Hagar Qim – Malta’s Major Megalithic Temple

In the last post our Adventures Abroad group visited the Malta National Museum of Archaeology where we saw some of the artefacts found at the various places that make up the UNESCO World Heritage Site The Megalithic Temples of Malta. These included this pendulous breasted woman from the temple of Hagar Qim known as the Venus of Malta.

And this now ascribed asexual being that I might describe as the Lardass of Malta. Please join us as we visit the Temple of Hagar Qim to learn more about the Neolithic period in Malta and the megalithic builders.

The Neolithic Era in Malta

The first thing people might ask is, “What was the Neolithic Era and how did it differ from the Paleolithic Era?” The answer is actually pretty simple – The Neolithic Era or New Stone Age began about 12,000 years years ago and coincided with the commencement of agriculture by human beings. I say human beings because in the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age, which lasted for millions of years, there were more than one species of humanoid on the planet. These included the well known Neanderthals as well as at least seven other lesser known species, but by the start of agriculture it was just us left.

The archaeological record indicates that the first humans arrived in Malta only about 5,900 BC which was well into the Neolithic Era. They came as farmers, bringing with them cereal crops and domesticated pigs, sheep, goats and cattle. Yesterday we saw some of their artefacts found at Ghar Dalam cave which are the oldest in Malta. Unfortunately these first settlers exhausted the soil of the two islands and for about a thousand years it seems there was nobody on Malta. A second wave of people arrived in about 3850 BC from Sicily and this time the settlement was permanent. The difference between the first and second groups was that the first have left no record of permanent structures while the second, until recently, was credited with building the oldest surviving man made structures on the planet. These were the Megalithic temple builders and they were the dominant force in Malta from their arrival until the beginning of the Bronze Age about 2,000 BC. During that time they built many temples of which six, including Hagar Qim are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

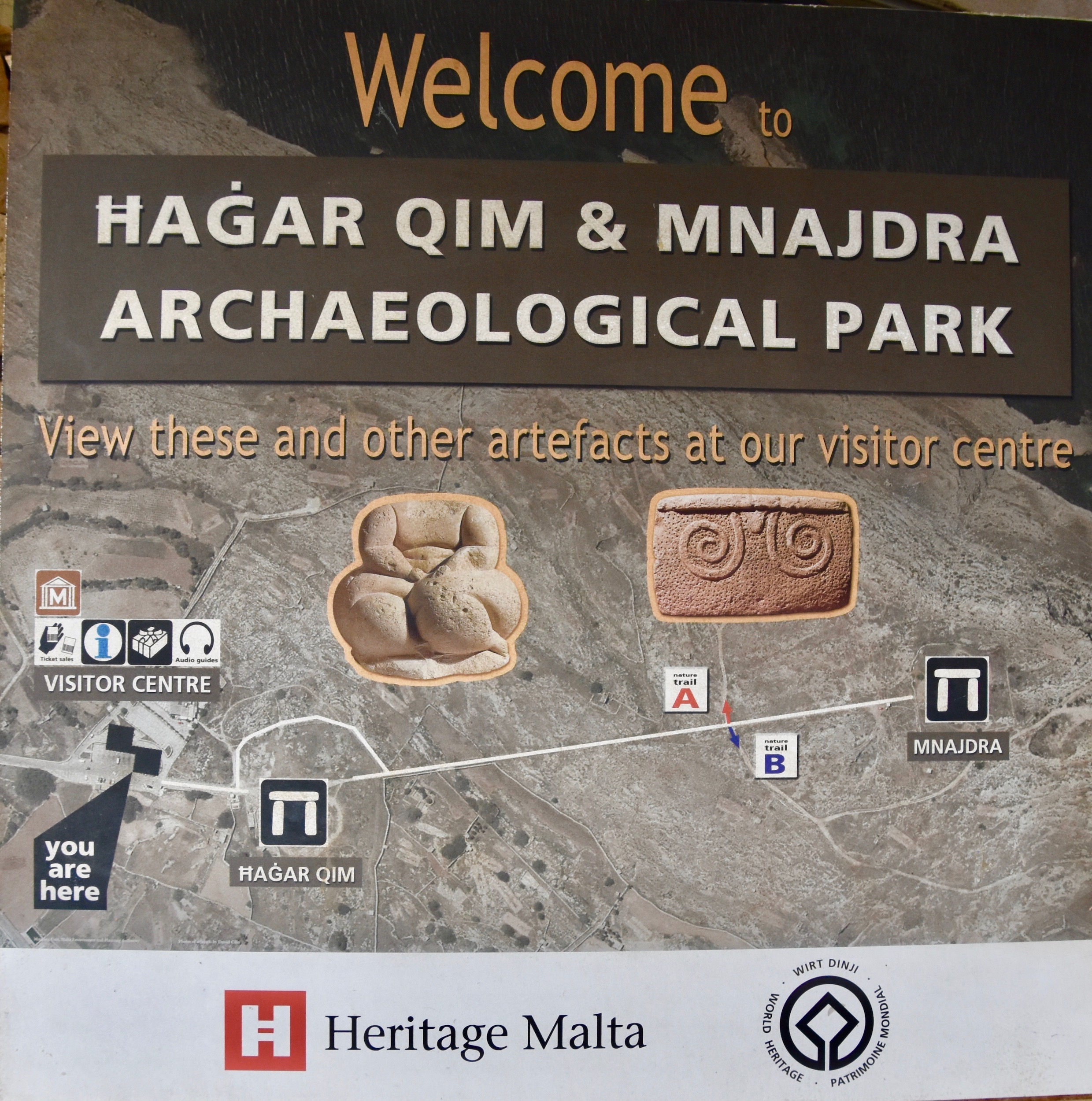

This is a map showing the principal archaeological sites in Malta and Gozo. Hagar Qim is not named, but it is one of the two sites at Mnajdra on the southern coast of Malta.

Visiting Hagar Qim

The great thing about visiting Malta is that it never takes long to get to where you want to go. From our hotel just outside Sliema to Hagar Qim is only about ten kms. (6.2 miles) even though on the map it looks like you’re crossing the entire country, which come to think of it, you are.

We arrive just after the opening hour of 9:00 AM and there’s only a couple of other people here. If there is one upside to Covid it is the decrease in the number of tourists, particularly day tripping cruise ship passengers who can flood a place within minutes of arriving.

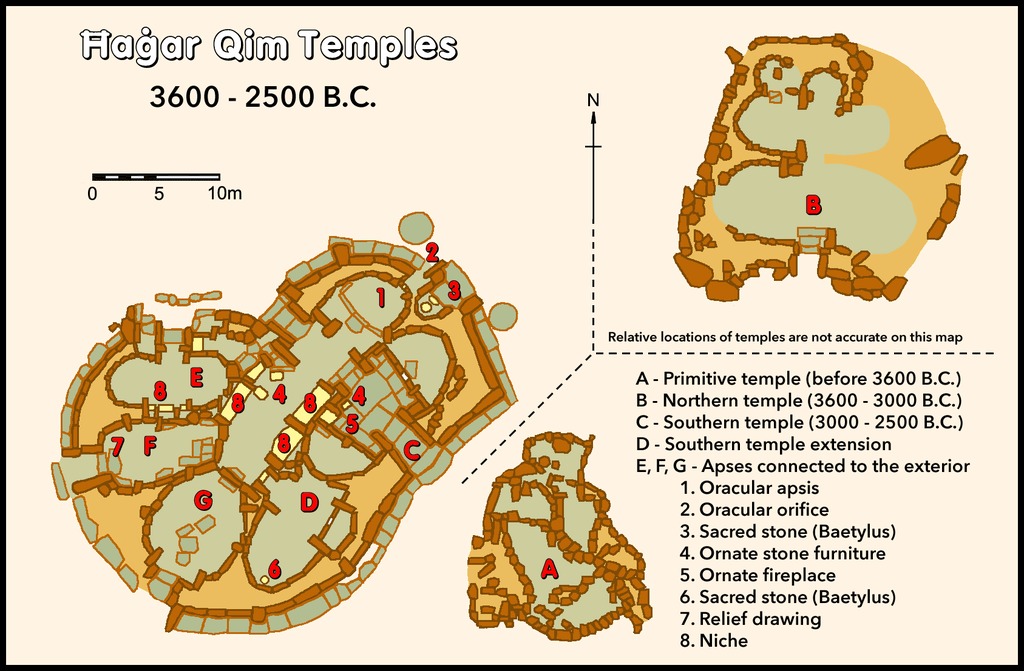

Hagar Qim which simply means ‘standing or worshipping stones’ in Maltese, is actually three structures of which the earliest dates from the oldest period of temple building in Malta, corresponding with the arrival of the new Sicilian colonists in about 3850 BC. By way of comparison that is older than the earliest Egyptian pyramids and up to 1,800 years older than Stonehenge. The second or northern temple dates from 3600 to 3000 BC and the southern temple which is by far the largest, from 3000 to 2500 BC. This schematic shows the three temples and their relative sizes.

The reality is that it is the southern temple that is the main attraction at Hagar Qim as the other two are not recognizable as much more than just a bunch of limestone rocks, at least to my untrained eye.

The visit to Hagar Qim begins at the visitor centre which is on a limestone plateau that overlooks the Mediterranean and the small island of Filfla which hosts a major seabird colony and is the southernmost place in the country of Malta.

Inside the Visitor Centre our local guide Chantelle Shaw pointed out the various highlights we would see on our visit to the primary temple on this scale model.

As you can see it has a main entry way and a series of circular and semi-circular rooms inside that are called apses, the same term used for the part of a church that usually contains the altar and is also semi-circular.

The temple itself is constructed of Globigerina limestone which is what most of the buildings in Malta are still made of. It is relatively soft, full of fossils and about the only available solid rock building material thousands of years ago. The entire country of Malta consists only of sedimentary rock which was laid down in five distinct periods and then upthrust from the ocean floor some hundreds of feet. Of the five layers, three are limestone, one is sandstone and one is hardened mud.

Archaeologists are by no means in agreement as to just how, why and when the Megalithic temples of Malta were built. There is a consensus that the primary temple at Haga Qim was added to in stages, possibly over as much as a thousand year period. With the advent of writing and the end of the pre-history of mankind we have a pretty good idea of the answers to questions like those above for most constructions that post date the Neolithic Era. But when this place was built, there was no written language on Malta and there wouldn’t be for at least another thousand years. There were also no metal tools. No technology really of any sort. So why the temple was built and what the function of each of the rooms and the objects found inside them was, will remain the subject of conjecture. If archaeology teaches us one thing, it is that nothing is written in stone (pun intended). New interpretations, often based on technological advances such as Carbon-14 dating, dendrochronology or DNA sequencing, sometimes completely upend previous thinking about a place or an artefact.

So with this caveat that everything I write about Hagar Qim might turn out to be complete balderdash, let’s begin our exploration. The starting point is a relatively new seven minute audio-visual presentation that explains the history of the temple from the time of its construction to its eventual abandonment and then re-discovery and excavation in the 19th and 20th centuries. After that there’s a few objects to see in the Interpretive Centre including another one of the grossly obese human figures that have been found at Hagar Qim.

This is a perfect example of what I was just writing about – there are as many explanations as to the ‘meaning’ of these type of figures as there are days of the week and no doubt more will be postulated in the future.

Hagar Qim sits on the top of a small rise that our group makes its way up to from the Interpretive Centre. Since 2009 the entire main temple along with the sister site of Mnajdra have been covered by tent like structures intended to slow down the erosion taking place on the soft Globigerina limestone. I have seen these before in places like Cacaxtla, Mexico and while they are visually distracting and tend to reduce the overall grandeur of the sites, it is hard to argue with their purpose.

This is Alison listening to Chantelle at the entrance to Hagar Qim. We have the place entirely to ourselves.

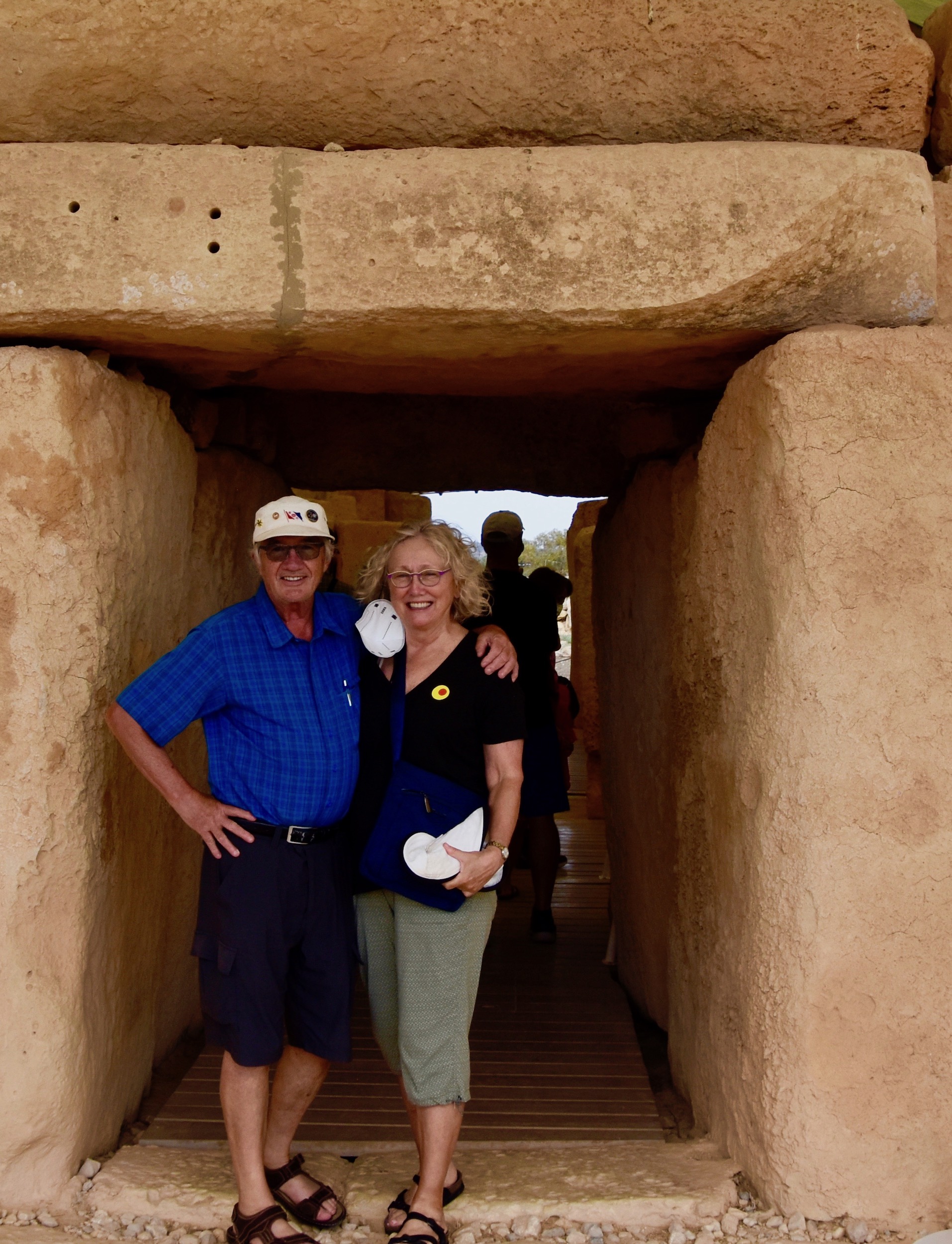

Here is the main entrance to Hagar Qim, in a shape known as a trilithon based on two standing stones capped by a lintel stone. You can look right through and see some of the stones from the earlier temples. It is difficult to comprehend that what you are seeing and are about to enter is one of the oldest know buildings on Earth, parts of which are over 5,000 years old.

Because of the paucity of other tourists, everybody in our group had the chance to get their photo taken at the entrance to Hagar Qim. I could have put my mask in a less conspicuous place.

And here’s what you’ll see immediately inside to your left – a very strange porthole entrance to a small room.

This is what is referred to as the Sculpture Room and is where several artefacts such as this spiral carving were found. This is a copy with the original being in the Malta National Archaeological Museum. It is also where the Venus of Malta and four other statuettes were discovered way back in the 1830’s. Although, adding to the contradictions about this place, I have seen another source that says the Venus wasn’t discovered until the 1950’s.

Another free standing structure inside the oldest part of Hagar Qim is this pedestal or altar which would be one of the oldest ever found, pre-dating the sacrificial altars mentioned in the Old Testament by over a thousand years. There have been examples of animal sacrifice found at Hagar Qim, but the nature of the religion practised here is really one of the areas of conjecture I mentioned earlier.

Archaeologists think Hagar Qim did have a roof as evidenced by these inward curving stones much in the same manner as modern igloos, except built of rock and not ice.

Here is a virtual reconstruction created by Suzanne Psaila, a Maltese woman with a PhD. in archaeo-engineering. It shows how the original temple would have looked 5,000 years ago, before the newer expansions began. Here is a link to the Malta Times article explaining how she came to create it. One cannot miss the similarity to a modern day planetarium.

There are also some interesting places inside the ruins of Hagar Qim where you can see the islet of Filfla clearly through openings in the seaward side of the structure. Was this intentional or accidental? Who knows.

This is a view of the newer parts of Hagar Qim to which public entry is not permitted.

From here you pass through to the open again on the southern side of the temple and near here you will find what I found was the most intriguing mystery about Hagar Qim, the Oracle Hole. This connects to room #1 in the diagram above identified as the oracular apsis.

There is very clearly some type of altar or maybe a type of bench just to the left of the Oracle Hole. One explanation for this is that the person claiming to speak for the oracle would be inside the temple and whisper the answers to someone sitting on the outside, most likely a priest. If that it correct it would make Hagar Qim one of the oldest oracle sites in the world.

On the other hand, is claimed that when the sun rises on the Summer Solstice its rays directly penetrate the Oracle Hole which would make it more of an astronomical function than a religious one.

The most definitive book on the Malta Megalith temples is Malta Prehistory and Temples by the late David Trump (no relation to the former guy) and I have used it as the primary reference for this post. Trump is not sold on the idea of oracles at these sites, but equally does not emphasize the positioning of the temples in relation to observable seasonal or longer astronomical phenomena.

As we leave Hagar Qim, I think this quote from Trump sums up the importance of this and other Maltese Megalith sites.

One of the things we have to appreciate is that their sophisticated architecture is extraordinarily precocious. At the time they were being built, beginning around 3500 BC, no-one else was raising free-standing buildings in stone anywhere else in the world.

The path from the Interpretive Centre to Hagar Qim and back is circular with the option to visit the sister site of Mnajdra which is 500 metres further towards the Mediterranean. Like Hagar Qim it consists of three temples dating from three different construction periods that roughly coincide with those at Hagar Qim. No one knows why two such complexes were built so close together.

Our schedule did not permit us time to visit Mnajdra, but from what I can gather it has many of the same features as Hagar Qim including oracle holes. I’m certainly not going to say that if you’ve seen one Maltese Megalith temple you’ve seen them all, but given our fairly tight itinerary I can understand why we had to take a pass on visiting Mnajdra. Yet another reason to return for another visit to Malta.

One last thing you can observe very well on this walk is the rubble wall agriculture system that is predominant in Malta. This photo shows how fields are partitioned off by dry stone walls that prevent soil erosion. There are remnants of these walls around the Megalith temples that are among the oldest walls in the world.

In our next post we’ll explore another ancient Maltese enigma, the mysterious cart tracks that are found throughout the country. Please join us at Clapham Junction – the one in Malta, not the one in London.