Chiricahua National Monument – Geronimo’s Last Stand

This is my ninth post from a trip to Arizona that Alison and I took in November 2024, and the second to feature Arizona’s National Monuments. In the first we visited Walnut Canyon and Montezuma Castle National Monuments. In this post we’ll visit Chiricahua National Monument which is famous for its amazing rock pinnacles and its connection to the Chiricahua Apache tribe, most notably its great resistance leaders Geronimo and Cochise. It promises to be an epic day. I hope you’ll join us.

History of Chiricahua National Monument

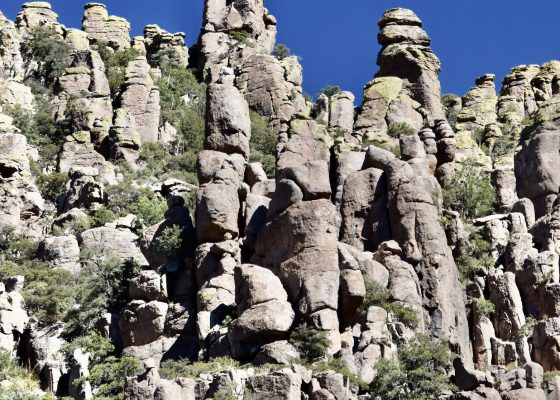

As always, the first time I visit a place I try to do as much advance research as possible in order to not only be prepared for what I am about to experience, but also to make sure I don’t overlook or miss something that might not be obvious to the casual observer. In the case of Chiricahua National Monument the starting point is the National Park Service website. Here I learn that the defining event in terms of the geology and subsequent geomorphology of Chiricahua National Monument was the eruption of the Turkey Creek volcano some 27 million years ago. The volcano spewed out ash over a 1,200 sq. mile (3,100 sq. km.) area in southeast Arizona to a depth of up to 2,000 feet which solidified into rhyolite canyon tuff. Then the forces of nature went to work – ice, rain and wind eroded away the softer material leaving a landscape dotted with rock pinnacles which in Canada we call hoodoos.

This was only half the story. Chiricahua National Monument preserves what is known as a ‘sky island’, a mountain that rises abruptly from the desert floor in isolation from other such mountains and not part of a mountain change per se. This is one of the most unique biogeographical systems in North America where four distinct ecosystems come together. This is the description from the NPS website,

On cooler northern slopes look for ponderosa pine and Douglas fir; both typify the Rocky Mountains. Sunny southern slopes have Apache pine and border pine from Mexico’s Sierra Madre range. Yuccas and sotol from the Chihuahuan Desert coexist with agaves and prickly pear cactus from the Sonoran Desert.

There are over 1,200 species of plants and over 200 bird species, including some that are at there very northern limit such as the elegant trogon and eared quetzal – yes, can actually see a quetzal in United States. Thirteen species of hummingbird have been recorded here as well. The diversity of mammals is perhaps unmatched in the country with 71 recorded species including, believe it or not, an occasional jaguar. It’s also a great place to see, not too close though, many of the rattlesnake species we saw in captivity at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. The black-tailed rattler is apparently quite common.

So you’ve got the fantastic landforms and the incredible flora and fauna of Chiricahua National Monument to draw you there; now let’s add in a little history.

Despite the ecological diversity of Chiricahua National Monument, none of the ecosystems are conducive to agriculture and although artifacts as old as 13,000 years have been found within its boundaries, it seems that there was never anything but transitory visits by Indigenous peoples until about the 15th century. Between 1400 and 1500 the people we know as the Apache migrated into the area from their original home in northwestern Canada where it is believed they were pushed out by more aggressive tribes. The Apache language is of Athabaskan origin and exists as island separated from other Athabaskan languages spoken in Alaska and western Canada by thousands of miles. The word ‘Apache’ is not one used by the them, but rather comes from a Zuni word meaning ‘enemy’ and later adopted by the Spanish and eventually by everyone who is not an Apache.

Unlike most of the other tribes of the American Southwest who were agriculturalists, the Apache were nomadic hunter gatherers and at the time of the arrival of the first Europeans in the 1500’s, roamed over a territory as large as 15 million acres (61,000 sq. km.) in modern day Arizona, New Mexico and northern Mexico. They also had a trait that separated them from the other Indigenous peoples with whom they were neighbours – the warrior culture. Perhaps as a result of being driven from their ancestral home, the Apaches became obsessed with becoming warriors. They underwent a training regimen that culminated with reaching manhood by running nonstop for 48 hours without food or sleep. The stereotype of the Indigenous warrior as a master of weapons, disguise and stealth is largely based on the Apache’s, in effect, the Spartans of the American west.

To the chagrin of their neighbours, part of the warrior culture was raiding, first on other Indigenous tribes, then the Spanish, Mexicans and finally American settlers. From 1700 onward they conducted raids into northern Mexico against the Spanish which lasted until they were bought off with regular rations near the end of the century, almost like the way that European communities had dealt with the Vikings hundreds of years earlier. When Mexico gained independence in 1821 they stopped the tribute and the raids began again. In 1835 Mexico put on bounty on Apache scalps. Then in 1848 the United States gained control of most of the Apache territory after the War with Mexico and matters got even worse.

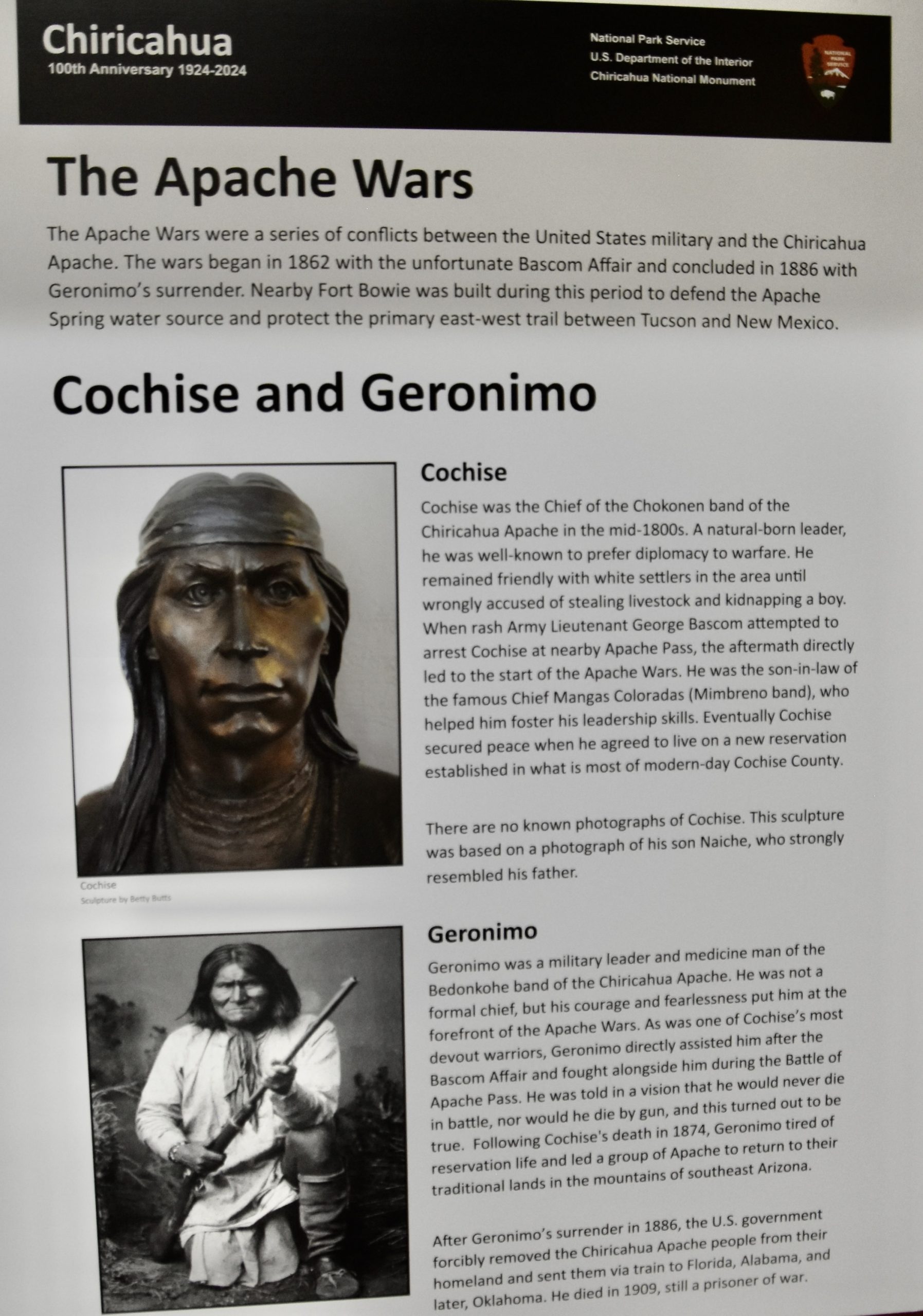

I won’t go into detail about the Apache War of 1861 which was triggered by a false accusation against Chiricahua Apache chief Cochise and led to atrocities on both sides. You can get the details on this link. What followed was the last and longest war in United States history, lasting until 1886. There were two significant periods to the Apache Wars. In the first, Cochise managed to avoid capture for over a dozen years, using the area of present day Chiricahua National Monument as his hiding grounds. In 1872, tired of being on the run, Cochise negotiated a peace treaty that saw the United States grant his people a reservation that covered most of the Chiricahua Apache traditional hunting grounds. This did not sit well with the white settlers who were coming into the area and thought Cochise was being rewarded for his refusal to bow to American authority. Nevertheless, Cochise died of natural causes in 1874 and his body secreted to a burial site not known today, but thought to be somewhere in Chiricahua National Monument.

After Cochise’s death American authorities under pressure from both the settlers and the military looked for a pretence to abolish the Chiricahua reservation and found it after two white men were killed by Apaches. The Chiricahua Apaches were to be removed north to San Carlos Reservation which still exists today as the largest remaining Apache tribal land.

However, not all Apaches were prepared to accept this eviction and relocation including the most famous of them all, Geronimo. Alison I first encountered Geronimo at his birthplace on the Gila River in New Mexico when we visited Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. This is a cairn marking the place of his birth.

Geronimo had been one of Cochise’s best warriors and after his death assumed the leadership even though he was not technically a chief. You can read the rest of the story on this link.

Suffice it to say that in the six years before his surrender in 1886 with only 37 Chiricahua Apaches left at large, Geronimo and his warriors had killed 319 Americans and 682 Mexicans. One of the great ironies of American history is that the final campaign against the Chiricahua Apaches was conducted largely by the Buffalo Soldiers, the newly created all black regiment of the United States Army. One group that had only a few decades gained their freedom, was now instrumental in taking away the freedom from the last of the Indigenous people to actively fight for their own.

BTW his name was not Geronimo, but rather Goyakla. He was given this moniker by the Mexicans who were justly terrified of him – the Mexican army had slain his wife, his mother and a number of his children in an unprovoked massacre in 1851 and he spent the rest of his life getting revenge. Geronimo was known for daring straight on attacks and when the Mexicans saw him coming they would yell ‘Geronimo’ and run like hell. It later morphed into something almost like ‘banzai’, yelled just before an act of seemingly senseless bravery.

After 1886 things quieted down in Chiricahua National Monument. 1888 saw the arrival of Swedish immigrants Neil and Emma Erickson who founded Faraway Ranch which their daughter and her husband turned into a famous dude ranch that operated until 1973. It is still standing and you can tour it as part of your visit. It was built on the site of Camp Bonita which had been established by the Buffalo Soldiers only a few years earlier.

Faraway Ranch advertised itself as the base for exploring The Wonderland of Rocks and this eventually created enough interest in the unique landforms to have the area designated as a national monument by Calvin Coolidge, of all people, in 1924.

The final notable episode to take place at Chiricahua National Monument was the arrival of the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1934. This program started by the Roosevelt government put over 3 million young unemployed men to work building public works during the depths of the Great Depression. Almost all the infrastructure in Chiricahua National Monument including the Vistor Center, the road to Massai Point and the 17 miles of hiking trails were created by the CCC.

Today efforts have been made to convert Chiricahua National Monument into a national park, but with the current administration that seems unlikely to happen.

Alright with that lengthy introduction let’s start exploring!

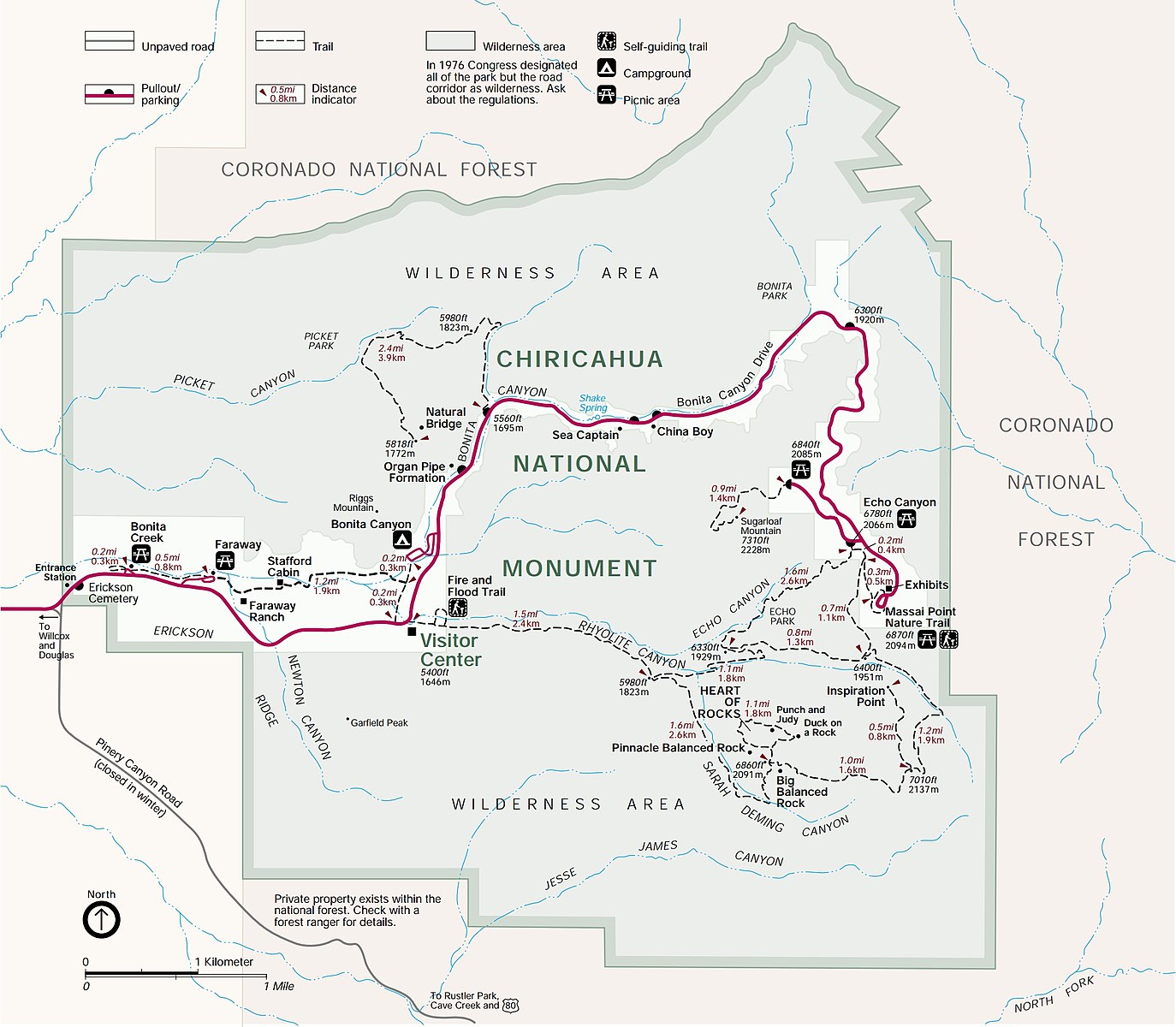

As noted, Chiricahua National Monument is a ‘sky island’ in the remote southeastern section of Arizona. The nearest town is Wilcox which is 36 miles (58 kms.) northwest and there’s dick all between it and the Visitor Centre so you need to get any supplies you need, including gas in Wilcox. If you’re looking to stay in the park there is one small campground with only 23 spaces and these must be reserved in advance. You can do that by following this link. If I were to visit Chiricahua National Monument again I would definitely stay at least one night if not more. This would give enough time time to hike at least some of the trails to see some of the more famous rock formations like Pinnacle Balanced Rock.

Or Duck on a Rock.

Or Natural Bridge.

Add in the opportunity to see some of the rare birds and mammals and the brilliant night sky, unimpeded by any artificial light, and you can see why Chiricahua National Monument is truly a magnificent and unique place to visit.

But alas, Alison and I, like the vast majority of visitors, are only here for a day trip and must satisfy ourselves with what can be seen in a few hours.

Here is a map of Chiricahua National Monument which shows the various hiking trails, all of which are suitable for day hikes and none too long, but some involve serious changes in elevation.

The first stop is the modest Visitor Center where there are exhibits on the flora and fauna, geology and history of the park.

This is where you will learn of the park’s connection to the legendary Apaches, Cochise and Geronimo.

Then it is time to take the scenic drive to Massai Point which rises from 5,400 feet (1646 metres) at the Visitor Center to 6,860 feet (2094 metres) at the top. The road is very narrow, but there are a number of pullouts where you can observe some of the most notable rock formations like the Organ Pipe.

Or one I called Snoopy.

Another pullout gives you a great view of a mountain profile called Cochise Head.

When you reach the parking lot at Massai Point there are a number of hiking options from the very short Massai Nature Trail to one that will take you all the way down to the Visitor Center. No matter what you decide to do, you are going to be blown away by the views from this place. Here is a gallery of photos I took from various trails that started from the parking lot. Double click to open one and double click again to enlarge.

It’s hard to get a perspective on just how big these rock pinnacles are unless you get a person to stand by them as Alison is doing here.

If there is one place on this trip that I wish I had spent more time in, it is definitely Chiricahua National Monument, which was one of the most under the radar natural wonders I have ever visited. This is me with Sugarloaf Mountain in the background. I understand the view from the top is unparalleled, but sadly I’ll probably never see it.

I’m writing this only two days after Trump’s second inauguration amidst vows by many fellow Canadians to never set foot in the United States while he is President. I sympathize with those thoughts, but when I come to places like Chiricahua National Monument I realize that Mother Nature has no politics. These places will always be wonderful and worth visiting and doing so in no way is an endorsement of this, hopefully, passing lunacy.

Next Alison and I will head to one of the most famous towns in the American West, Tombstone with a stop at the Bisbee on the way. Hope you’ll join us there.