Fort Walsh N.H.S.- Important to All Canadians

In my last post I described why Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park is a must visit for anyone interested in a totally unique ecological environment that will completely change your mind about Saskatchewan as a tourist destination. What I didn’t describe were the incredibly important historical events that took place here in the late 1800’s that were critical to forging Canada’s identity as a peaceful country. Those events took place at and around Fort Walsh National Historic Site, deep in the wilds of the West Block of Cypress Hills. Read the last post for a description of how to get to Fort Walsh and what you might see on the way. In this post I will give the history of Fort Walsh followed by a guided building by building tour and then a hike through virgin prairie to the site of the Cypress Hills Massacre.

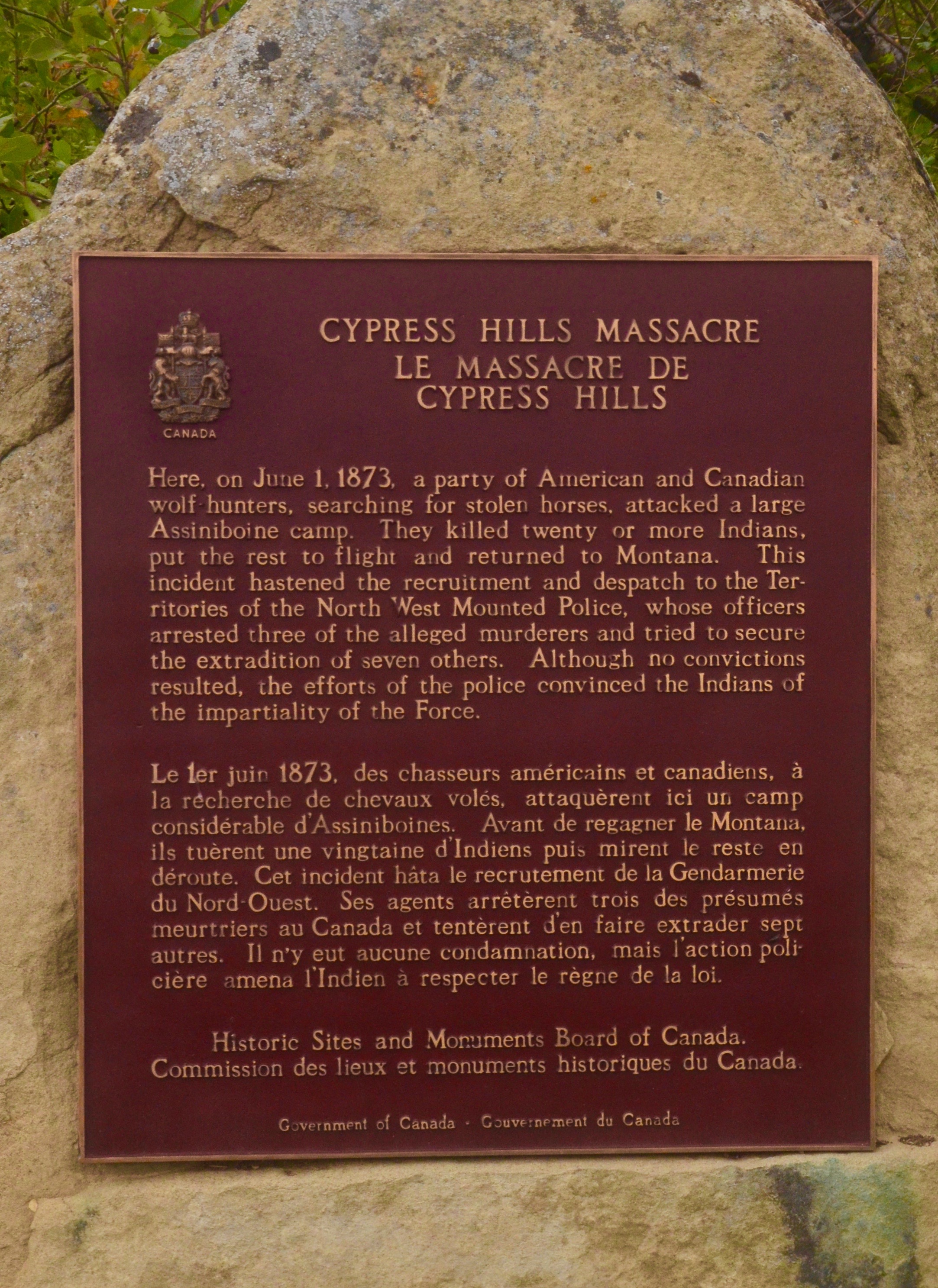

The Cypress Hills Massacre

Massacre is a word with terrible connotations and one we seldom associate with Canadian history. I have to confess to being ignorant of the Cypress Hills Massacre until starting to do research for my visit to Cypress Hills and Fort Walsh. Here’s what happened here on June 1, 1873.

In 1870 Canada was a newly minted nation with just five provinces, Manitoba being the fifth to join in 1870. Manitoba on joining was called the postage stamp province because it was a fraction of the size it is today, comprising the former Red River Settlement along the Red River in what is now the Winnipeg area. Everything else north and west for thousands of miles in each direction was the vast Northwest Territory. While every school kid learns the dates that each province became part of Canada, few are taught that in 1870 the Northwest Territory, purchased from the Hudson Bay Company, also became part of Canada. Have a look at this map and see if you don’t agree that this purchase makes Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase look like a minor real estate deal.

So in the early 1870’s Canada suddenly had control of this vast territory inhabited only by aboriginals. However, it was also exploited by Métis fur traders from the Red River area, professional hunters of buffalo (actually bison), bears, wolves and anything else they could kill for profit (mostly Americans) and a few white traders who dealt not only in necessary supplies, but also whiskey and guns. Whiskey, guns, Americans believing in Manifest Destiny, Métis and aboriginals all searching for ever dwindling bison herds – what could possibly go wrong?

Canada is not a country where the word massacre occurs in our history very often. By contrast if you look up massacres of Indians in the United States in Wikipedia you’ll find over fifty to choose from including such horrific atrocities as Sand Creek and Wounded Knee where the massacres were committed by units led by U.S. Army officers. The Cypress Hills massacre was different in both scale and responsibility. On June 1, 1873 a group of mostly American wolf hunters and fur traders, wrongly believing that an encampment of Assiniboine near two trading posts in the Cypress Hills had stolen a horse, opened fire and killed over twenty men, women and children. Ironically, the only wolf hunter killed was a French Canadian. Knowing they were in foreign territory the perpetrators fled back across the border to safety at Fort Benton, Montana.

When news of the massacre reached Ottawa in August, 1873 it was determined that a much talked about peace force needed to be created asap and sent to take control of the situation in the west, before it deteriorated even more. Thus the North West Mounted Police (NWMP) was created and by November, 1873 recruits were being trained in Manitoba.

Founding of Fort Walsh

One of the principal assignments of the first troop of NWMP to be sent west was to find and bring to justice those responsible for the Cypress Hills massacre. While nobody can pretend that the relationship today between the RCMP and the indigenous community is anything but strained, I think it does behoove underlying Canadian values that back in 1873 it was justice for the slaughtered Assiniboine that was a key factor in the founding of our national police force. It was not the only factor, for sure, but in 1875 James Morrow Walsh arrived at the site of the massacre with his troops and erected a fort nearby, which he modestly named after himself. Actually he was only following the example of Colonel James MacLeod, who, a year earlier founded the first NWMP fort in Alberta and named it Fort MacLeod. Fort Walsh became the headquarters for the NWMP for a period of only eight years, but what an eight years it was!

The first thing Walsh did was shut down the illegal whiskey trade which was wreaking havoc on the indigenous population. The next was to try and determine who was responsible for the massacre, which he did, although he was unable to get the state of Montana to extradite the culprits. The bastards actually got away with it, but not because the people of Canada didn’t try to get them. The next thing Walsh did was to get a number of treaties signed and start the process of assimilating the plains tribes into the European culture which involved essentially becoming farmers. Today a lot of people would call this ‘cultural genocide’, but at the time, Social Darwinism was very much thought to be a real phenomena, and I have no doubt that Walsh was carrying out what the government of the day thought was a reasonable proposition.

Lakota Sioux Refugee Crisis

Today when Canadians hear the words “Refugee Crisis” what comes to mind is the crisis created by the Syrian civil war. Other crises that have brought refugees to Canada have included Somalia, Vietnam and other far away places. One never thinks about refugees actually crossing the Canadian border to escape persecution by the Americans, unless you’re one of the deluded ones who thinks that Vietnam War draft dodgers or Iraq War deserters are ‘refugees’. Yet, from 1876 to 1883, Canada had a true refugee crisis of massive proportions relative to the number of people who crossed the border compared to the number of people already in the area. Superintendent Walsh and his garrison of less than 150 men at Fort Walsh were instrumental in defusing a critical situation that could have triggered an American invasion or another massacre that would dwarf any that had preceded it.

Everybody has heard of the Battle of Little Big Horn or Custer’s Last Stand which took place on June 25-26, 1876 near the Little Bighorn River in eastern Montana. It was the greatest victory any aboriginal groups had ever had over the U.S. Army. 258 American soldiers were killed including the imbecilely over confident General George Custer. Any number of movies have been made about the battle, of which almost all portray the American side of things, with the exception of Little Big Man in which Canadian Chief Dan George played a major role. What almost no one thinks about is “What came next?”

The Americans were not about to let this defeat go unpunished and the Sioux tribes who were the largest indigenous force at the battle knew that. While many later surrendered and were taken to reserves, many led by the famous Lakota holy man Sitting Bull (he was not a warrior chief as is usually supposed) headed across the Canadian border and by 1877 there were 5,000 of his people in the Wood Mountain area of southern Saskatchewan. From the perspective of the Lakota Sioux their traditional hunting grounds had extended well into Canada and they were just moving to another part of their territory where they intended to stay. From the perspective of the Canadian government they were American citizens who had crossed the border illegally and should return, providing they got promises of proper treatment from the American government.

Negotiations to defuse the refugee crisis took place at Fort Walsh where MacLeod was now Commissioner and Walsh Superintendent. They managed to gain the trust and friendship of Sitting Bull by not siding with the Americans and at first, helping out with supplies. When General Terry from the U.S. Army came to Fort Walsh in 1877 to offer a guarantee of safe passage, Sitting Bull didn’t believe him. Here’s an historical vignette of the meeting with aboriginal actor Graham Greene portraying Sitting Bull.

After Sitting Bull’s rejection of the American terms the Canadian government hardened its position. The refugees were not offered any more support and there just were not enough bison and other game left to support their numbers. Walsh ran afoul of his superiors when he redirected supplies intended for his garrison at Fort Walsh to Sitting Bull’s people. Eventually he resigned over what he thought of the treatment Canada was affording the Lakota. Dispirited and starving, Sitting Bull led his people back over the border in 1881 where they were stripped of their weapons and sent to reserves.

While the Lakota refugee crisis didn’t have a particularly happy ending, it could have been a lot worse, but for the efforts of Walsh and his men at Fort Walsh.

By 1882 the force was realizing that the location of Fort Walsh was too remote and too high up to be sustainable – the winters were brutally long and cold. In 1883 it was decommissioned and the garrison moved to a new fort close to current day Maple Creek. However, it was to have one more moment of glory in the 20th century which I’ll discuss later. Now it’s time to visit Fort Walsh.

Fort Walsh – Building by Building

When we arrived at Fort Walsh National Historic Site there was only an RV and a single other car in the parking lot. The interpretive centre was completely encased in plywood, undergoing renovations in order to look its best for the 150th anniversary of Parks Canada in 2017. Inside there are displays recording the history of Fort Walsh and the NWMP as well as a gift shop and café. There are also a couple of large plywood sheets that serve as the guestbook. Neat idea. Here’s Dale signing in after I did.

Outside the interpretive centre sits this impressive sculpture of a Lakota Sioux greeting a NWMP trooper.

The interpretive centre sits on high ground overlooking the Fort Walsh, about half a kilometre away. Since the fort was decommissioned sand dismantled in 1883, you might ask, “Then what’s this I’m looking at?” Recognizing the importance of the site of Fort Walsh it was designated a National Historic Site in 1924 and then in the 1940’s partially rebuilt to serve another purpose for the RCMP which I’ll reveal when we get there.

At the entrance we are met by Ariel, our guide, and a bespectacled NWMP sergeant.

Superintendent’s Building, Fort Walsh

The first building we enter is just inside the gate and was once Superintendent Walsh’s headquarters. From the exterior this, and all other buildings at Fort Walsh look relatively unadorned and primitive. The construction materials were the lodgepole pines found in the Cypress Hills. However, on closer inspection they are quite well built and I am told, rebuilt exactly according to the original plans, so this is what they would have been like in the late 1870’s. Unlike many early Canadian buildings, these have paned glass windows.

Inside the Superintendent’s Building is a scale model of how Fort Walsh looked at its heyday in the early 1880’s. There were far more buildings than have been rebuilt for today’s version of Fort Walsh. Most of what was not rebuilt were the barracks of the enlisted men who, of course, formed the majority of the NWMP at Fort Walsh.

The Superintendent’s Building also has detailed displays relating to the founding of Fort Walsh and the Lakota refugee crisis. It is here that Ariel explains to our group of eight much of what I have written about the history of the place.

Commissioner’s Building

Superintendent Walsh was not the top ranking official at Fort Walsh, that was the Commissioner, the title still used by the head of the RCMP. It has the most posh interior of all the buildings and is very comfortable looking inside. It has wood panelling and there’s a plains grizzly pelt on the wall along with a portrait of Queen Victoria.

The large trunk belonged to Acheson Gosford Irvine who replaced MacLeod as Commissioner in 1880.

I can’t imagine how difficult it must have been to transport something as heavy as this cast iron stove across the prairies on a Red River cart to this remote location. Every occupied building had a cast iron stove, but none as nice as this one with the stag motif.

Everywhere we went inside the gates of Fort Walsh we were accompanied by Nappy, a presumably orphaned calf, as we saw no signs of her mother. She was quite affectionate and on a couple of occasions kicked up her heels and tore around in a circle, just happy to be alive.

Guardhouse & Jail

This tiny building stands opposite the main gate and is where all visitors to Fort Walsh would report upon gaining entry. It also served as the jail. There were three cells, each of which could hold up to four inmates. Terms as long as two years could be served in here, although apparently the longest actually served was about six months. Still, I don’t think Dale would be smiling if he had to share this space with three others for even a day.

The Stables at Fort Walsh

Remember I promised that there was a period when Fort Walsh regained some its former glory? Well it happened in this building, the stables, where the horses used by the RCMP in the musical ride and other duties, were raised for decades. In 1942 the RCMP repurchased the land that Fort Walsh sits on from a rancher who then owned it and established Remount Ranch. Commissioner S.T.Wood was a big believer in equitation skills and had Fort Walsh rebuilt exactly as it looks today with the exception of the palisade which was added by Parks Canada. The idea was to raise a unique type of large, black horse that would come to symbolize the Mounties almost as much as their scarlet tunics. From the late 1940’s until 1968 when the program was moved to Ontario, Fort Walsh served as place where these horses were bred and raised.

All of the horses used in the famous RCMP Musical Ride during this time came from Fort Walsh. However, the most famous horse ever to come out of Fort Walsh was Burmese, who was given as a present to Queen Elizabeth II and immediately became her favourite. She rode Burmese for eighteen years until he died at Windsor Park in 1990. In 2005 the Queen revealed a statue of herself riding Burmese before the Saskatchewan Legislature in Regina.

Carpentry & Blacksmithing Building

The door in the middle leads to the carpenter’s shop where there’s a great collection of the tools that were the mainstay of the carpenter’s profession before the advent of power tools. I wonder how many modern carpenter’s would even know how to use a lot of these.

Next door is the blacksmith’s shop which didn’t look all that different from the few that remain today.

The Armory

The requirement to keep a cache of weapons in the event of trouble meant that Fort Walsh also needed an armorer who could fix broken rifles, muskets and swords.

Fort Walsh also had one rifle barrelled field gun, affectionately called Sweetheart, at least by those not on the receiving end. It was accurate at a range of up to 4,000 yards and is still in use today for ceremonial purposes.

Sergeant’s Barracks

The last and most interesting building inside the fort, for me, was the Sergeant’s Barracks which held most of the regalia we associate most closely with the NWMP including these caps.

Each sergeant got his own space with a bison rug for a bedspread. Looks quite cozy to me.

Many sergeant’s had special stripes to designate their speciality. Here is a ferrier or blacksmith.

The most interesting was this patch. The spurs identified this sergeant as a rough rider or the guy who trained the new recruits from the east how to ride a horse. I wonder if it’s where Saskatchewan’s beloved football team, the Roughriders, takes its name.

That concluded the tour of the buildings inside Fort Walsh, but there was more to see a short distance away where a Métis cabin and trading post have been reconstructed on the same spot as existed even before the fort was built.

Edward McKay established his fur trading post here in 1872. The interior today recreates the various goods that could be bought in exchange for furs. In order from left to right, those are wolf, coyote, badger, red fox, beaver, skunk and muskrat. In the back there was even a wolverine pelt.

That concluded the guided portion of our visit to Fort Walsh, but we had already determined that we were going to walk the 2.5 kms (1½ miles) to the site of the Cypress Hill Massacre. Most people get there by following a road that starts near the interpretive centre, but Ariel advised us that we could make it a loop trail by crossing Battle Creek near the Métis trading station. Since we were already there that’s the option we took. Battle Creek is not much to look at, maybe twenty feet wide at the most, but it is unusual for a Canadian watercourse. It drains into the Missouri River system which in turn drains into the Mississippi River. The water under our feet today, will, in a few weeks or months time, drain into the Gulf of Mexico.

Just over the bridge there was a fork in the trail with the right side headed up a steep hill. Ariel had mentioned that there were a couple of climbs on this side of the stream so we took it. Turns out it was the wrong way, but with a right conclusion. All it did was ascend this hill for at least a couple hundred yards and then ended, but it did so at a pair of Parks Canada’s famous red chairs. These are found in almost every Parks Canada site and are often difficult to find, but once you find them you are always rewarded with a great view. In this case, it was Fort Walsh far, far below. Here’s Dale enjoying the view and the needed rest.

We retraced out steps back to the junction and for the next hour or so enjoyed one of the most pleasant hikes I’ve ever undertaken. It was not difficult although there were the promised ups and downs. What made it so nice was the undulating prairie grasses blowing in the wind interspersed with many types of wildflowers. Overhead there was never a time that a gliding red-tailed hawk or harrier was not in sight. We were so enthralled with this walk that we didn’t want to stop for fear that the spell would be broken and trust me, we were spellbound by this area of Cypress Hills. I didn’t even think to stop and try to capture it on my camera.

Finally we came to the second bridge across Battle Creek and the actual site of the massacre.

I am ending this post, where I started it, with the Cypress Hills Massacre. Even standing on the spot today, it is hard to imagine that day in 1873 when alcohol, racism, greed and suspicion culminated in the cold blooded murder of over twenty souls. I am proud as a Canadian of our response to this event. It could have been better for sure, but it has left a lasting legacy on Canadian history that we all should know more about. That is why Fort Walsh is so important.

Here is a link to a photo gallery of our entire Saskatchewan trip.