akkad remains one of the holy grails of archaeology, as yet undiscovered.

This is a photo of some of the Assyrian trade goods found in modern day Turkey.

We now come to the Hittites which many people associate with the earliest civilization in Anatolia, but by now we know they were relative Johnny-come-latelys only springing up in about 1750 BC and remaining on the scene for five or six centuries. However, they were the first to create a true empire within the confines of Anatolia and their influence on subsequent civilizations was immense. There are probably more important Hittite artifacts in the Museum of Anatolian Civilization than from any other period so let’s examine a few starting with these fired ceramic pottery bulls which have a freshness of colour that belies their 3,000+ year pedigree.

Hittites were great carvers of stone reliefs as illustrated by this one featuring three acrobats from Alaca Höyük.

However, if there is one form of art most associated with the Hittites it is surely their sculptural depiction of lions. Lions are such a predominant theme in Hittite art that as we saw in the last post they were chosen to adorn the entranceway to the Ataturk Mausoleum. On this pedestal with their tongues hanging out almost in a panting gesture they reminded me of our two miniature poodles, who often look this way.

This lion is by no means to be confused with a charming pet, but rather the fierceness for which the lion was admired and emulated by the Hittites. It is a fact that lions continued to exist in Anatolia right up to the 19th century when they were finally extirpated as a menace to local herdsmen and their flocks. If only the lion had laid down with the lamb they might still be around.

Sometimes the lion motif was incorporated into the human form as in this chimera like creature.

Around 1200 BCE the Phrygians arrived by sea from the Balkans and overthrew the Hittite Empire. However, the Hittites did survive by moving away from their traditional territory and creating new cities of which Carchemish near the Syrian border was the most notable. This relief on a slab of rock archaeologists call an orthostat shows what the descriptor panel says are three nuns of the goddess Kubaba who was a Syrian deity adopted by these displaced Hittites.

Another orthostat from Carchemish depicts a more martial theme; two warriors on a chariot trampling a fallen foe who has been pierced by an arrow and inexplicably clearly has an erection as he perishes.

We come now to the Phrygian era which lasted from 1200 to 700 BCE. For the first time there are numerous if often contradictory historical references to these peoples by Homer, Herodotus, Strabo and others. The most common belief is that they invaded Anatolia from the Balkans and their first notable king Gordias established the city of Gordion, which is only 80kms. (50 miles) from Ankara as the capital. It was here that centuries after the fall of Phrygia, Alexander the Great sliced through the impossible to untie Gordian knot with his sword and thus according to legend, laid open all of Asia to his conquering army.

This is the goddess Cybele who was the Mother of Gods to the Phrygians – the equivalent of Rhea for the Greeks. She was worshipped under many forms and names throughout Anatolia and beyond. This bust dates from the 6th century BCE which is after Phrygia was a major power and illustrates that the gods often had staying power well beyond the age of the people who first venerated them.

There are countless legends associated with Cybele, many of which you can read by following the link above, but the one most relevant to this visit to the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations is that she was often identified as being the mother of this man.

Yes, King Midas was a real person and not a myth. Certainly the stories about his golden touch and how he came to have the ears of an ass are myths, but he did rule Phrygia from roughly 725 to 675 BCE. His tomb was discovered among a group of royal burials near the city of Gordium and when excavated in the 1950’s proved to be the oldest standing wooden structure in the world. Inside it wooden objects have resisted the forces that normally would have destroyed them in a matter of centuries for over 2,600 years. A number of these are on display at the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations including this intricate stool which has been recreated with the aid of plexiglass.

Also in the tomb were a number of small wooden carvings of which this one depicting a lion attempting to take down a large bull is the most famous.

It was customary to have a funereal feast when the deceased was entombed and after the meal leave the serving bowls and other implements inside the tomb.

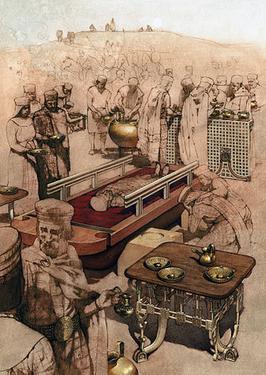

This is a depiction of what that feast might have looked like based upon the objects found in the tomb. Note the the large bronze bowl from which the guests are retrieving their meals.

This is that very bowl, a beautiful object the contents of which have been analyzed and determined to have contained a lamb and lentil stew. This combination of modern methods used on ancient objects really brings the past into focus. Standing here looking at these artifacts I could only shake my head in wonder. King Midas was real! Who knew.

I should add that some scholars think the tomb was that of King Gordias, Midas’ father, but I’ll go with what the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations has to say.

After leaving the Phrygians behind we next come to this large statue of King Mutallu who is described as being a vassal of the Syrian King Sargon II. Other than this description I can find nothing about this guy anywhere on the internet. What is very strange is that the statue is dated anywhere from 1200 to 700 BCE. Since Sargon II reigned from 722 to 705 BCE the statue could hardly be of Mutallu if it predates Sargon’s rule by up to 500 years.

We are now nearing the end of our exploration of the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations as we enter the Greco-Roman era. This bronze statue of Dionysius is outstanding. It was found in the Roman baths in Ankara.

The final object of note is this very unusual Roman tondo bust dug up in Ankara in the 1950’s. Originally believed to be of the Emperor Trajan it is now thought to be a likeness of Ulpius Aelius Pompeianus who presided over the Sacred Games of Ancyra (the Roman name for Ankara) during the reign of Hadrian. Whoever it is, it’s a great example of the realism of Roman portrait sculpture.

With that we conclude our visit to the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations. I hope you have enjoyed it as much as I did. In the final post from this Turkish odyssey we’ll visit one of the great storehouses of antiquities in the world, Topkapi Palace.