Walnut Canyon & Montezuma Castle

A few years ago Alison and I attended the SATW conference in El Paso and after it was over, spent a couple of weeks exploring as many of New Mexico’s national parks and monuments as we could. These included the well known sites of Carlsbad Cavern N.P. and White Sands and the hard to get to, but definitely worth it World Heritage Site of Chaco Canyon. However, as we found out, New Mexico has far more to see than just these A List sites and we really enjoyed getting off the beaten track to visit Bandelier Canyon National Monument, Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument and Tent Rocks, the latter one of the newest in the National Monument system. In the fall of 2024 we returned to the American Southwest, this time to the state of Arizona where we planned to do the same thing we did in New Mexico. We started off with Arizona’s super attraction, Grand Canyon National Park and were duly impressed. Actually that’s an understatement – we were genuinely awed by this beautiful place that truly deserves its reputation as one of great natural wonders of the world. But now we will begin seeking out the lesser know Arizona national parks and monuments, starting with two that are easily visited if your already in the Grand Canyon area. Please join us as we visit Walnut Canyon and Montezuma Castle National Monuments.

Walnut Canyon National Monument

Less than half an hour from downtown Flagstaff, you’ll find Walnut Canyon National Monument which is a world away from the hustle and bustle of that vibrant northern Arizona city. Geologically, Walnut Canyon shares a few things in common with the Grand Canyon although not that much. Whereas the basal rocks at the Grand Canyon are metamorphic and over a billion years old, Walnut Canyon is much younger and is composed of only three distinct layers of sedimentary rock, not the dozens of the Grand Canyon. At the base is Coconino sandstone from 275 million years ago, followed by Toroweap shales and sandstone formed only a couple of million years later and finally topped of with the Kaibab limestone which is also the top layer of the Grand Canyon. The Kaibab limestone is much harder than the other two formations with the result that the bottom layers eroded faster creating a series of natural alcoves that were obvious places to take refuge for the many cultures that once lived here.

Walnut Canyon has an abundance of vegetation and is a much less arid place than the Grand Canyon. The canyon’s modern name comes the Arizona walnut trees that grow as high as fifty feet on the canyon floor and produce an edible oily nut. So comparing this to its northern and much larger neighbour, Walnut Canyon was a much less challenging place to live than the Grand Canyon. The habitat you see today at Walnut Canyon appears to have begun to stabilize about 10,000 years ago which coincides with the oldest traces of human visitation to the area by Paleoindian peoples, in the form of stone projectile points.

The area would seem to have been used only transitorily for the next 9,000 years with little evidence of permanent inhabitation. That changed dramatically at the end of the 11th century with the explosion of Sunset Crater only 15 miles (24 kms.) north of Walnut Canyon. One ordinarily thinks of volcanic eruptions as catastrophic events, e.g. Pompei or Mount St. Helens, but in this case the result was the laying down in Walnut Canyon of a fertile volcanic ash that attracted the first permanent settlers to the area, the Sinagua. Between 1140 and 1250 small numbers of Sinagua lived in cliff dwellings in Walnut Canyon and the remnants of these are the major attraction of the National Monument.

No one knows why the Sinagua people abandoned Walnut Canyon after just over a century of habitation or where they went. Many of Arizona’s northern tribal nations have oral traditions that include Walnut Canyon, so it is surmised that they may have joined with groups that later became identified as Hopi, Navajo, Apache and others.

After the abandonment, there were transitory visits by many different cultures as evidenced by rock carving and pictographs found at various places in the canyon and which also helps explain the oral connection to the area by northern Arizona tribes today. Unfortunately with the coming of a railway to the area in the late 1800s, Walnut Canyon became accessible for the first time to the general public and a period of ‘pot collecting’ i.e. looting, began that stripped the area of almost all archaeological artifacts. Many of the cliff dwellings were dynamited to make it easier to get inside them.

This period of destruction came to an end in 1915 when President Woodrow Wilson declared it a National Monument. Since 1934 it has been administrated by the National Park Service.

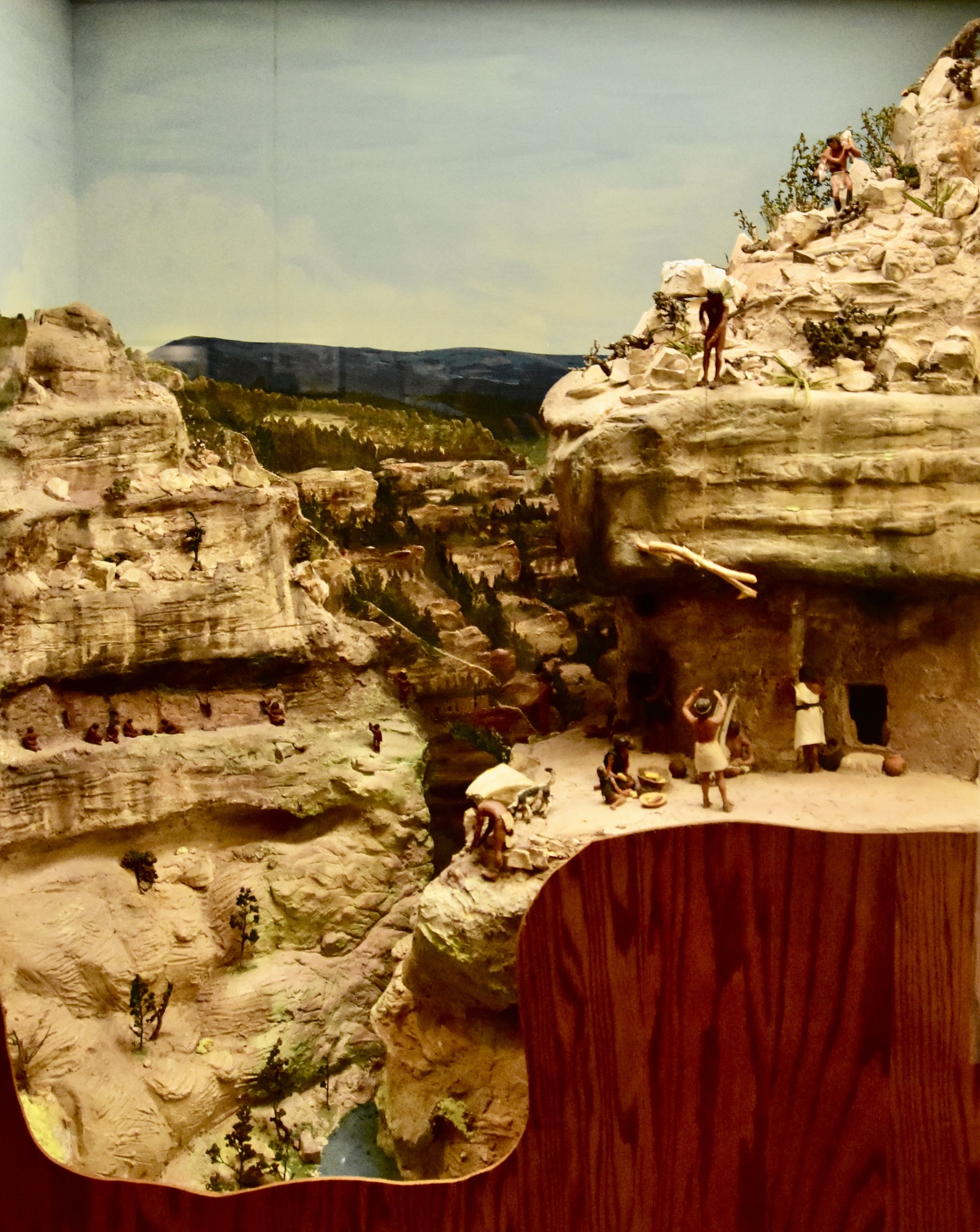

Your visit to Walnut Canyon begins with a three mile drive off Interstate 40 to the Visitor Center where you will find this diorama depicting a Walnut Canyon cliff dwelling from the brief period of permanent inhabitation. There is also short film which will give you a much better understanding of what you are about to see when you descend into the canyon, than if you just tear off like most tourists.

There are only two trails in Walnut Canyon; the Rim Trail goes a short distance along the top and you can get views like the photo below from it.

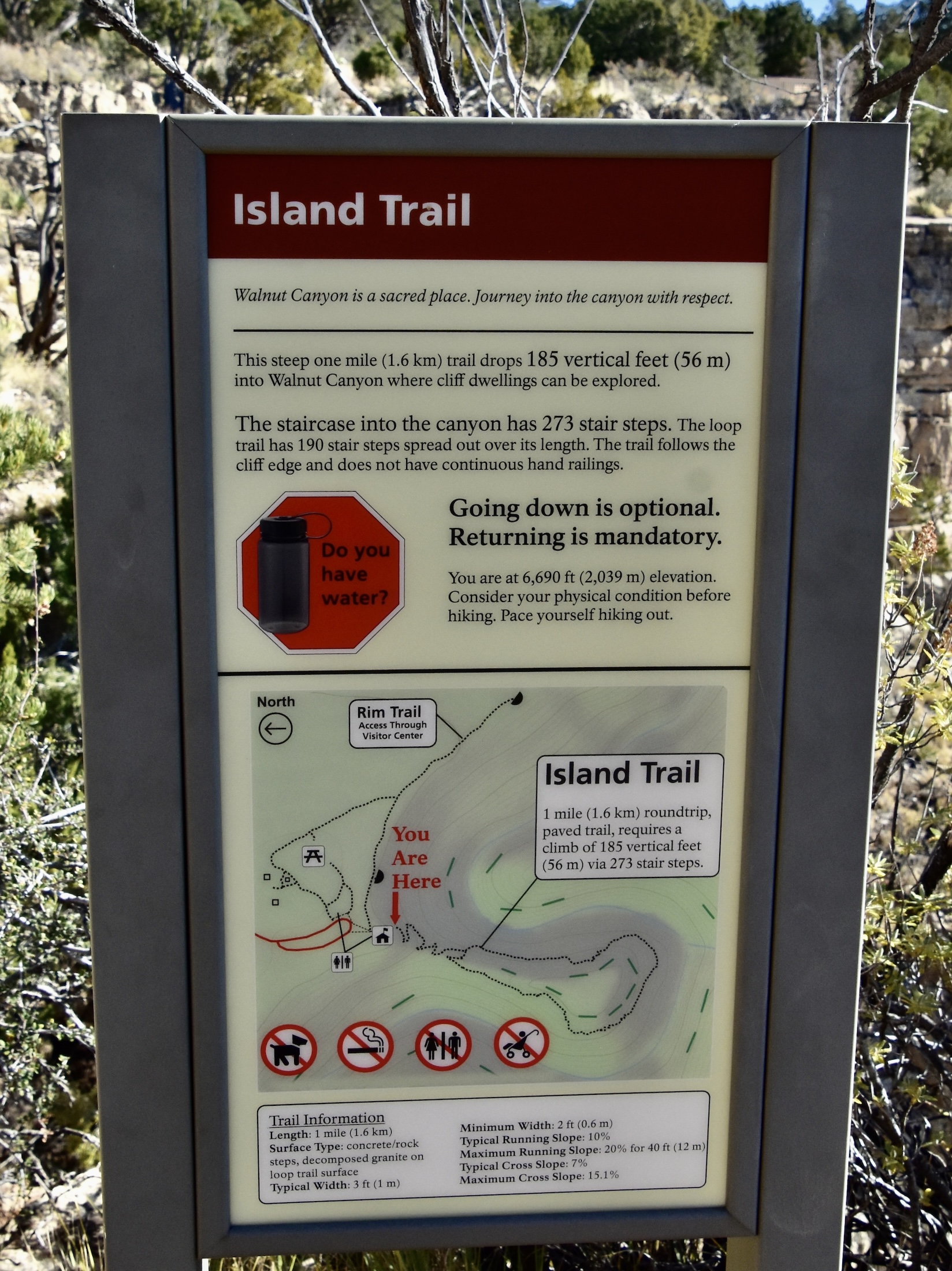

However, the real reason for coming to Walnut Canyon is to see the cliff dwellings close up and for that you need to take the Island Trail which descends some 185 feet (56 metres) down into the canyon. It’s only about a mile long, but the starting elevation is almost 7,000 feet so the air is thin and that climb back up can be exhausting. Also if you are afraid of heights there are a couple of places where there is a very steep drop and no handrails, but in reality this trail should be doable for just about anyone that’s in decent shape.

The trail has numerous interpretive panels that make for good stopping points along the way. On the way down you do get this view of the canyon walls and if you look closely, can see some of the cliff dwellings that are not on the Island Trail.

Once you get to the bottom of the stairs and begin the loop, it is not long before you reach the first of the cliff dwellings. Alison gives a good perspective of just how low the overhanging rocks that form the roof of these dwellings actually were.

There has been a moderate amount of reconstruction to repair the damage caused by the ‘pot collectors’.

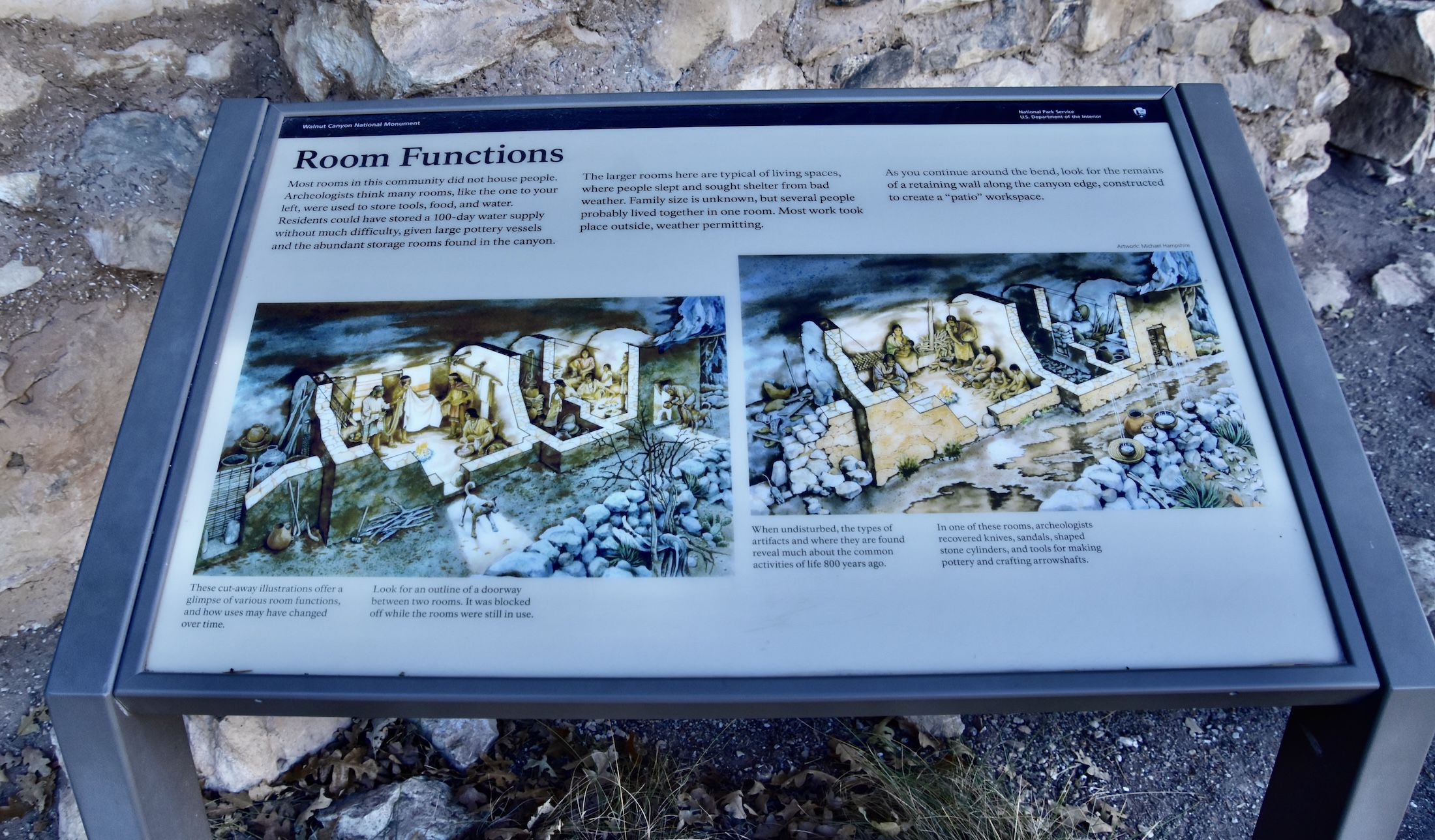

The Interpretive Panels help, but you still need to use your imagination to put yourself in the same position as the people that once called these places home.

The cliff dwellings are not the only reason to make the descent into Walnut Canyon. The limestone formations are photogenic in their own right. There are also three distinct ecosystems on this short trail – Upper Sonoran Desert with cacti and yucca, pinyon and juniper trees on the arid south side and ponderosa pine and Douglas fir on the north side. You can literally see the difference in the change between these three ecosystems in a matter of feet, the transition is that abrupt.

Near the end of the loop you get a good look at the Visitor Center and realize how far you need to climb to get back to the top.

No, Walnut Canyon is not going to usurp the Grand Canyon in terms of grandeur or Mesa Verde in terms of magnificent cliff dwellings, but it is definitely worth the minimal time and effort it takes to explore this area where for just over a century it was home to a small, but thriving community.

Montezuma Castle National Monument

About an hour south of Walnut Canyon is a completely different national monument, but built by the same Sinagua people around the same time as the modest dwellings at Walnut Canyon. In contrast Montezuma Castle is more like a high rise apartment than a single family home and one of the most impressive cliff dwellings in the American Southwest. It’s easy to access and definitely should be on your radar if you have even the slightest interest in the pre-Columbian people who lived in the area before the Europeans arrived.

First of all it should be noted that the fabled Aztec king, Montezuma had nothing to do with the building of this structure. It was a conceit of the Americans who named the place in the 1800s that the Indigenous people of Arizona could not have had the ability to build such an elaborate structure and that it must have been the work of a more ‘sophisticated’ civilization such as the Aztecs. It was, in fact, built around the middle 1100s and occupied until about 1425. A couple of things about it immediately impress one as you make the short walk from the parking lot to the cliff face where Montezuma Castle is embedded inside a large natural indentation in the cliff.

The first is its sheer size, some twenty rooms that once housed up to fifty people. The second is its placement some ninety feet above the Verde River valley floor. Frankly it’s a sight that leaves one wonderstruck and begs the question – “How the hell did they do this?”.

The building is made from stones found at the base of the cliff held together by natural mortar from the Verde River mud. The photo is taken from as close as you can get to it today. Before it was declared a National Monument by Theodore Roosevelt in 1906 it was the subject of frequent looting parties and right up until 1951 people were still going inside. It would take some balls to ascend a ladder some ninety feet to get inside as I can attest from ascending much shorter ones in Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico.

Other than just staring at Montezuma Castle there are a couple of other things of note on the short circular path to and from the parking lot.

This is what is referred to as Castle A which is a little further along the path from Montezuma Castle. It was only ‘discovered’ in 1933 and apparently was once a sizeable cliff dwelling. Because it was not an obvious archaeological site like Montezuma Castle, it was not heavily looted and revealed far more Sinagua artifacts than did the former site.

Another reason to visit Montezuma Castle is to walk among the giant Arizona sycamore trees that grow alongside the riverbank. They are magnificent trees that provided the timber for the roofs of Montezuma Castle and were the source of the Carbon 14 that led to the accurate dating of the site.

I hope you’ve enjoyed our visit to Walnut Canyon and Montezuma Castle as much as Alison and I did. In the next post we’ll continue to explore Arizona with a visit to the Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix.