Hitler Line – Canadians Open the Road to Rome

This is the 12th post on the fall 2016 tour of Canadian WWII sites in Italy put on by the great team at Liberation Tours and the second on what Canadians refer to as the Battle of Liri Valley. In the previous post I described how the Canadians played a pivotal role in breaking the Gustav Line by successfully crossing the Gari River after many previous attempts had failed. From the Gustav Line the Germans dug in at the heavily fortified Hitler Line, which given the name, they were ordered to defend at all costs. Famous last words from Adolph, but ones that inevitably meant furious fighting, often hand to hand, and the consequent heavy casualties on both sides. Please join our group of Canadians, including many sons, daughters and other relatives of the redoubtable soldiers, as we tour the places they fought and died in the Liri Valley.

After visiting the sites along the Gari River we headed up into the hills that flank either side of the Liri Valley. Our first stop was at the small village of Piedimonte San Germano where there is a monument to the Polish soldiers who were so prominent in the capture of the ruins of the abbey at Montecassino. It was also a great vantage point from which to look down on the Liri Valley and get a good idea of why the valley was such an obvious place for the Germans to dig in. If the Allies were able to break through the Hitler Line there was nothing stopping them from marching right up to the doorsteps of Rome by following the course of the Liri and Sacco Rivers.

While most of the others were enjoying their morning espressos I took a short walk around the village and came to this fruit and vegetable stall.

Unlike most North Americans, rural Italians generally still go to a market or small store like this one every day to pick up what they need, and they usually do it by walking, instead of getting in a car and driving miles to the nearest WalMart. No wonder they have way lower rates of obesity and heart disease.

Breaking the The Hitler Line – The Battle of Forme d’Aquino

After the Gustav Line was breached on May 11-12, 1944 British and Indian army units had attempted, without success, to storm the Hitler Line. A set piece battle, Operation Chesterfield, was planned for May 23 and Canadian soldiers were to play the dominant role. Ultimately the Canadians prevailed, but at a horrific cost, with 890 casualties in one day, making it the single worst day of fighting in the entire Italian campaign.

Out next stop is near the Forme d’Aquino River, one of the many small tributaries of the Liri. We park the bus near a small rural crossroads and are joined once again by Italians Roberto Molle and Alessandro Campagna who have taken it upon themselves to make sure that the Canadian efforts in the Liri Valley are properly commemorated. This is kind of ironic, because the sacrifice made by Canadians on May 23, 1944 is barely remembered back in Canada despite the fact the casualty numbers were almost as great as those incurred on D-Day.

We are also joined by this fellow dressed as a Canadian soldier would have been back in 1944. He’s armed with a P.I.A.T. gun (Projector, Infantry Anti-Tank weapon), the notoriously inaccurate British version of the American bazooka.

From the crossroads we make our way down to the bridge that crosses the Forme d’Aquino river. A few sentences back I praised the Italians for their eating habits and now looking down into the stream I damn them for their horrible littering habits. We gave up our lives so you could do this shit? To be fair it seems to be a problem in southern Italy and not the north. The rivers and canals of the Veneto are nothing like this. Anyway, I digress.

This innocuous looking field was the site of the worst of the fighting on May 23. Liberation Tours chief historian Phil Craig makes us relive that horrible day as he describes the utter decimation of three Canadian Regiments – the Princess Patricia Light Infantry (58 killed), the Loyal Edmonton Regiment (50 killed) and the Seaforth Highlanders (52 killed). In addition, the North Irish tankers lost 36 men and an incredible 41 tanks.

I’ve stood on many battlefields around the world from Marathon to Gettysburg to Passchendaele and none have seemed so utterly improbable as Forme d’Aquino. The fact that, almost 75 years ago, this field and woods was drenched with the blood of hundreds of dead and wounded Canadians is simply beyond comprehension. One of the reasons I say that is because, in contrast to the WWI and WWII battle sites in northwest Europe, there is virtually nothing that would let the average passerby have any inkling of the important events that transpired on the Canadian war sites in Italy.

Well that’s not quite accurate, because there is this small monument at the crossroads where we disembarked from the bus. It’s in Italian so any passing Canadian probably would not be aware of its significance. As I write this, the Canadian government is trying to figure out how to spend half a billion dollars commemorating our 150th anniversary. They might start by putting a few bucks aside to better remember the exploits of those who fought and died so we would have a country that would see 150 years.

BTW if you are trying to decipher this monument, the Italians referred to us as the Canadesi and the Germans as the Tedeschi.

We gather round the monument for our first of three groups photos on this memorable day.

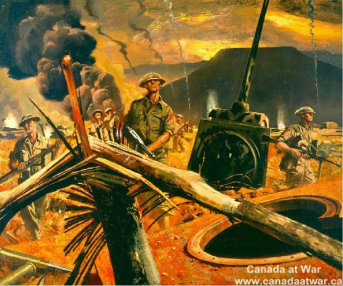

One of the reasons the German defensive lines and in particular the Hitler Line, were so tough to breach was the use of panzerturms by the German forces. These were the turrets and guns from disabled tanks that were then placed in dug out entrenchments and used as a stationary weapon that could pivot 360° with ease. They were hard to see, easy to camouflage and very difficult to take out. Believe it or not there are still remnants of panzerturms to be found in the Liri Valley as Alessandro and Roberto demonstrated as they led us to one in a field not that much different than the one at Forme d’Aquino.

Here is Charles Comfort’s painting of a destroyed panzerturm in the battle to break the Hitler Line.

Breaking the Hitler Line – Pontecorvo

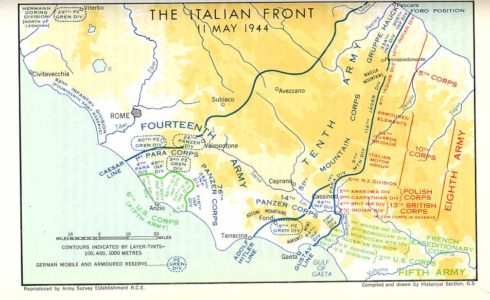

Our next stop was the town of Pontecorvo which dates back to Roman times, but was pretty well destroyed in WWII. From the map below you can see that it sat exactly in the middle of the Hitler Line and after breaking through at Forme d’Aquino it was the Canadian responsibility to take the town, which we did.

This is historian and military author Mark Zuehlke briefing us on the action surrounding the liberation of Pontecorvo. Note the Canadian flag on the artillery piece.

The most interesting story had to do with the ringing of the bell in the Pontecorvo church. Church bell towers were frequently used as places for snipers to use to fire down on unsuspecting troops walking into the town piazza. Pontecorvo was no exception and after ridding the tower of snipers, Canadians rang the bell signifying that the town was freed of the scourge of fascism that had gripped Italy for over twenty years.

Il Borgo

One of the highlights of Liberation Tours, no matter in what country, are the special pre-ordered lunches that help break up the long and often very emotional days of visiting Canadian war sites. John Cannon and Phil Craig go to great lengths to find good restaurants that serve regional cuisine. There are always at least two choices for the main course and lots of locally vinted wine to wash it down. Il Borgo was one of my favourites on the Italian trip. I was greatly looking forward to having lasagna prepared in the country where it originated and boy I was not disappointed. That’s my sister Anne holding up her lasagna. Doesn’t it look great!

While we waited for dessert, New Brunswicker Dave Allison read a passage from Invicta: The Carleton and York Regiment in WWII. This rural New Brunswick regiment played a part in just about every significant Canadian engagement in Italy from Sicily to Ravenna, including the Liri Valley where they were the first regiment to actually break through the Hitler Line.

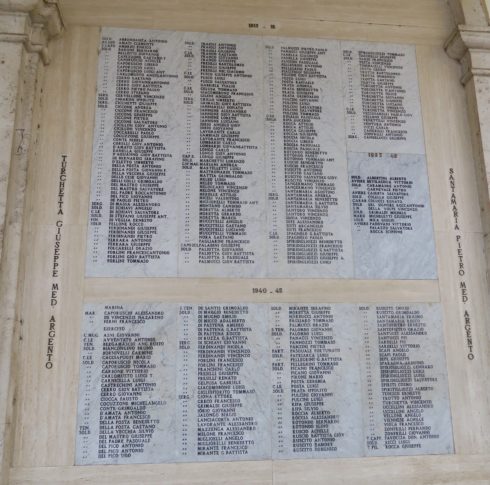

After lunch I had an opportunity to take a short walk around Pontecorvo and came upon this record of war dead in both world wars from the town and surrounding area. Considering that Pontecorvo is a town of 13,200 people, those are truly staggering numbers.

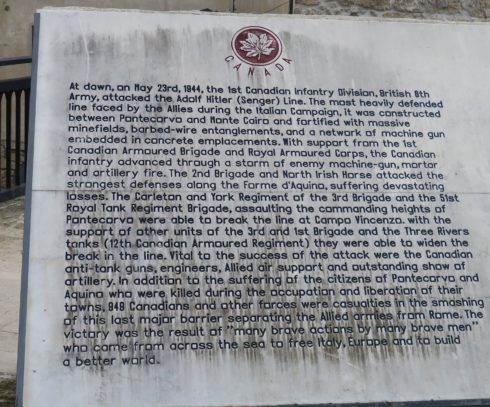

This plaque in Pontecorvo gave the history of the breaking of the Hitler Line and the tremendous losses sustained by the Canadians in doing so, but if you thought the Battle of Liri Valley was over, you’d be mistaken.

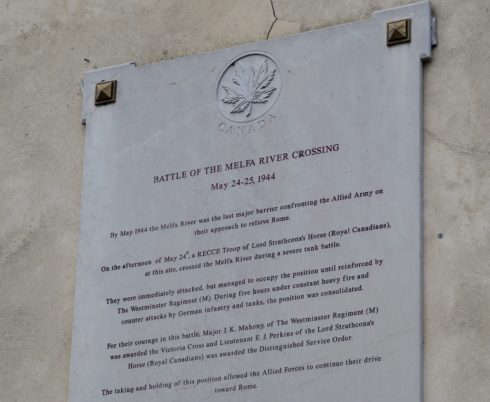

Leaving Pontecorvo, we once more descended to the valley floor and proceeded to go down a series of country lanes, each getting narrower and narrower until there were brambles brushing both sides of the bus. I wondered how we would ever get turned around when we suddenly came to a clearing where there were a few small buildings and one larger one with this plaque attached to the wall.

This obscure, overgrown and figuratively forgotten place was the site of the Battle of Melfa River Crossing which took place near on May 24, 1944, a day after the slaughter at Forme d’Aquino. The Hitler Line had been breached for sure, but there were still river crossings such as that at the Melfa River that needed to be secured. The link provides a detailed account of the battle and why Major J.K. ‘John’ Mahony won a Victoria Cross for his actions on that day.

For the group of us that day, we all listened with rapt attention as Mark Zuehlke, author of The Liri Valley: Canada’s WWII Breakthrough to Rome described Major Mahony’s five hour ordeal as he commanded Canadian troops in capturing and defending the bridgehead against a furious German counterattack. Despite being wounded numerous times and being the target of German snipers he never wavered and ensured that the one of the last obstacles on the way to Rome was secure in Allied hands.

Our group of unusual visitors did not go unnoticed and a little boy of about eight and his big brother came over from a nearby farmyard where his mother was working in the garden. Here is the little guy posed in the middle of this group photo.

In the meantime, Ciro, our trusty driver, had somehow got the bus turned around and we all boarded and headed back to Cassino with our little Italian friend waving us goodbye. It gave me a warm feeling and was a nice way to end our visits to the sites where Canadians helped break the Hitler Line.

So the Hitler Line was broken and the way to Rome wide open, but here’s the thing. Both the Allies and the Germans had declared Rome an ‘open city’ which meant it would not be attacked or defended. In other words it really didn’t need to be liberated in the traditional sense of the meaning. However, that did not stop the glory hound U.S. General Mark Clark from abandoning any effort to encircle the 10th German army once the U.S. army finally broke out from the beachhead at Anzio. Instead of doing what the Russians did at Stalingrad where they successfully encircled and wiped out or captured an entire German army under Field Marshall Paulus that was far larger than the German 10th, he directed his troops to drive for Rome where he could be greeted as the ‘liberator’ of the Eternal City.

This was the same guy who failed to trap the Germans on Sicily, botched the Salerno and Anzio landings and directed the Texan massacre on the Rapido River. With friends like him, who needed enemies? The end result was that, for the Canadians in Italy, the war that might have ended in May 1944, didn’t and the Germans retrenched along the Gothic Line. There was a lot more fighting and dying to come yet.

However, before we move further north to the Gothic Line, my next post will focus on Italian hospitality and a visit to the Cassino Memorial Cemetery where most of the Canadians who died in the Liri Valley are resting. Please join us.